The Cathedral Glacier: A Disappearing Cirque Glacier in Northern British Columbia

The Cathedral Glacier: A Disappearing Cirque Glacier in Northern British Columbia

Field team members: Ben Partan (1), Scott McGee (2), Bjorn Dulleck (3)

1) Climate Change Institute, University of Maine, Orono, Maine

2) United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska

3) Department of Geoinformation Science, Beuth Hochschule für Technik Berlin, Berlin, Germany

June 26 to August 16, 2015

Funding Support: Dan & Betty Churchill Exploration Grant

Introduction

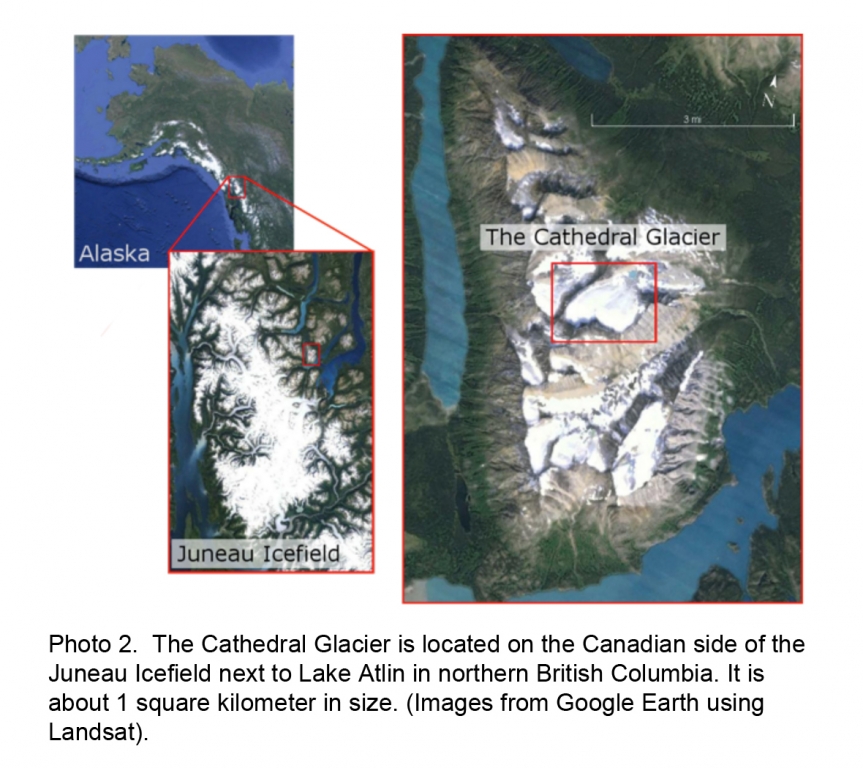

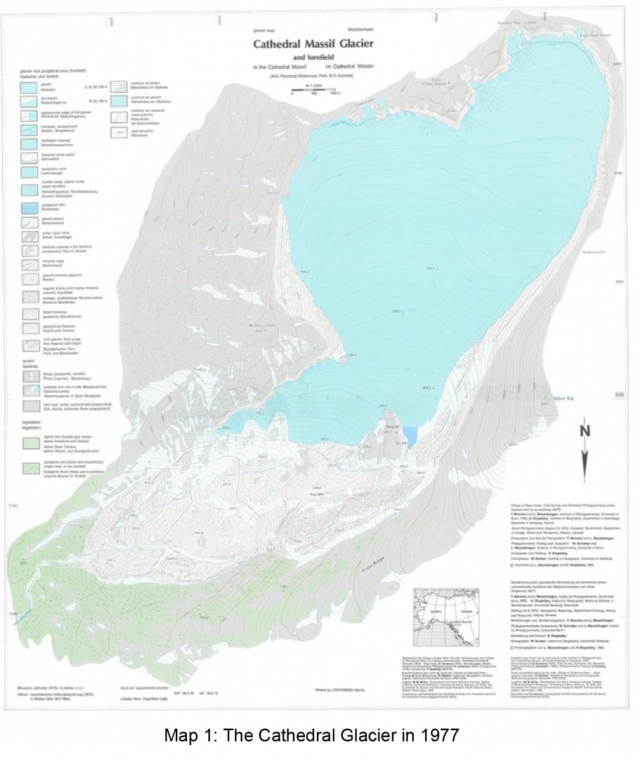

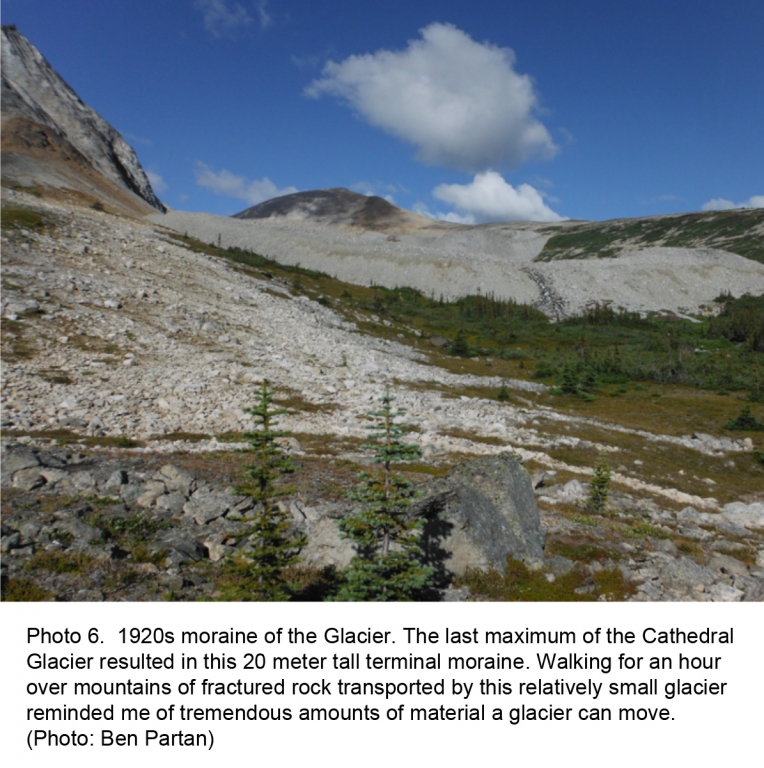

The Cathedral Glacier located near Atlin, BC inside the Atlin Provincial Park is a small cirque glacier (about 1 square kilometer in size) that has been studied by the Juneau Icefield Research Program since the 1970s. The glacier had a recent maximum around 1920 and has been retreating ever since. Since 1977 when the last extensive survey was done of the glacier it has lost approximately half its volume. This recent retreat can be added to the data on other retreating alpine glaciers around the world.

Field Season

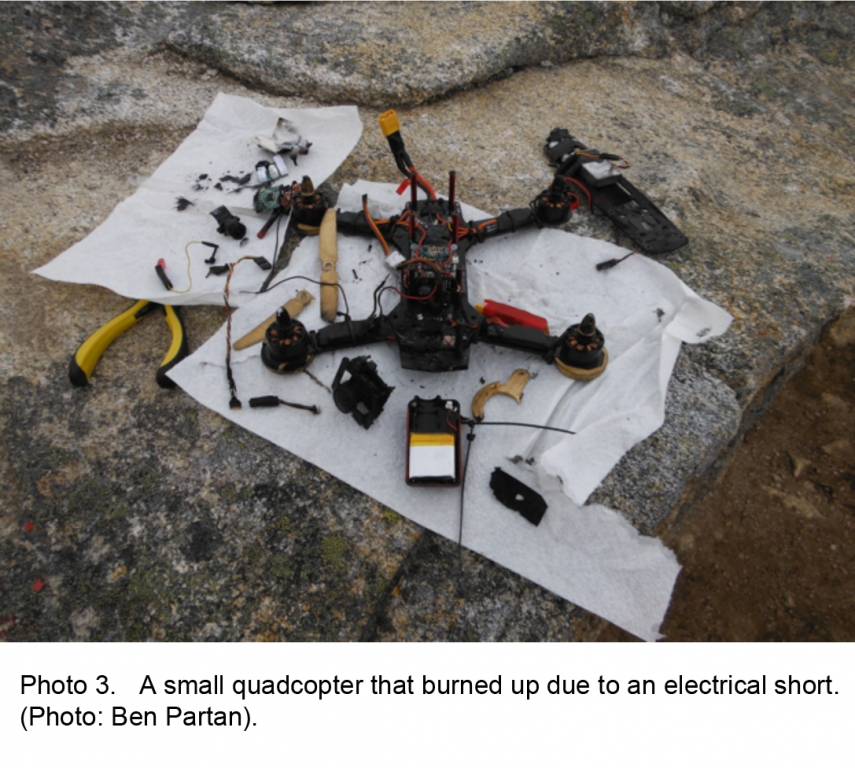

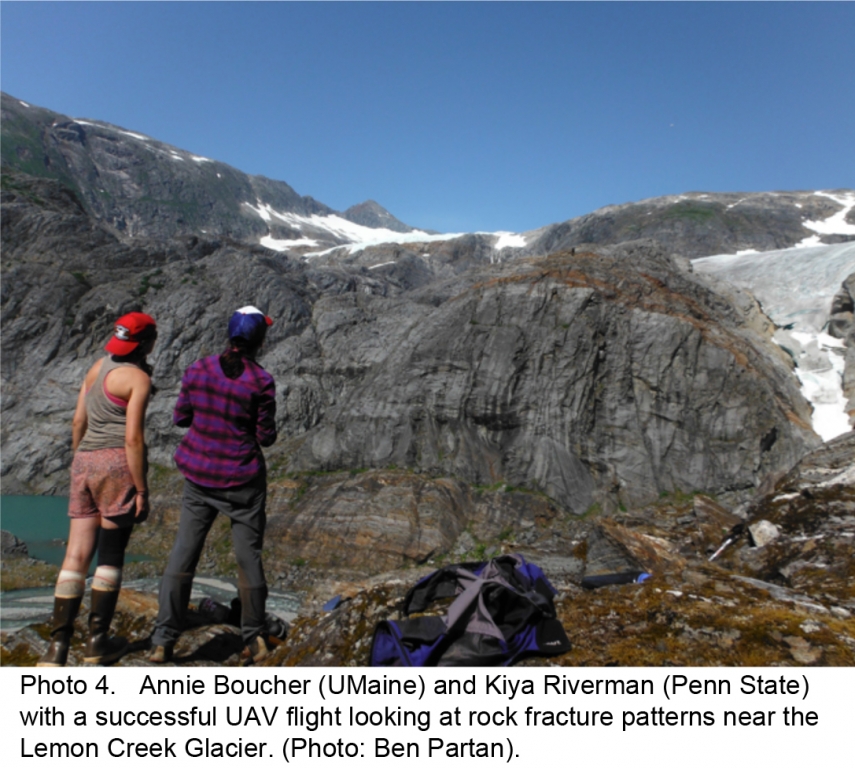

I started out hoping to determine at supraglacial stream depths using small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Bad weather prevented me from flying over my first research area. Then four out of five UAVs crashed hard due to mechanical faults — one crashed AND burned with foot high flames. That was exciting. The days at my second to last research site were too windy to fly to get the data I wanted.

Years working with scientists in Antarctica and Alaska taught me always to have a backup plan in case something goes wrong. It seems four backup UAVs were not enough to make Plan A successful. Activate Plan B.

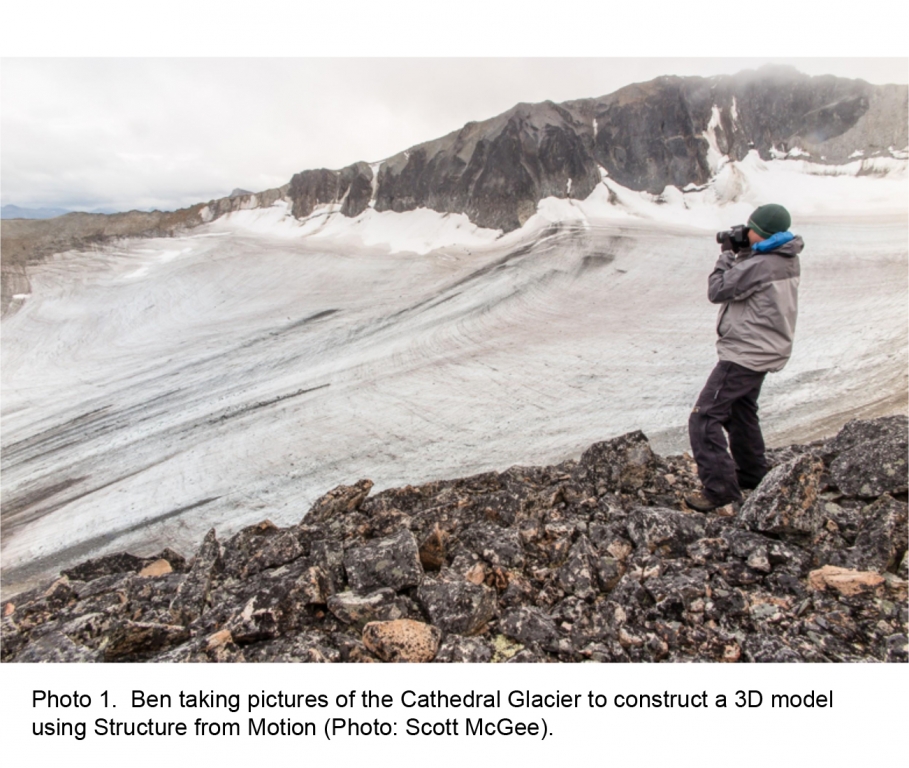

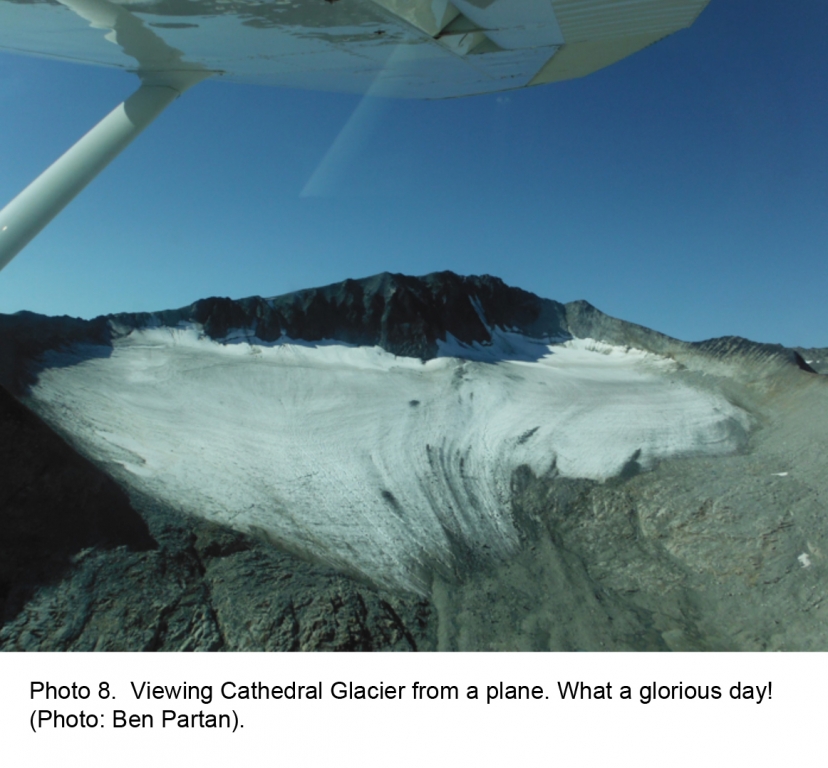

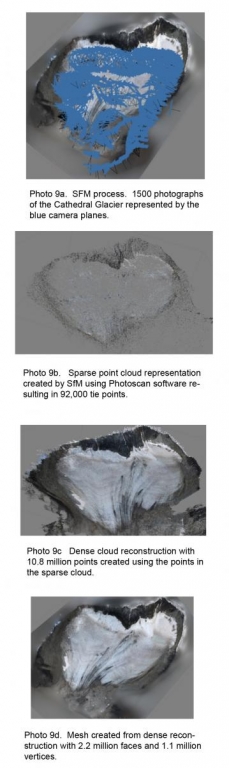

My last research area would allow me to do an interesting comparison between the Cathedral Glacier’s size in 1977 versus where it is today. Even though a UAV would have been very useful to get the photographs needed to construct a 3D model using Structure from Motion (SfM), I could get images from hiking up to the ridges of the cirque surrounding the glacier to complement a GPS survey of the glacier.

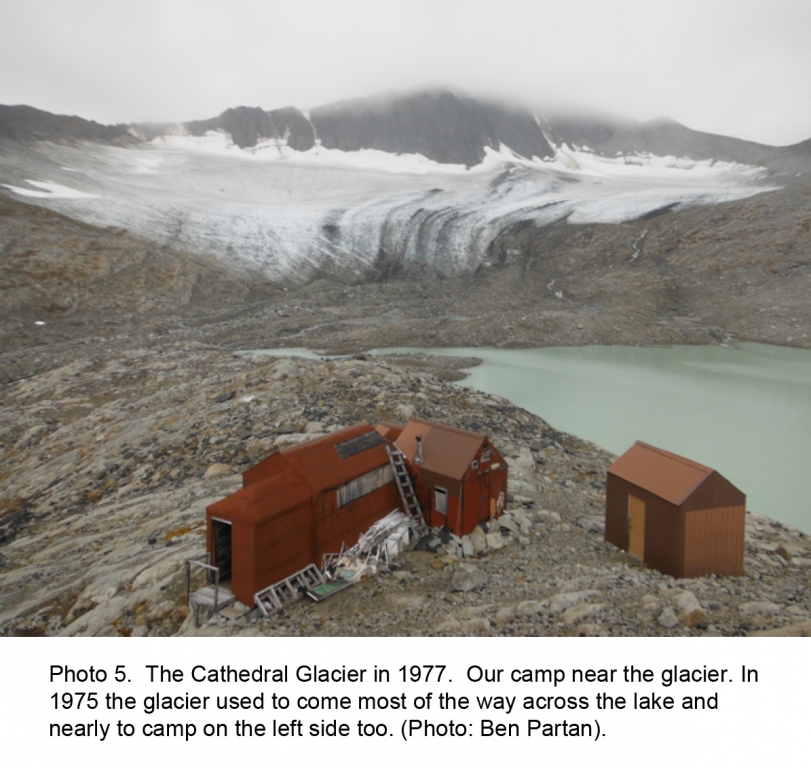

The Cathedral Glacier is located in a cirque on the Cathedral Massif looking over Atlin Lake at the most northern part of British Columbia in Canada. The first high accuracy survey of the glacier was made in 1977. At that time the glacier nearly surrounded the permanent camp constructed by JIRP on a rock outcrop nearby. Now the glacier is about 600 meters from camp and the terminus has retreated about a kilometer.

We spent three days at the camp next to Cathedral Glacier. The first day Scott and Bjorn made a benchmark and started collecting data for the reference base station. I hiked around the glacier and ridges taking pictures for SfM. Despite the JIRP saying of, “It is always sunny in Canada” the next day poured rain harder than Scott or I had seen in Canada in our combined 40 summers on JIRP. The following day didn’t rain but was still cloudy. Scott and Bjorn conducted the GPS survey while I took the remainder of the 1500 odd photos I took of the glacier. Unfortunately it was too windy to fly the DJI Phantom quadcopter I’d borrowed from Penn State graduate student Kiya Riverman.

Following the unwritten rule of field work, the next day when we had to leave the weather was perfect. Sunny, warm and hardly a breeze. We had to hike down to the lake to catch a boat in to town. JIRPers (participants of JIRP) had made a good trail in the ‘70s at the height of research on the Cathedral Glacier but in the intervening years it got overgrown in places. We ended up spending a couple hours bushwhacking through alders and thick pine forest underbrush to get the beach half an hour before the boat got there.

Once in Atlin, a local pilot offered to give us flightseeing tours of the icefield on a rare totally cloud free day all the way across the icefield. We went by the Cathedral Massif and I took a few more images from the air to use in my SfM model.

What is next? 3D Models and Data Analysis

By comparing the GPS digital elevation map (DEM) together with the SfM model and the map made using the data from the 1977 survey it will be possible to determine a volume loss. I am also trying to get past JIRPers who went to the Cathedral Glacier to look in their basements and photo albums for pictures of the glacier. I can use those photos to create intermediate SfM models between 1977 and 2015. Photogrammetric models, like the one done in 1977, require precise knowledge about where a picture was taken and all the angles involved to derive a surface. Today, Structure from Motion can use unordered photos taken from unrecorded locations to create a similar model. That is why I can use pictures taken as snapshots to create the model.

Once I have the intermediate models, by coregistering intermediate models I will be able to create a time series and a rate of loss. The SfM software Photoscan can take the difference between surfaces in order to calculate the losses.

The rate of loss can be compared with the long-term weather data collected by the Canadian government in Atlin. The weather station in Atlin has collected data since 1905. Using an elevation correction, the Atlin weather data can be used to estimate positive melt days at the elevation of the glacier — about 1900 meters above sea level. The rates of volume loss can then be compared to changes in positive melt days over the past four decades.

Sadly, this information can also be used to calculate when the Cathedral Glacier will cease to exist.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the Dan and Betty Churchill Exploration fund for travel expenses to and from Alaska as well as some field expenses. Thank you to the Juneau Icefield Research Program for providing logistical support for my field season. Thank you to Kiya Riverman and Adam Toolenan for adding to the fleet of UAVs for us to crash in exciting ways. Thank you to Paul Illsley for helping get Canadian maps and aerial photos.

References

Beedle, M.J., Menounos, B., Wheate, R.; Glacier change in the Cariboo Mountains, British Columbia, Canada (1952-2005); The Cryosphere, 9, 65-80, 2015

Noh, M.J., Howat, I.M.; Automated Coregistration of Repeat Digital Elevation Models for Surface Elevation Change Measurements Using Geometric Constraints; IIEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing; vol 52, 4, 2247-2260, 2014