Climate Migration in Zimbabwe

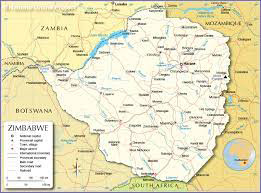

Expedition Location: Harare, Zimbabwe

Expedition Dates: Summer 2023

Field Team Members: Victoria Markiewicz, Dr. Nicholas Micinski

Funding Support: The Robert and Judith Sturgis Family Foundation

Background and Significance:

The eastern region of Zimbabwe is experiencing an increase of intense tropical cyclones that travel through Mozambique from the Indian Ocean. These cyclones cause flooding that destroys livelihoods as well as vital infrastructure and creates patterns of mass migration. The southern part of the country is experiencing severe droughts that are slowly destroying agricultural systems in the region. Communities in impacted regions of Zimbabwe often use migration as a form of adaptation. Temporary migration is often seen in the case of cyclones where communities will move seasonally to avoid the extreme weather. In the case of drought, families will often move permanently, either to an urban area such as Harare or out of the country altogether in a search for better economic opportunities. Annually, a net average of 10,000 migrants leave Zimbabwe each year – 80 percent are going to South Africa.

The number and severity of extreme weather events due to climate change are increasing globally, and sub-Saharan Africa is especially vulnerable. These issues occur because of air temperature warming of 0.8℃ and will continue to worsen as atmospheric CO2 increases. Although the entire African continent only produces 4 percent of global greenhouse gases, African people often face the worst impacts from climate change. For some African communities facing extreme weather, migrating away from impacted regions can seem like the only option for survival. Our research looked at the local implementation of global governance of climate migrants and cooperation between state and non-state actors on the ground to address these issues.

Field Report:

On June 13th, Dr. Micinski and Victoria traveled to Gweru to Midlands State University to meet with their project co-author and give a lecture on climate migration to sociology students. They connected with several professors in the department as well as the dean. On June 15th, they traveled from Gweru to Beitbridge, a city on the border of South Africa. There they met with the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the UN agency that supports Zimbabwean deportees from South Africa, provides emergency assistance, and facilitates transportation to their town of origin. Over 80 percent of Zimbabweans who leave their country immigrate to South Africa. There, some migrants find better job opportunities and can send remittances to struggling family members in Zimbabwe. Unfortunately, many Zimbabweans in South Africa face xenophobic violence. Some struggle to find legal work and others risk deportation if caught without the proper documentation.

On June 16th, Dr. Nicholas Micinski and Victoria Markiewicz organized a climate migration stakeholder meeting in Harare. This acted as a focus group to gather data on climate migration in Zimbabwe as well as serve as a networking event for researchers and activists working on climate migration in Zimbabwe. Representatives from Zimbabwean environmental NGOs were invited, as well as Zimbabwean researchers and professors. The representatives had areas of expertise such as climate justice, migrant labor, conservation, capacity building, youth and women involvement, and research based advocacy. Many participants had personal experience with migration as many Zimbabweans use migration as a form of adaptation to the many concurrent issues facing their country: currency crisis, political oppression, and climate change.

Research Outcomes:

The average Zimbabwean knows far more about migration than about climate change itself. However, those who experience climate disasters in Zimbabwe, such as droughts, floods, and cyclones, understand the concept intimately. Some communities temporarily move in advance of a rainy season or a dry season with the expectation of drought, flood, or cyclone. Long term migration happens both from rural to urban areas and from urban to rural areas as people seek better living conditions within their country.

Zimbabwe was unprepared for Cyclone Idai in 2019 – a massive cyclone that caused widespread suffering, death, homelessness, and loss of livelihood. International organizations provided temporary humanitarian assistance to victims of Cyclone Idai but did not stay long enough to provide continued assistance. The government did not have a long term plan for how to deal with the victims and focused only on keeping victims alive and moving them away from the area of disaster. The Zimbabwean government’s disaster response committees (run by the state military) were viewed as corrupt and inadequate for dealing with problems of this scale.

Victims of natural disasters need more than survival, they need quality of life, livelihood assistance, and psychosocial support. After Cyclone Idai, the government hindered the distribution of international aid by closing off access to the disaster areas. The Zimbabwean government often uses climate disasters to fundraise international aid but is often not distributed to the victims of climate events. This blatant corruption caused some international organizations to withhold emergency aid altogether. After four years, Zimbabweans are still suffering from Cyclone Idai, despite the international aid that was provided. Aid has also been politicized: communities that support the ruling party are more likely to receive help from the government, which leaves opposition areas vulnerable.

There was an overall lack of coordination after the disaster from all groups, including international organizations, government ministries, and civil society. Questions remain such as: Who should be in charge of coordinating disaster response? How can Zimbabwean citizens hold corrupt government officials accountable? Will Zimbabwe be able to respond better during the next climate disaster?

Many Zimbabweans believe that they cannot fully rely on the international community to help solve climate migration problems. The solution may be to involve communities in both knowledge creation and knowledge dissemination around climate migration issues. Indigenous knowledge should also be utilized. Long term solutions are also needed to help communities rebuild livelihoods so that they are not forced to migrate and risk xenophobic violence abroad.