Interior Alaska Summer 2017

What Dung Fungus Can Tell Us About the Peopling of the Americas and Extinction of Pleistocene Megafauna

Field Team Members: Catherine Hamley (University of Maine), Gerad Smith (University of Alaska Fairbanks), Dominic Tullo (University of Nevada, Reno), Kathryn Krasinski (Adelphi University) and Brian Wygal (Adelphi University)

Expedition Dates: June 10 – July 20, 2017

Funding Support: NSF Graduate Research Fellowship and Adelphi University Archaeology Field School

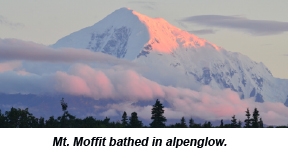

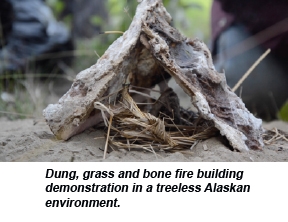

I spent this summer crouched in a hole in the ground that just kept getting deeper. Bent over my trowel, arms and body aching, I spent a lot of time daydreaming about what it would have been like to live in this exact location 14,000 years ago. About what it would have been like to be the first humans in interior Alaska, perhaps North America. About what it would have been like to sit and flake stone tools while looking out across a treeless Alaskan wilderness at herds of megafauna contentedly grazing on grass and shrubs.The site we were working on rests at the edge of an old bluff cut out by a river, which has long since meandered some distance away. The bluff is now covered in large towering trees, which we have strapped tarps to in order to keep rain out of our dig site. As we dig down, the sediment changes from a rooty red organic layer, to silver and yellow glacial loess, a fine-grained sediment that over the course of the summer will work its way into every fiber of my clothing and being.As we dig further into the ground, we are not unlike time travelers. Not only do the sediments change, but the artifacts associated with them do as well, transporting us through changing ecosystems and cultures. Shouts of “Got something!” become more frequent, as we encounter ancient hearths, stone flakes and tools, now-extinct bison bones, and perhaps most excitingly, mammoth ivory. The interactions between humans, landscape and the beasts of Pleistocene-past are apparent in the preserved artifacts.Shortly after humans arrived in North America 14,000 years ago, megafauna populations crashed, leaving the continent devoid of many of its largest and most iconic mammals. In this light, human arrival appears to be synonymous with extinction. However, this extinction event occurred at the close of the Last Glacial Maximum, a time of significant environmental upheaval, making it difficult to disentangle climate and human impacts. Archaeological sites provide us with snapshots of life in the past. They record a time, a place, an activity, and a people. But like their modern counter parts, people move location and change technology, leaving the archaeological record often incomplete or at the very least discontinuous. So, when tackling questions like, ‘what caused the megafauna to go extinct?’ interdisciplinary approaches become our best option for filling those gaps and coming up with the best possible explanation.This summer, when I wasn’t digging in a hole, I was pouring over maps of all of the waterbodies in the area, searching for the perfect location to retrieve a sediment core from. What I needed was a lake deep enough that it wouldn’t have dried out in the past, and one that would contain sediments old enough to span the period I was interested in, ~15,000 years ago up until the present. I pinpointed numerous lakes and ponds which I thought could be perfect, but, this being Alaska, and this being my first field season here, my plans didn’t go accordingly. This is the part of the story in which any remote field scientist will say, ‘Uh huh’, chuckling to themselves and perhaps shaking their head ever so slightly as memories of their first field season flood their thoughts. It is common knowledge among the seasoned, that your first field expedition in a new location, typically doesn’t go completely according to plan.The problem was, Alaska is remote and many of the lakes are impossible to get to in the summer without the use of a helicopter or float plane, not to mention the funding to hire such transportation. Lesson learned: Come back in the spring when you can use a snow machine and core through the ice. I’m learning. I didn’t let this stop me though. Keen on having an adventure and bringing back something to prove to my advisor that I wasn’t just gallivanting around Alaska all summer, I picked a nearby location, put together a team, tracked down some canoes, and rented a 4×4. Away we went.After a few harrowing 4×4 shuttle trips to transport our gear through mud and tight trees, we arrived at the lake, greeted by sunshine and the shock of a mosquito free afternoon. We put our coring rig together, anchored ourselves in the deepest basin of the lake, and retrieved 2.5 meters of core. This is about where our good luck ran out. In the distance, dark clouds had quickly amassed and begun to rumble. On our final coring drive, we hit a layer of frozen sediment that we couldn’t get through (to this day, this still baffles me). Happy to get off the water, we paddled for shore, storm clouds to the rear, packed up and headed out, but not before the rain started. We had two trips to make, so while two people shuttled gear in the 4×4 the other two pulled a canoe out on foot. I won’t relate the entire saga, but will say that after twice getting stuck, losing a few bags of gear off the 4×4, plowing through enormous puddles, and watching a moose and her two calves frolic about in the rain, we made it out with muddy grins, a sediment core and a good story to tell.Much like the archaeological site, the sediments in this core provide us with information about the past. Inside the sediments are pollen grains, charcoal, and Sporormiella, a dung fungus whose life cycle requires it to pass through the digestive tract of herbivores. The difference is that these sediments are continuous through time, so by analyzing them we are able to develop higher resolution records regarding the timing of megafuanal collapse. Developing a precise timeline of megafauna population decline will allow for direct comparison with preexisting paleoecological and archaeological records. By adding the first high resolution Sporormiella records to the current knowledge base regarding human arrival to North America, we can contribute greatly to the decades old debate regarding megafaunal extinction and consequent ecological changes.It was a field season to remember and to build on. I met and learned from many different people with varying backgrounds and experiences and I am thankful that this was just the first of many field seasons in Alaska. Here’s to science and the never-ending quest for knowledge and adventure!