Nicaragua’s Climate Change Adaptation Landscape 2017

Nicaragua’s Climate Change Adaptation Landscape 2017

Churchill Exploration Fund Trip Report

July 25- August 11, 2017

Anna McGinn, Climate Change Institute and School for Policy and International Affairs, University of Maine

Adeline Schneider, Undergraduate College of Liberal Arts and Science ’17, University of Maine

Lindsey Stum, Dickinson College ’14, Spanish translator

This research trip served as my first deep dive into the climate change adaptation landscape of the Pacific region of Nicaragua, the case study area for my research. Flanked by a chain of 19 volcanoes, the Pacific region of Nicaragua is fascinating both it is geologic characteristics as well as its equally jarring political history making it a complex and exciting region of the world to explore and study. With the goal of visiting climate change adaptation projects set up to deal with the Pacific region’s chief climatic challenges of flooding and drought, we carried out five site visits in four different municipalities.

We spent our first day in Managua where we experienced the first of many torrential down pours as we walked to the University of Central America campus to meet with a group of environmental engineering professors who specialize in climate change and water research. We showed up to this first meeting looking like we had stepped out of the shower, but luckily it seemed quite normal. I share this because the extremes of intense rains as well as other times of prolonged drought stood out as a central theme of the ways in which people are observing changes in climate. This discussion with the UCA professors kicked off 11 days of interviews and site visits, so we had to quickly jump into the groove of working in Spanish with Lindsey focused on live translating as we worked.

On July 27, we headed north out of Managua to the small town of Nagarote in the department of León. To get from place to place in Nicaragua is an exciting endeavor. The main mode of transportation is the chicken bus also known as an old US school bus that has been retrofit with roof racks and colorful designed across the entire exterior (Figure 2). Let’s suffice it to say that we were chicken bus pros by the end of our fieldwork.

In Nagarote, we met with our first organization, SosteNica. After some initial conversations in their office, we jumped into the pick up truck and headed out into the rural communities that surround Nagarote. We entered right into meetings with rural subsistence farming families, campesinos, where we had the opportunity to learn about the adaptations that they are making in conjunction with SosteNica to deal with prolonged droughts.

After two days with SosteNica, we traveled to León where we met with El Tololamos, a community organization that has formed to support each other in adaptation measures. Next, we met with Nuevas Esperanzas which is a small group focused on working with communities that live on the side of the active Telica Volcano. We then took a much needed trip up into the highlands which provided a slight reprieve from the heat and humidity of León. In the mountains of Estelí, we met up with leaders of the Federación para el Desarrollo Integral entre Campesinoes y Campesinas (FEDICAMP). Our final destination near Totogalpa brought us within 20 miles of the border with Honduras where we met with Grupo Fenix.

With each of these groups, as I described with SosteNica, we ventured out to the rural communities surrounding the main municipal city to see projects that are being implemented with communities that have been either self-determined or deemed by the organization as highly vulnerable to climate change impacts. We walked to farms, schools, health centers, and homes to see the adaptation projects that are embedded in the communities (Figure 3).

Some projects have been introduced by the organization, some have been co-developed, some have been happening for a long time, and others are new innovations from within the community. All the organizations and the campesinos with whom we talked identified drought as the most threatening climate impact, so we focused there on the specific adaptations that are taking place to address longer and changing dry seasons. Here are a few examples of the projects we saw:

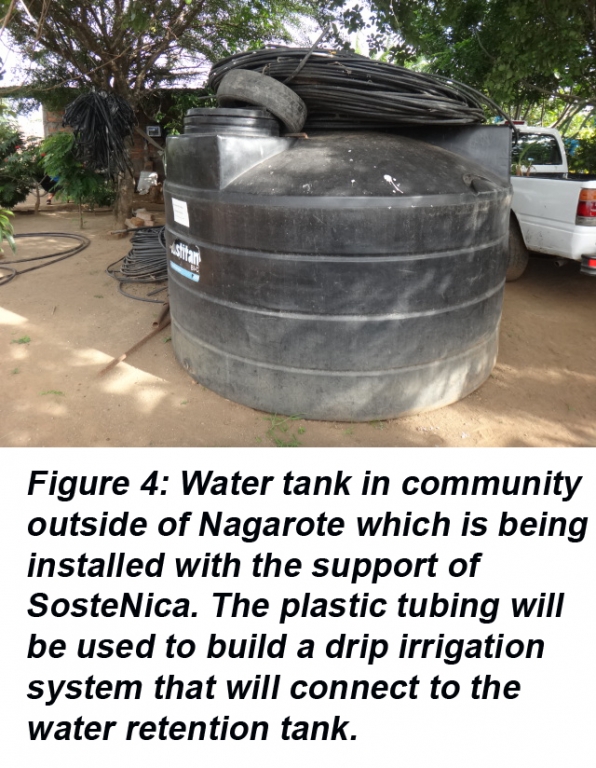

Water retention: Almost all the organization with whom we met have introduced improved water retention techniques in order to capture the water that comes during inundating rain storms to save for the dry season. For some communities, the focus was on retaining water for irrigation, and, in others, the project was for domestic water use. Figure 4 shows a tank that is in the process of being installed at a home outside Nagarote. This was the most common practice we observed being implemented as a result of drought.

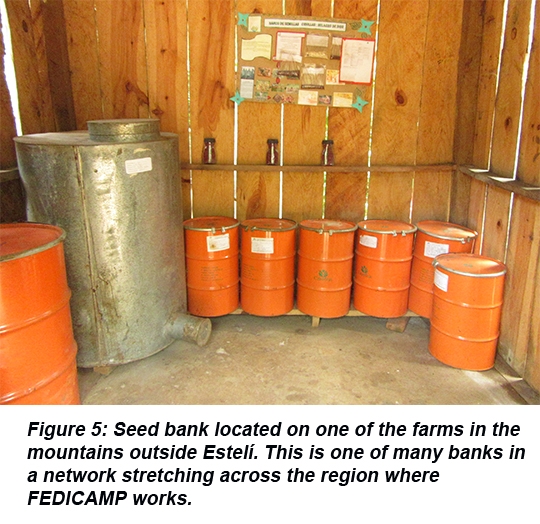

Seed bank: FEDICAMP has worked in their region to develop seed banks to facilitate collaborative seed saving efforts (Figure 5). While seed saving is certainly nothing new, they are now using containers that allow for seeds to be stored for longer periods of time, and, more importantly, the bank brings the community together to share seeds so that if one farmer has a poor crop for a year and is unable to save seeds for the next year, he or she can go to the bank and take out seeds without needing to take out monetary bank loans to finance the next year’s planting.

Deepening wells: Another challenge taken on my many of these groups is that of deepening and widening wells and installing electric pumps (Figure 6). Most recently during the 2015 drought, many of the people we met with reported that their well dried up, so the effort here is to deepen the wells ahead of the next drought.

In addition to visiting these projects and talking to their implementers and primary users, we also had the opportunity to travel to Achuapa to meet with the municipal leaders who implemented Nicaragua’s Adaptation Fund project which was the initial reason that I started this investigation into adaptation in Nicaragua. With our colleagues from FEDICAMP, we traveled to these meetings where we discussed the application process, funding, implementation, and evaluation of this United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change funding mechanism project. Studying this Adaptation Fund project in conjunction with all our other site visits allows for an important comparison between projects of different size and origin. I will be exploring this comparison as I continue with this research.

In addition to our interview and site observation work, we also soaked in the complex and welcoming Nica culture. We enjoyed many meals in the front room of peoples’ homes because that is how most “restaurants” work in the small towns in Nicaragua. We particularly enjoyed the gallo pinto (a rice and bean dish) and fried sweet plantains. The many different site visits allowed us to experience much of the Pacific region of Nicaragua from the side of Lake Managua to the lowlands of León and then up into the highlands of Estelií and Totogalpa. With the patient help of translator and Spanish teacher Lindsey Stum, Dickinson College ’14, I also had the opportunity to put my language skills to the test which is an added bonus of conducting social science research in a Spanish speaking country.

I am looking forward to working with all the interview and observation data collected during this trip. I will also be carrying out my next research trip to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s COP23 in Bonn Germany in November 2017 in order to gather information on perspectives of adaptation projects from the international level. I plan to bring the data collected from both of these trips together to move forward with my research project.

Acknowledgements:

This work would not be possible without the generous support of Dan and Betty Churchill through the Churchill Exploration Fund and the Churchill-Richardson SPIA scholarship. I sincerely appreciate your unwavering support of my graduate school work. Thank you!

Additionally, this research trip was partially supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-1144205. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

The photos in this report were taken by Anna McGinn, Adeline Schneider, and Lindsey Stum.