Glacial Geologic Investigations of the Nevado Firura Glacier, Peru

Glacial Geologic Investigations of the Nevado Firura Glacier, Peru

Kurt Radamaker, Gordon Bromley and Louis Fortin

June 15 – July 14, 2005

Recent geoarchaeological investigations in the Andes of southern Peru are providing valuable information about the early human settlement of South America, the possible relationship between the highlands and the coast, and adaptation to the ice age environments of this area. Obsidian (volcanic glass) artifacts found at the 13,000 year-old coastal site Quebrada Jaguay by a UMaine team in the 1990s.

Problems in understanding the initial human settlement of South America are linked to gaps in our knowledge of the glacial geologic history of the Andes during the last deglaciation. Thorough geologic mapping and chronological constraint of the glacial record should enable us to address deficiencies in both areas regarding the timing and extent of regional LGM (Last Glacial Maximum) snowline depression, and thus recent evolution of atmospheric circulation over tropical South America, as well as the climatic nature of the last termination. In addition, the fieldwork will provide valuable insight into the existence of a Younger Dryas readvance in southwestern Peru.

Our field work at the Nevado Firura is also the critical first step in the accurate reconstruction of the local high altitude paleoenvironment. Once we determine the timing and spatial extent of glacial advances and retreats, it will be possible to model other elements of the Terminal Pleistocene and Holocene Andean highland environments, including the distribution and availability of freshwater, biotic communities, and human settlements. Such modelling will be essential for future archaeological research aimed at prehistoric human-ice interactions in the high Andes and other regions. The interdisciplinary expertise and resources of the Climate Change Institute permit us to form the right team for this work, which will contribute to understanding the ways in which climate change affected tropical southern hemisphere glaciation, high elevation Andean environments, and the initial human settlement of the New World.

Our field work at the Nevado Firura is also the critical first step in the accurate reconstruction of the local high altitude paleoenvironment. Once we determine the timing and spatial extent of glacial advances and retreats, it will be possible to model other elements of the Terminal Pleistocene and Holocene Andean highland environments, including the distribution and availability of freshwater, biotic communities, and human settlements. Such modelling will be essential for future archaeological research aimed at prehistoric human-ice interactions in the high Andes and other regions. The interdisciplinary expertise and resources of the Climate Change Institute permit us to form the right team for this work, which will contribute to understanding the ways in which climate change affected tropical southern hemisphere glaciation, high elevation Andean environments, and the initial human settlement of the New World.

15th-16th June Orono to Lima, Peru

Louis writes: We departed Orono just after 5:00AM to carpool down to Portland. Arriving in Portland at 7:15AM, we took the Concord Trailways bus to Boston. We arrived in Boston at 9:40AM where we were dropped off conveniently in front of the American Airlines terminal. After tagging our luggage and waiting in a long line we finally got on the plane and set off for Lima, the capital and largest city of Peru. With a population of 8 million, it has over one-quarter of Peru’s inhabitants. In addition, Lima is extremely large in area, at 2,672 km2 it is the second largest city in the world located in a desert, after Cairo.

Gordon writes: We arrived in Lima this evening (15th June) having received stern warnings to watch for pickpockets and conmen and minus most of our checked baggage. Outside, a huge crowd lays siege to the arrivals hall in the hope that, by grabbing your arm and gesturing towards fliers/taxis/cigarettes, they will earn your business. Even more exhilarating than the initial reception, however, was the 30 minute taxi ride through the smog to reach our hostel, Home Peru. The traffic in Lima is heavy and fast, composed entirely of tiny yellow taxis, called Ticos, and packed smoky buses. And you even have the option of buying pirated DVDs and Sponge Bob paraphernalia from salesmen wandering the roads whilst stopped at traffic lights!

My first impressions of Lima are not entirely complementary. It feels like I’m in a vast sprawl of concrete, under a gloomy grey sky so filled with smog it makes breathing a chore. We’re also sharing our hostel with the backpacker from hell, and his harmonica… On the upside, the food is quite spectacular and we have accomplished a lot during our first full day in Lima (16th June). We made the trip up to the Instituto Nacional de Geografia to purchase aerial photos of our study area, bought our bus tickets, and were reunited with our baggage. The bus we’re catching tonight is the overnight to Arequipa, the last staging post before we get up to Nevado Firura, and the bus ride will take 13 hours in all.

17th – 19th June Arequipa

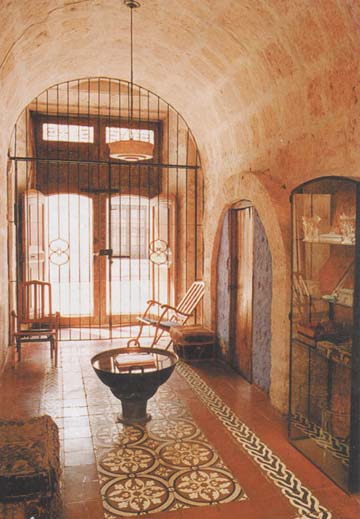

Gordon writes: What a fantastic place! Arequipa lies at 2400 m (7,875 ft) in the shadow of three large volcanoes and is everything Lima is not. The sky is blue, the architecture is beautiful Spanish Colonial, the views are amazing, and the pace of life relaxing. Furthermore, the hotel in which we are staying, La Casa de Melgar (photo), is like a little piece of heaven with its secluded courtyard and sunny gardens. We’re here for three days to sort our gear, make arrangements with our outfitter, and to indulge in the gastronomic paradise that is Peruvian cooking.

All our equipment is being carried into Nevado Firura by mules, so we have had to keep a very close eye on weight. We spent an afternoon in the local markets amassing basic kitchen equipment and much of the food we’d need. They have such a vibrant atmosphere, being full of small Peruvians buying and selling everything from colourful cloth to fruit, nylon bags to chicken feet and pigs’ ears. To keep us on our toes, nothing seems to have a fixed price and so it was rather novel to listen to Kurt haggling with traders in Spanish . All is ready for an early morning departure on the 20th, when we shall be driven to Capilla, a tiny highland village which will be our point of departure for the hike toward Firura.

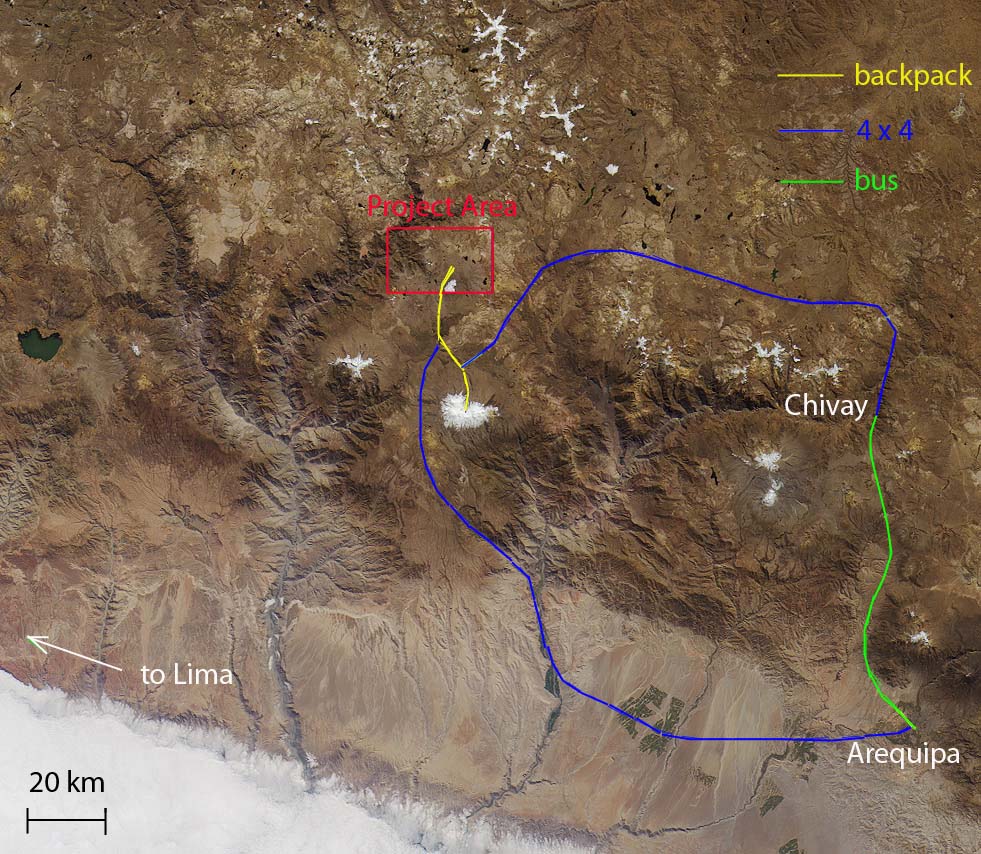

Kurt writes: It’s great to be back in beautiful Arequipa, the “white city,” so named because much of its Spanish architecture is made from a white volcanic rock called sillar. We reunited with my friend Saul Ceron , the owner and operator of Inca Tours Peru (link to Saul’s website), an outfitter and guide agency. Last year we rented equipment from Saul for our trip into the highlands to study the Alca obsidian source. Saul is knowledgeable about the logistical challenges of accessing remote areas of the highlands so it is good to have him on as part of our team this year. He is helping us to organize transportation into and out of our field work site, which will involve a Toyota 4×4, mules, backpacking, and buses.

20th June – Capilla to Nevado Firura

Gordon writes:

20th June: I have been warned repeatedly about eating dodgy food whilst in Peru, so I have been quite paranoid about what I consume. It does get rather tiring, however, having to remove every last bit of salad from a dish for fear of the consequences. No trouble as of yet, though I’m still waiting to see what that tepid papas rellenas I had for breakfast has in store for me! The drive is a long one, from Arequipa to Capilla, and takes us through the lower reaches of the Rio Majes before shuttling us up to 4,300 m. The scenery here is stunning and typically arid, though down in the bottom of the canyon isolated towns are sustained by the river and the green of irrigated land sticks out like a sore thumb.

Up on the plateau it is the snow-capped Nevado Coropuna, the highest volcano in Peru, that dominates the view. Our route took us right underneath it and past textbook landforms of glacial erosion, as well as past some sections of the Inca road. Herds of llama graze this landscape and up close they have very peculiar facial expressions, not to mention red earrings! At this height it gets very cold at night and so I’ve been noticing huge patches of ice lying in the streams and outwash plains. It’s also high enough for us lowlanders to feel a little feeble when moving around, though that should diminish with time. More than anything, it is just a really good feeling to be out of the city and entering our field area.

Capilla is a small, seasonal village in which the herders and their families live during the winter. In summer, when the snow comes, they move to lower elevations. This may seem backwards, but in the Andes the temperature difference between daytime and night time is greater then the temperature difference between winter and summer. We are having highs in the 60s-70s°F and nightly lows around 10°F. The southern hemisphere summer (December to March) is the wet time of the year, which in the highlands means lots of snow on the ground. So highland archaeology and geology is done in the southern hemisphere winter (June to August) when it is the driest time of year there. The Andean pastoral pattern (and the seasonal occupation of high elevation towns) is structured around precipitation since, winter or summer, the temperature will be pretty much the same.

When we pulled in at sunset I remember thinking how desolate it appeared, and deserted, but soon enough a figure appeared from a small house and informed us we could camp in the abandoned churchyard. This was our first night camping and so spirits were high. It was also, however, the first night that I realised how early it gets dark in the tropics. At 6 pm it is both dark and cold, and to top that we each had persistent headaches from the altitude.

21st – 22nd June Capilla to Nevado Firura

21st June:

Ermitano Zuniga, our mule driver, arrived at 8 am prompt this morning with his son Fabian and two mules and two ponies in tow. They seemed to me to be very cynical animals, not as easily pacified by an ear rub as others I’ve known and with generally morose expressions. The driver is very efficient at loading our bags onto the animals, though one particular pony erupted into a bucking fit at the suggestion. Louis, Kurt and I are still feeling the effects of altitude, with headaches that seem to pound behind the temples with unprecedented ferocity. We have a 25 km walk ahead of us which will take us gradually to 5,000 m, passing to the west of Nevado Firura.

22nd June:

We overestimated ourselves yesterday and had to camp some 8 km short of our intended site. We did, however, reach 5,000 m and are currently suffering for it with headaches, lack of appetite, and slowness of movement. This morning we walked to our base camp site after buying a couple of trout from a local fisherman. The site is at 4,900 m and is dusty, windy, and desolate, yet quite beautiful. The now ice-free north side of Nevado Firura faces us, and to the west rise the peaks of Nevado Sapojahuana. We have a lake for water and are out of sight of the footpath which connects the plateau with settlements at lower elevations, making us less likely to be robbed. We’re not working today, just sleeping early and trying to eat something despite the lack of appeal. A valuable climbers’ mantra designed to beat altitude sickness is “climb high, sleep low” so that your red blood cell count can increase as you sleep, but I fear that as we don’t have that option of sleeping low we may suffer the symptoms for longer.

23rd June – 2nd July Field work in the Alturas de Firura

Gordon writes:

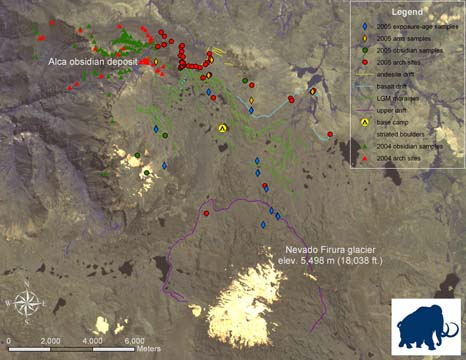

Field work has been progressing rapidly since we arrived on the plateau. After the initial problems with altitude we have now mapped and sampled many tens of square kilometres of moraine and drift, powered by our well-rounded diet of cheese and sugar. Kurt and I have discovered drift units relating to four significant glacial episodes (though it’s too early to comment on likely ages), cored valley-bottoms with the Dutch Corer to retrieve basal peat samples for radiocarbon dating , and have collected over twenty samples of basalt erratics and striated bedrock for exposure-age dating. I pity the poor mule chosen to carry that bag out! Meanwhile, Louis has used a GPS to map the positions and elevations of all the moraine-dammed lakes and many moraines in the area, thus documenting the last recession of the Firura ice front.

I have found the short days rather infuriating. There is only so much ground we can cover before night falls and the temperature plummets to around -12�C. Fortunately, dry Llama pooh makes a magnificent fire and Louis has diligently been collecting sack loads of it. During the day, camp has been a bit inhospitable, plagued by flies if it is calm or by incessant dust storms if windy, so it is always good to get out and mapping early. That wasn’t possible yesterday, unfortunately, for we had foolishly feasted on ‘unsuitable’ salami the night before (it was only two weeks old!) and Louis and I were confined to our tents to suffer the result. On a lighter note, a very bold mouse has joined us and currently resides under the wall.

Louis writes: Camping out in the Andes Mountains was quite an experience. Personally, I have never gone camping before, so living in the middle of nowhere for two weeks was a surreal experience. No longer did I have the city life amenities that I grew up with and took for granted for so long. It was just us three for miles (excluding the alpaca herder and his 300 alpacas). Mornings at first were like a Twilight Zone episode: You would wake up in your confined space of a tent and the minute you start moving you would have these mind wrenching headaches. Next you would stumble out of your tent and instead of seeing Maine and pine trees, you saw these rocky undulating hills and mountains surrounding you, with not a single tree in site. At first it may sound like it was quiet and lonely up there, but it actually wasn’t. During the day a constant wind could be felt almost everywhere you went, and if it wasn’t windy there would be these annoying flies (reminded me of horse flies) that would keep you company. At night when the sun set around 6:00 PM, the temperature dropped drastically. Once everyone was back from field work, supper would be prepared and eaten, after we would head to our tents to sleep. By this time the temperature would have been around 20� Fahrenheit, if not in the teens.

Kurt writes:

After a few days of working through elevation sickness, we are all feeling 100%. We have a great team, with everyone lending somewhat different skills to keep the field work moving forward. Louis is the tech guy – all our mapping equipment and solar power supply is functioning now, and he has been collecting a lot of spatial data that we will eventually incorporate in our Geographic Information System (GIS) to better understand this fascinating landscape. Louis has also been helping me locate and map early preceramic archaeological sites, which abound on the soil surface in a vast area of weathered basalt. Meanwhile, I have been learning a lot about glacial geology while working with Gordon. Every day we are getting stronger and better acclimated to the elevation and the extreme diurnal temperature swings – towards the end of the project we are hiking 20-30 km each day. Camp life has been fun, too. We have been visited by a small desert fox, and one night three runaway alpacas sneak by our camp to parts unknown. Gordon has managed to make us a great breakfast cereal which consists of rice, powdered milk, raisins, and strawberry marmalade. For dinner we usually doctor up ramen noodle soup and eat by the light of our llama dung campfire, dreaming of Pat’s Pizza and watching shooting stars.

3rd – 5th July Field work in the Alturas de Firura

Gordon writes:

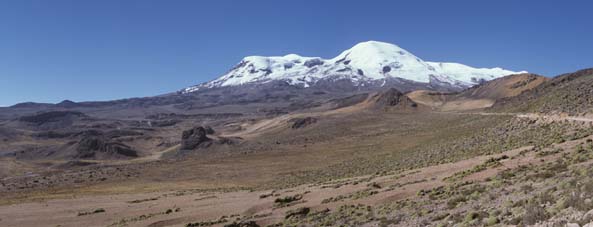

On the 3rd of July we made the trip up Nevado Firura (5,498 m). What aerial photos from 1955 show as a snow capped peak is now a maze of scree and boulders, though a glacier still flows from the southern cirque. From the summit, which is guarded by large blades of snow called penitentes, it is possible to view our study area in its entirety and we took this opportunity to theorise the most probable migratory routes Paleoindian populations might have taken between the coast and the obsidian sources to the north of Nevado Firura. It is also possible from the summit to make out the glacial limits on the southern side of the mountain, an area we were unable to survey for lack of time.

At 8am on the 4th of July, Ermitano, Fabian, and their mules turned up, and we swiftly broke camp, eager to get the 30+ km return trip underway. Being acclimatised this time, we made exceedingly good time across the plateau, following what we now think is part of the Inca road.

Today (5th July) we arrived in Mauca Llacta (which in Quechua means ‘Old Town’), a seasonal village similar to Capilla but larger and distinctly more populous. It is thronged with llamas, alpaca, and children, while barking dogs provide the evening chorus. We’ve been permitted to sleep in a barn next to the medical centre, and have just enjoyed am intense eating binge of biscuits, crackers, and the worst soda in the world . It’s sunny and the nights are warmer down here, and, although I’ve run out of teabags, we’re all very good-humoured.

6th – 10th July Mauca Llacta to Arequipa

6th – 8th July:

Kurt writes: Saul arrived in Mauca Llacta the morning of July 6th and we eagerly set out to climb the Nevado Coropuna, the third highest mountain in Peru at 6,426 m (21,083 feet) elevation. After that bit of relaxation, we made our way via 4×4 across the highlands through the Valle de los Volcanes to the town of Chivay in the Colca Canyon. We went to the Colca to study an unusual labyrinthine terrain, identified by Hal Borns during his visit to the area several years ago. This labyrinthine terrain is known only to occur in one other place – Antarctica.

9th – 10th July:

Gordon writes: We’ve just spent a couple of days in Chivay, which is a bustling little highland town thronged with western tourists. The purpose of this detour was to observe a peculiar area of labyrinth terrain that may have an ancient glacial origin. Within this cacti-infested area of steep knolls and deep troughs we also found walled fields, canals, terraced hillsides, and stone huts, all part of an Inca site called Sol de Sacsayhuama (Quechua for “high ground to attack which provides corpses for vultures”). Strangely enough, not a single tourist (ourselves excepted) was in sight at this amazing place. Now the plan is to make the four hour bus trip back to Arequipa, where we can relax at La Casa de Melgar and celebrate the end of a very successful and well-orchestrated field season.

This project owes its success to many people, both in Peru and at home in Maine. The team would like to thank Dan and Betty Churchill, the Association of Graduate Students, and the UMaine Department of Anthropology and Climate Change Institute for funding, Louis Morin and Bill Congleton of UMaine for GPS equipment, our advisors Dan Sandweiss, Brenda Hall, and Hal Borns and all our friends and colleagues in Peru for their help and hospitality.