El Niño, Power, and Resilience in the Lambayeque Valley: Building Connections for Future Research

Expedition Field Team Members:

Elizabeth Leclerc1,2*, Heather Landázuri1,2*, Daniel Sandweiss1,2, Oswaldo Chozo Capuñay3, Alberto López

1Climate Change Institute, University of Maine

2Department of Anthropology, University of Maine

3Túcume Archaeological Site and Museum

*Student grantees

Field Expedition Location: Lambayeque Valley, Peru

Expedition Dates: June 2022

Funding Support: The Robert & Judith Sturgis Family Foundation

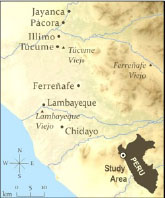

In June of 2022, CCI students Elizabeth Leclerc and Heather Landázuri conducted a ten-day field visit of the Lambayeque Valley, Peru, with Institute faculty member Dr. Daniel Sandweiss and photographer Alberto López. The purpose of the visit was three-fold: 1) to become acquainted with local communities through a valley reconnaissance; 2) assess the potential for a medium-term research project that will become the core of Leclerc’s dissertation work; and 3) to obtain ground truth on the locations of the pre-1578 AD town sites in support of our ongoing spatial analysis of the testimonies. The team visited seven communities in the valley, including the regional capital of Chiclayo (Figure 1).

Each of these communities was established prior to the AD 1578 El Niño as a reducción, or resettlement village populated through the forced removal of Indigenous people from their traditional villages, and each is represented in the historic testimonies of the El Niño event.

In each community, the team visited and photographed important public spaces, such as Plazas de Armas (central squares), churches, municipal buildings, historic buildings, parks, and cultural institutions (Figure 2). Peruvian team member Oswaldo Chozo Capuñay accompanied us for two days during which he showed us the Túcume Viejo (Old Túcume) town site, the archaeological site of Túcume where he works, the Bosque de Poma bio-cultural park, and agricultural and irrigation infrastructure of the Túcume area that were affected by a devastating El Niño in 2017.

The team also met with leading archaeologists working in the Lambayeque Valley, including Dr. Carlos Wester, director of the Brüning National Archaeological Museum in the town of Lambayeque, and Dr. Carlos Elera, director of the National Museum of Sicán in Ferreñafe. Dr. Elera accompanied the team on an excursion into the Pampa de Chaparrí, an area of well-preserved archaeological sites and relict agricultural fields used prior to Spanish colonization, including the former Indigenous village of Ferreñafe Viejo (Old Ferreñafe).

Findings and Signifance:

During the field visit, the team made important connections with local archaeologists and community members and collected data on seven towns in the Lambayeque Valley. Through the reconnaissance of historic architecture, historical research, and conversations with locals, we confirmed the historic locations for five of the seven towns at the time of AD 1578 El Niño (Chiclayo, Lambayeque, Ferreñafe, Túcume, and Jayanca). The towns of Pacora and Íllimo were heavily damaged during the AD 1578 event and, like other communities, were relocated in the following years. However, unlike the other communities we did not locate evidence of the historic townsites during the reconnaissance.

Through the connections made and data collected during the field visit, the team identified several possibilities for future research. There is potential for intact archaeological deposits at the historic townsites of Túcume and Jayanca that may provide evidence of lifeways before, during, and possibly immediately after the AD 1578 event. In addition, it seems that Indigenous habitation at the former villages of Ferreñafe Viejo and Lambayeque Viejo may have continued at least in part until the El Niño, and intact archaeological deposits are likely at least at the former (the team did not visit the site of Lambayeque Viejo during the excursion). Excavation of ca. 1578 AD levels at contemporaneous Indigenous and reducción townsites would provide a valuable and unique opportunity to compare the effects of colonization on the experience, response, and recovery of North Coast communities from a powerful El Niño, especially in conjunction with the historic record available in the AD 1580 testimonies. This in turn would help identify long-term historical trends affecting the resilience of North Coast communities to the El Niño phenomenon more broadly, and how those trends might bear on future climate adaptation and resilience-building efforts.

Future visits will be necessary to continue to develop connections with Lambayeque communities and integrate their input into the research we hope to conduct here. Alongside these efforts, our next steps will be to conduct further reconnaissance to identify locations for archaeological testing, such as at Lambayeque Viejo, followed by test excavations at sites to determine their potential to address our research questions. The data gathered during our Sturgis-funded expedition will be essential for acquiring new funding for subsequent field seasons.

Acknowledgements:

We thank the Bob and Judy Sturgis Exploration Fund for their financial support, without which this expedition would not have been possible. We also thank Carlos Elera and archaeologists and personnel at the Museo Nacional de Sicán for sharing their time and expertise, and the generous use of their vehicle for our joint visit to the Pampa de Chaparrí.