2014 Expedition in the Falkland Islands: Fossil, Peat and Sediment Collections

2014 Expedition in the Falkland Islands: Fossil, Peat and Sediment Collections

December 4 – December 22, 2014

Team members: Dulcinea Groff*, Kit Hamley, and Dr. Jacquelyn Gill

*corresponding author

Background:

The main goal of our expedition was to collect sediment records from the Falkland Islands. We collected the peat and sediment records because they contain information about the plants, seabirds, fire history and climate of the Falkland Islands potentially dating back to the last 20,000 years. Seabirds are excellent indicators of what’s going on in the ocean environment. Seabirds and marine mammals transport marine-derived nutrients onto the landscape through their poop. The transport of nutrients is a essential for the vegetation on the Falkland Islands because it is a low-productivity environment. What does this mean? It means that because the landscape lacks native trees and native herbivores (eating and pooping), essential plant nutrients are not being recycled very quickly. Guano from seabirds and marine mammals is an important source of nutrient input sustaining terrestrial vegetation and vital seabird breeding habitats such as tussac grass (Poa flabellata). If you would like to understand in more detail or need a refresher about our objectives, please send us any questions or comments!

The Expedition:

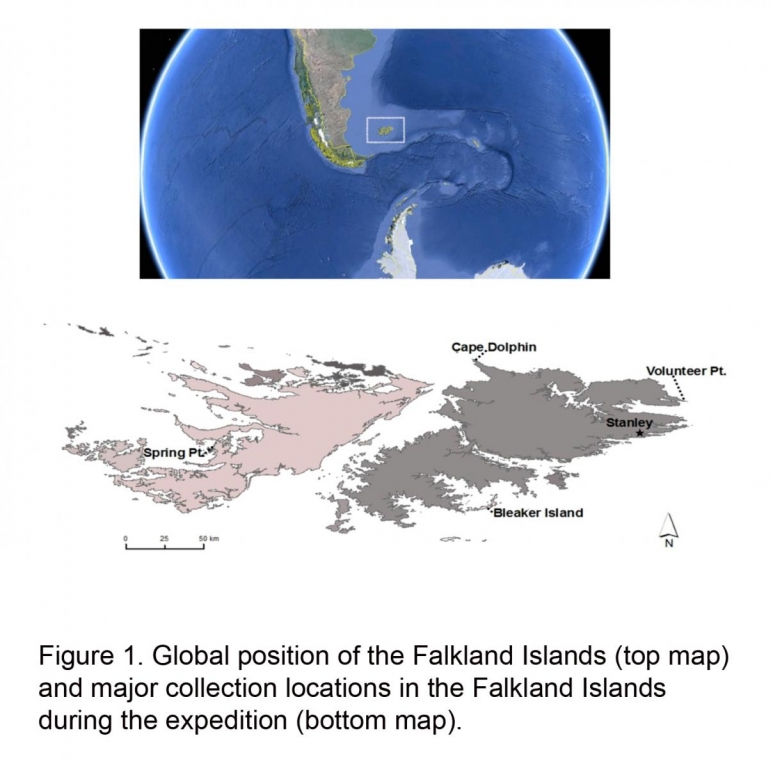

After traveling for two days, we arrived in Stanley, East Falkland on the weekly Saturday flight on December 6, 2014. We met with our collaborators at the South Atlantic Environmental Research Institute and loaded up our research vehicle the next day to ferry over the Falkland Sound to West Falkland. We set out to West Falkland to carry out team member and aspiring archaeologist, Kit Hamley’s research into the extinct Falkland Islands Wolf, also known as the warrah. We travelled across West Falkland to a farm owned by the Evans family where warrah fossil bones had previously been found in a shallow, seasonal pong. While there we walked the pond in search of warrah bones and to our great delight found the back of a warrah skull! Along with the piece of skull we found, through the graciousness of both the Evans family and The Falkland Islands Museum, we were given permission to borrow several warrah bones, which we will send in for radiocarbon dating. The dates we get back will give us a minimum date for the arrival time of the warrah to the Falkland Islands. We also were able to collect a short sediment core from the pond as well as from an eroding peat bank nearby. While this was going on, Dulcinea was constantly collecting pollen from as many flowering plants as possible in order to construct a pollen reference collection that she will create to identify fossil pollen in the sediment records. While traveling across West Falkland, Kit in the driver’s seat (on the right side), Jacquelyn in the passenger seat, Dulcinea would often holler out “STOP!” so she could jump out and make more plant collections. This became a very regular occurrence! Located in what is known as the Fearsome Fifties (51°S latitude), the wind in the Falklands is persistent and strong and must be taken into consideration with every movement one makes. For example, opening a door could result in a squished, smashed or broken leg if the wind were to catch the door (just ask Kit’s knee!).

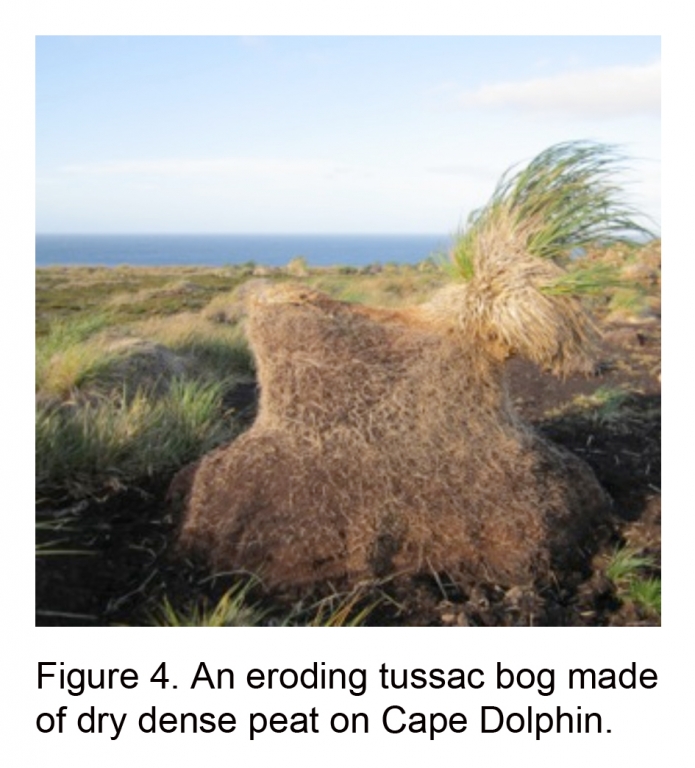

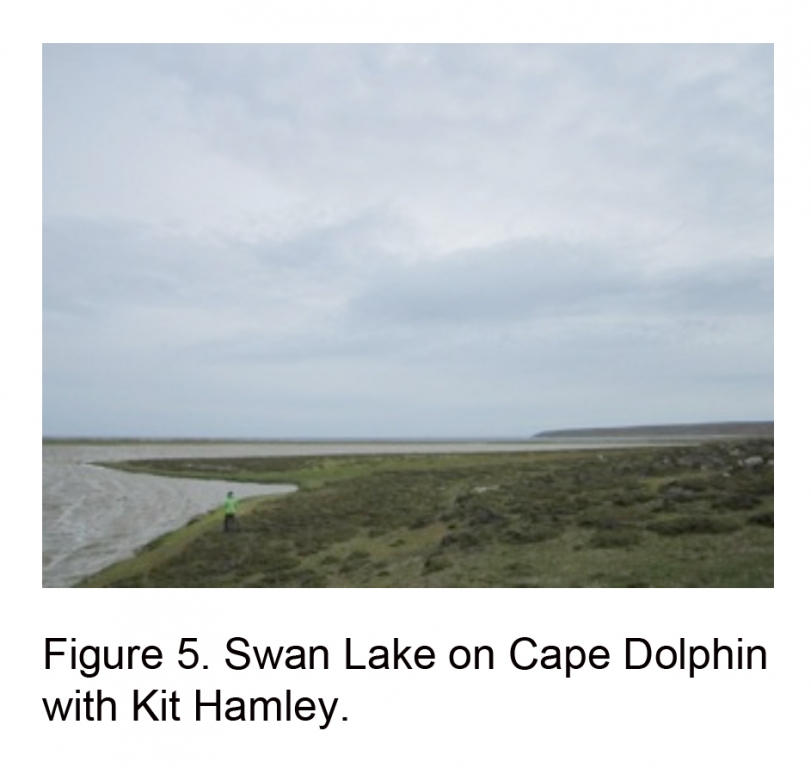

We returned to East Falkland via the ferry and traveled up to the National Nature Reserve at Cape Dolphin, a small peninsula in the north. The Cape is home to many types of birds including the magellanic penguins, which use marram grass, tussac grass, and diddle-dee to construct their burrows. We also found two harems of southern sea lions, several colonies of imperial rock shags lining the coastal cliffs, a colony of gentoo penguins, turkey vultures, and many grazing sheep. We camped at Cape Dolphin for a couple of days to take a look at recovering tussac grass stands with magellanic penguin burrows, and to collect a peat core through a tussac bog. What is a tussac bog? It is a large hump of slowly decaying tussac leaf and root matter with new tussac plants growing out of the top of the bog. The tussac stands at this location were very small and in one location a large amount of erosion occurred in rather old looking bogs. Collecting the 1.5 meter core was challenging because the peat was very dense and dry. We also reconnoitered around the cape and came upon Swan Lake, which may turn out to be an ideal collector and record keeper of the nutrient contribution from the marine environment to the land. Swan Lake is relatively close to the ocean and down slope from abandoned and current penguin rookeries which would capture runoff containing guano over time. We believe this lake has the potential to be an excellent coring site for our next expedition. Dulcinea also collected tussac grass leaf and root material and fresh penguin guano for nutrient and stable isotope analyses, as well as plant material to burn for a charcoal reference collection. The purpose of the reference collection will help in the identification of charcoal pieces in the sediment record, which is a similar idea to the pollen reference collection.

We planned to take a boat out to another National Nature Reserve, called Kidney Island, however our plans were shut down by bad weather in the first week and again during the second week due to boat maintenance problems. We are hopeful to core through pristine tussac grass stands on Kidney Island during our next expedition, when the breeding seabirds are absent.

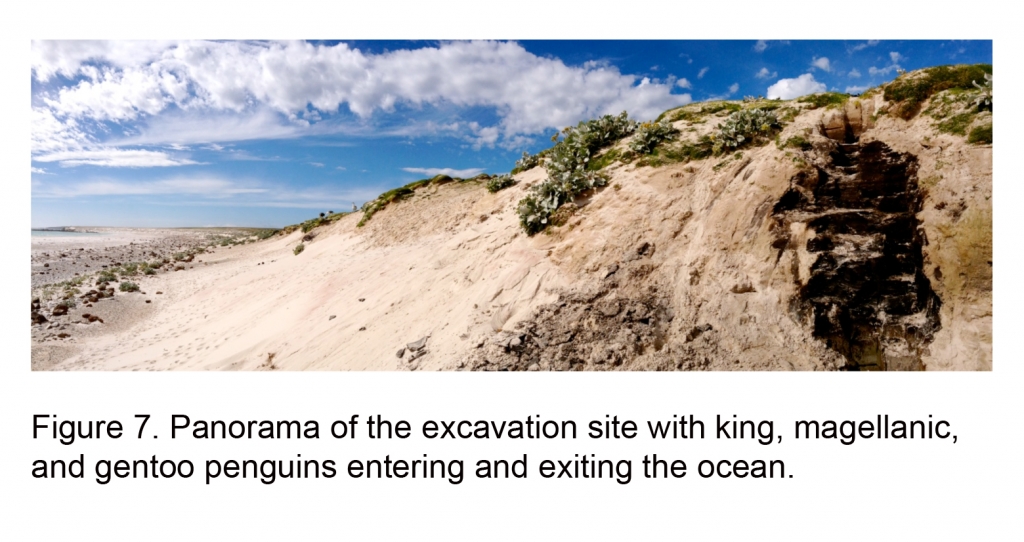

Our next destination on East Falkland was Volunteer Point. We excavated and collected a column of sediment using a shovel, meter stick, and muscle from Volunteer Point, East Falkland. The excavation took place over 6 hours along a beachfront with three different types of penguins, gentoos, magellanics, and kings constantly on the move between the ocean behind us, and their colonies not far away. The penguins were swimming in the waters, laying along the beaches, and making a ruckus with their calls. It was a truly spectacular field site! The dominant vegetation growing on the eroding peat bank between the ocean and seabird burrows is a plant called sea cabbage (Senecio candicans). Although tussac grass is not growing in this location presently, we believe that this peat formed from slowly decaying tussac grass. Throughout the excavated sediment column we found very nicely preserved grass leaf blades! The column is over 2 meters in length and safely made it through to the U.S.

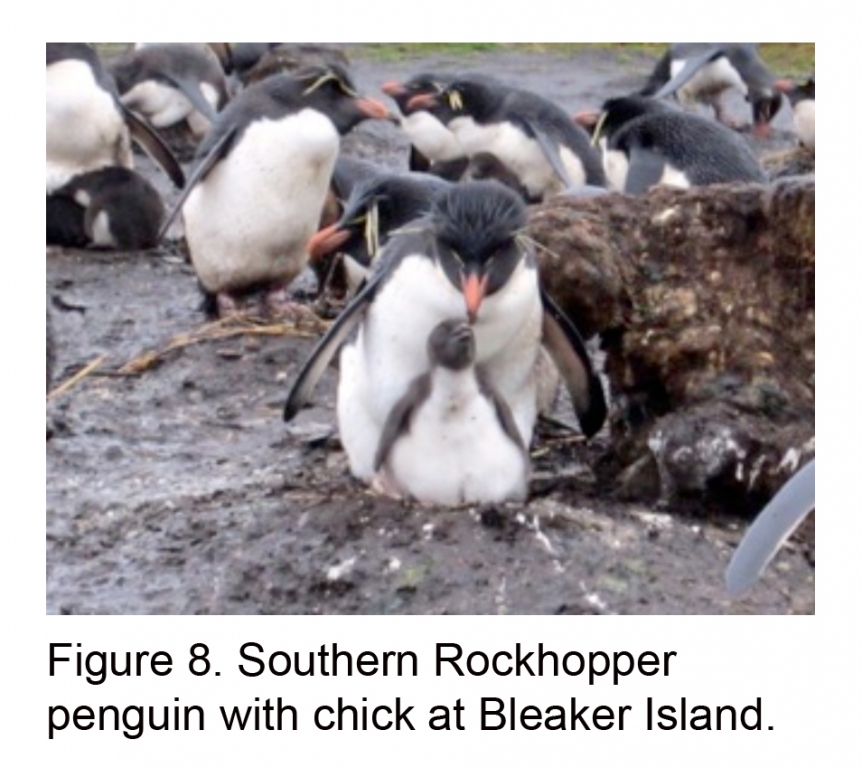

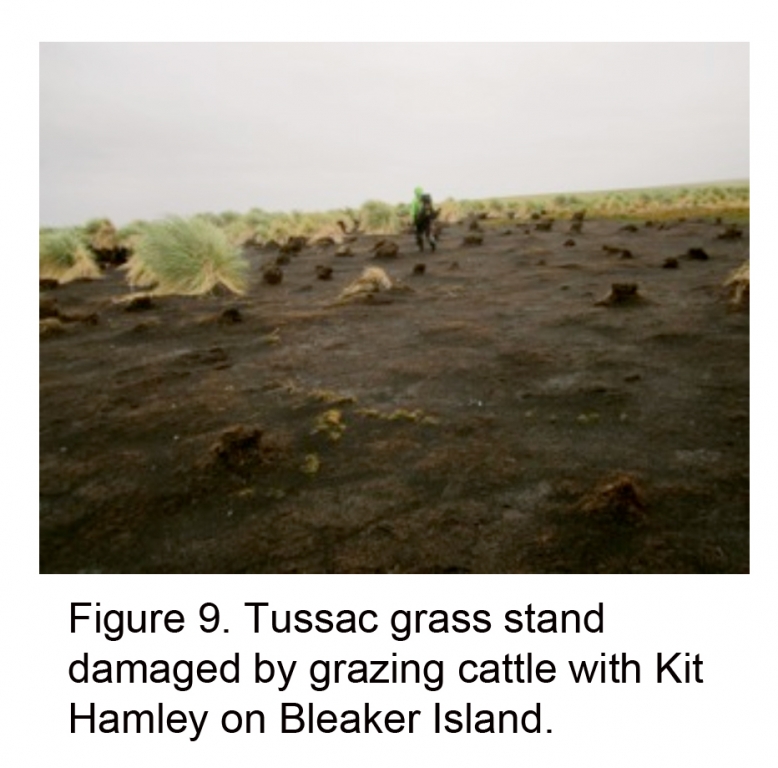

We were fortunate to travel to another island called Bleaker Island, south of East Falkland via the Falkland Islands Government Air Service (FIGAS). The island has tussac grass stands, sea lions, elephant seals, and an abundance of magellanic, southern rockhopper, and gentoo penguins. Dulcinea collected plants for the pollen reference collection, sea lion feces, and more penguin guano. As part of a pilot study, Dulcinea and Kit made surface soil collections (10 cm) along a 20-meter transect within the tussac grass stands to analyze nutrient input from the magellanic penguins burrowing in the tussac. This particular stand is over 100 years old and was planted by Falkland Islander and naturalist, Arthur F. Cobb. While working in the tussac stand we began to feel itchy and later found fleas and ticks from the penguins that had been feasting on us. We were able to collect them, so in the end there was some good from getting fleas and ticks! We collected them because it may be possible to find these insects preserved in the sediment records and we may need them for identification in case they are vectors of human disease. The island is grazed by both sheep and cattle. Cattle graze in parts of the tussac stands only during the winter when other fodder is hard to find and burrowing seabirds are absent. The damage caused by cattle grazing in the tussac stands may be influencing burrowing seabirds like the magellanic penguin.

Now that the cores and column are back at the Climate Change Institute, the next step is to date the column and begin analyzing the preserved charcoal, cholesterols, and heavy metals that are particular to seabirds in the sediment and peat. We are very grateful to all of you who made this research a possibility. Thank you all for your dedication to furthering science and for supporting this project and the start of our careers! We are very grateful to Dan and Betty Churchill for funding this exploratory expedition to the Falkland Islands.