Chasing the Mammoth Steppe – Exploring the Past and Present of Megafauna in the Arctic

Expedition Dates: July 25th to August 26th, 2019

Expedition Field Team Members: Alessandro Mereghetti 1,2, Dr. Karen James 1, Dr. Albert Protopopov 3, Dr. Valeriy Plotnikov 3

1 University of Maine, Climate Change Institute

2 University of Maine, Ecology and Environmental Sciences Program

3 Academy of Science of the Republic of Sakha

Expedition Funding: NSF CAREER Grant

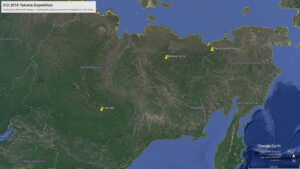

The 2019 CCI expedition to the Sakha Republic (Yakutia) was part of a project to reconstruct the causes and consequences of megafaunal extinctions across Beringia, the once continuous stretch of land extending between the Lena river (Siberia) and the Mackenzie river (North America). The extinction of late Quaternary megafauna took place globally towards the end of Pleistocene. While debate about these extinctions focuses mostly on their causes, not much attention has been paid to how ecosystems responded to the disappearance of large mammals. Arctic megafaunal existence was linked to that of the Mammoth Steppe, a productive grassland ecosystem that was once the largest biome in the world. Its disappearance has traditionally been interpreted as the cause of local megafaunal extinction; however, since large herbivores are known to drastically influence arctic vegetation structure, the disappearance of the Mammoth Steppe has also been interpreted as a possible consequence of megafaunal extinctions. Beringia, the landmass that during the last glacial period connected Eurasia to North America, acting as a land bridge between the two continents, was one of the last strongholds of both the Mammoth Steppe biome and megafaunal populations. Due to its extreme cold, paleontological samples in this region are exceptionally well-preserved and can allow for in-depth reconstructions of past interactions between animals, plants and their environment.

Expedition Goals

To reconstruct the effects of megafaunal extinctions on Arctic ecosystems, our goals for the expedition were:

1) Collect modern plant material to build a reference collection of pollen, macrofossils and DNA to identify paleontological specimens;

2) Visit the collection of the Academy of Science of the Republic of Sakha, a local institution based in Yakutsk that routinely organizes expeditions to recover Pleistocene fossils, to sample relevant specimens dating back to the Pleistocene epoch;

3) Visit the paleontological site of Belaya Gora to search for novel Pleistocene specimens;

4) Visit “Pleistocene Park”, an experimental station close to Cherskiy where scientists are trying to reconstruct the Mammoth Steppe ecosystem by reintroducing large herbivores;

5) Strengthen and develop working partnerships with local institutions for sharing data and findings, to obtain logistical support for future expeditions and develop new collaborations.

Scientific Significance and Data Collection

The Late Quaternary megafaunal extinction events are among the most debated topics in paleoecology. Investigating the diet of past Arctic large herbivores is fundamental to understanding the reasons for their extinction and what effect they might have had on past plant communities. Until now, the direct reconstruction of megaherbivores’ diets has been based on scarce findings of fossil dung and the gut contents of well preserved specimens. Most information about their feeding behaviors comes from isotope analyses of bone remains, which gives insights into the type of vegetation the herbivores were eating but doesn’t allow species-specific resolution.

With the help of Dr. Albert Protopopov we collected reference plant material in the area surrounding Yakutsk, considered by local experts a relict of the Mammoth Steppe mosaic of environments. During our stay in Yakutsk, we also had the chance to visit the archives of the Academy of Science of the Republic of Sakha to examine and subsample significant specimens from their paleontological collection.

The expedition to Belaya Gora allowed us to follow a team of “Tusk Hunters”, local people who explore Arctic riverbeds in search of fossil Mammoth tusks, the only legal source of ivory in the world. Cooperation between the Tusk Hunters and Yakutian academics permits local researchers to obtain access to remote locations brimming with unique fossils, and allowed us to access fossil beds they had discovered. In Belaya Gora we collected samples that will be used to reconstruct the diet and environment of the last glacial period’s megafauna.

The final destination of the expedition was Cherskiy and nearby Pleistocene Park. The Park was established in 1996 to test the effect of large herbivores on permafrost and vegetation, introducing animals living in the area during the Pleistocene (Bison, muskoxen, reindeer, horses). The visit to the Park allowed us to scout for potential sites where we might experimentally assess the effect of large herbivores on modern boreal vegetation. With the help of the founder and director the Park, Sergey and Nikita Zimov respectively, we explored the site and identified locations suitable for herbivore exclosure experiments. These experiments will allow us to understand how a high-density population of large herbivores affects boreal vegetation, and how these interactions (and their cessation) might have affected the landscape of Beringia before and after the Late Quaternary megafaunal extinction event in the region.