Tisher hopes climate timeline provides perspective, serves as springboard for action – Mayewski & Birkel

When Sharon Tisher reflects on the climate crises that students in her courses are inheriting, she sometimes experiences a momentary loss of words.

“My generation are the ones who allowed climate change to happen and benefited in many ways from the conveniences of burning fossil fuels,” she says.

Then, the lecturer in the University of Maine School of Economics and Honors College makes the case to her students that there is no more important time to be alive.

“If you want to make a difference, now is the time, collectively, as a college, as a community, as a nation, and a world … and you can be a part of that in many different ways,” she says.

Tisher knows about what she speaks. For more than a decade, she’s been creating “A Climate Chronology” — a record of events in climate science, U.S. policy, and international policy that spans from 1824 to early 2021.

“I think I can say with confidence that there’s nothing quite like it out there as a way of learning about the history of climate change,” she says.

ASAP Media Services, a student-operated New Media research and pre-production house at UMaine, designed a website for the project, which is in two forms.

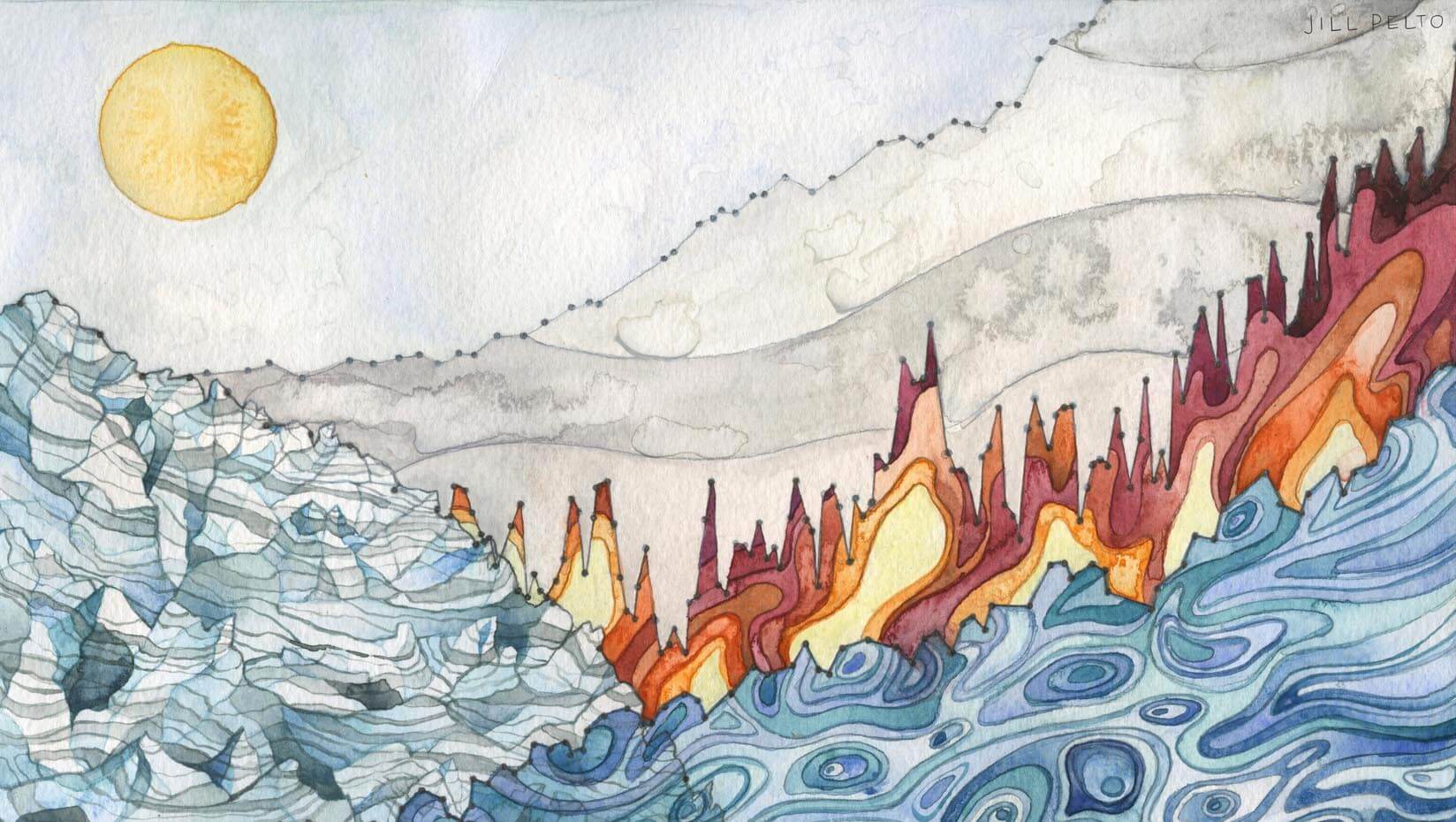

One form of “A Climate Chronology” is a 225-page-and-counting searchable color-coded document with Jill Pelto’s artwork “Landscape of Change” on the cover. Pelto, a UMaine alumna, is a scientist and artist. Her watercolor and color pencil piece “Currents” graced Time magazine’s July 20–27 climate change issue.

“A Climate Chronology” also is a pilot illustrated and interactive timeline of the impacts and threats of industrial and technological developments on Earth’s climate and ecosystems. This presentation is slated for expansion.

Tisher, who graduated from Harvard Law School, is used to successfully making a case. She was the first female partner at Day, Berry & Howard, one of Connecticut’s top law firms. During her 16-year legal career, Tisher usually constructed chronologies as a strategy to lay out and examine important events during a complex legal case.

When she and her family moved to Maine and she transitioned from being a trial lawyer to a UMaine educator, she continued to use the strategy.

“A Climate Chronology’s” initial entry, from 1824, notes that Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier, a French mathematician and physicist, hypothesized the atmosphere played a significant role in mediating temperature on Earth in the article “General Remarks on the Temperature of the Earth and Outer Space.”

The second entry, from 1856, describes American scientist Eunice Foote’s experiment and prediction that carbonic acid, or carbon dioxide, has a warming impact on the atmosphere. All entries are referenced and linked to documents, news or commentary.

The document’s last — for now — two entries are a December 2020–January 2021 piece about the Trump administration’s rush to complete environmental rollbacks before Inauguration Day, and a January 2021 story that notes the 2020 global temperatures tied the record high of 2016, despite a 7% drop in emissions.

In between, there are detailed fascinating entries, including:

In 1951, Rachel Carson, an American marine biologist and writer, published The New York Times bestseller “The Sea Around Us,” which included observations about pronounced warming in the Arctic regions of the Earth.

In 1965, U.S. President Lyndon Johnson stated in a Special Message to Congress: “This generation has altered the composition of the atmosphere on a global scale through … a steady increase in carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels.”

In 1970, Congress enacted the Clean Air Act, with one lone dissenting vote (the Senate vote was unanimous and the House vote was 374–1.)

In the early 1990s, Climate Change Institute director Paul Mayewski discovered evidence in ice core samples of abrupt historical climate change occurring over a period as short as one or two years.

And in 1997, an Exxon Chief Executive Officer claimed the Earth “is cooler today than it was twenty years ago.”

The document and timeline, says Tisher, are intended as “springboards for research, contemplation and action.” By juxtaposing developments, readers can gain “insights into where we have been, where we are now, and where we may be headed in this formidable endeavor.”

In a forward for “A Climate Chronology,” Sean Birkel wrote that CCI and UMaine researchers “have made significant contributions to the scientific understanding of Earth’s climate and human connections — including in the fields of abrupt climate change, climate modeling, ice core proxy records, glaciology, atmospheric chemistry, acid rain, lake ecology, environmental monitoring, and anthropology in addition to effects on marine, forest, and agricultural systems.”

The CCI research assistant professor and the Maine State Climatologist adds that, “‘A Climate Chronology’ joins this effort by providing a comprehensive timeline of climate research, climate policy, law, and some related events in society and technology. ‘A Climate Chronology’ also makes clear that implementation of climate solutions currently lags far behind our understanding of the situation acquired through climate science.”

Tisher utilizes “A Climate Chronology” as a resource in some of her courses. Students in the Honors 112 Civilizations: Past, Present, and Future class can write a paper on imagining Jesus, Dante Alighieri and Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli talking about the climate crisis before a joint session of Congress.

She credits George Criner, associate dean of instruction in the College of Natural Sciences, Forestry, and Agriculture, as being the impetus for “A Climate Chronology.” In 2011, he invited her to develop an energy policy course.

Web designer Jennifer Linton created the pilot timeline so that the climate information would be more accessible to a wider audience. Tisher now is seeking funding for a more comprehensive timeline that takes into account feedback from users about content, format and functionality. She’s working with ASAP Media Service on the redesign.

An informed citizenry is key, says Tisher. “Everything we do in the U.S. counts tremendously in the equation of whether we humans will address the problem of climate change and its most devastating consequences, or whether we will not.”