The Westwind II Expedition: South Georgia 2017

The Westwind II Expedition: South Georgia 2017

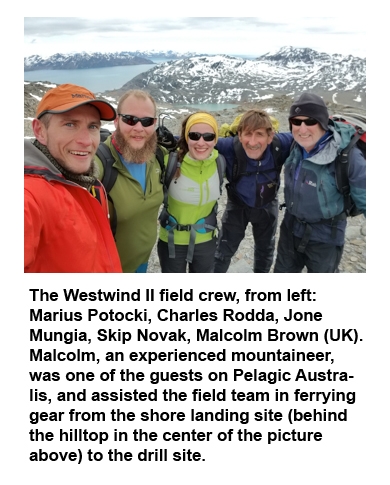

Field Science Team Members: Mariusz Potocki, Charles Rodda, – Climate Change Institute, University of Maine, USA; Jone Mungia – Universidad de Magallanes, Punta Arenas, Chile; Skip Novak – Pelagic Australis, Cape Town, South Africa

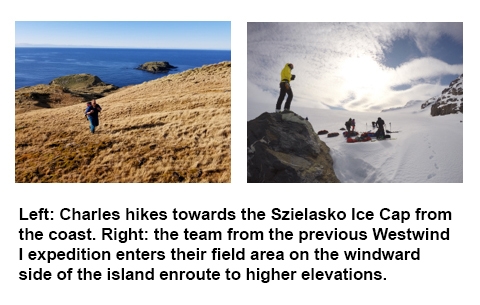

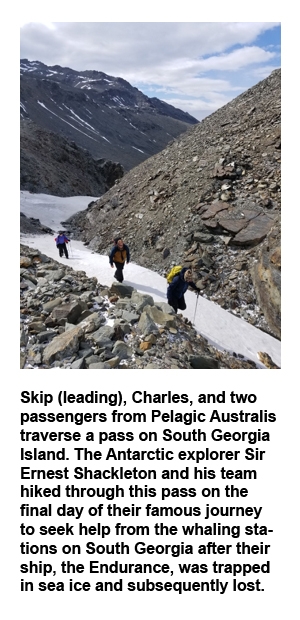

On October 2017, two CCI graduate student researchers, Charles Rodda and Marius (Mario) Potocki, and a collaborating graduate student from the University of Magallanes (Punta Arenas, Chile), Jone Mungia, completed an expedition to the Szielasko Ice Cap on South Georgia Island. The Westwind II expedition was planned by the project’s Principal Investigator, Dr. Paul Mayewski, though he was unable to participate in the fieldwork due to a snapped Achilles tendon he incurred during a training climb. The final member of the field team for the expedition was Skip Novak (South Africa), designer and owner of Pelagic Australis, the 74’ purpose-built high-latitude yacht that served as the expedition home base. The team, along with the crew and passengers of Pelagic Australis, sailed from the Falkland Islands to South Georgia with the intention of collecting an ice core from the Szielasko Ice Cap, a site that our previous reconnaissance and satellite imagery suggested might be a good drilling site for climate investigations.

Located 1,700 km east of the southern tip of South America and 1,400 km from the Antarctic Peninsula, South Georgia emerges from the Southern Ocean at ~54°S, one of few islands in the Sub-Antarctic. The mountains of the Allardyce Range in the central and southern portion of the island rise to nearly 3,000 meters above sea level. These mountains host glaciers that potentially contain records of temperature, precipitation and atmospheric chemistry that are of significance to climate scientists, both for their unique location for monitoring climate of the South Atlantic and Southern Ocean and for their potential for loss in the near future.

South Georgia sits within the Westerlies, the powerful mid-latitude winds that help to drive hemispheric scale atmospheric and ocean circulation, and near the Antarctic Convergence, where cold Antarctic waters meet warmer waters from farther north. Evidence of changes in the circulation of the position of the Antarctic Convergence and position and strength of the Westerlies, over seasonal to millennial time-scales may be preserved in the ice of South Georgia’s glaciers. Because few observational records in the middle and high southern latitudes date back more than a few decades, these records may prove invaluable in helping to shape our understanding of climate in the Southern Hemisphere. Trace level concentrations of chemicals released by human activity may also be present in the glaciers, allowing us to assess human activity and its potential effects on the environment.

Since increasing mean annual temperatures around South Georgia have caused (on-going) rapid shrinking of its glaciers, threatening to destroy the climate records contained within them it is critical that any records in South Georgia be retrieved and analyzed before they are gone forever.

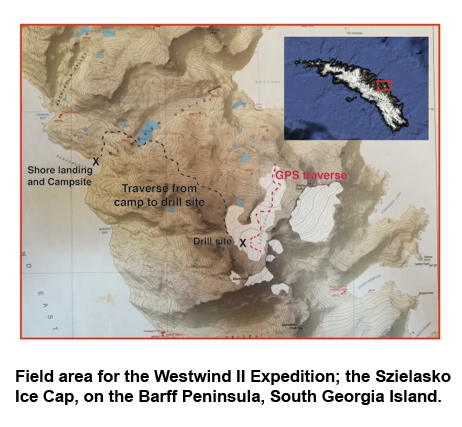

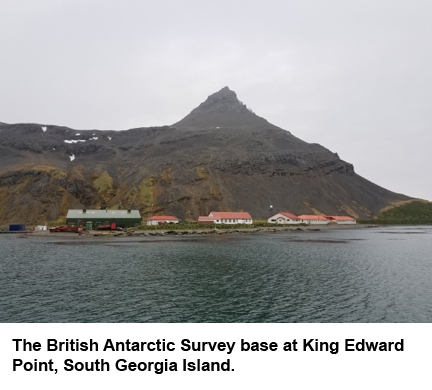

On two previous expeditions to South Georgia (2012 and 2015) Paul Mayewski led CCI members (Mario Potocki, Alex Kuli, Bjorn Grigholm, Dan Dixon, Jeff Auger and Ben Burpee) and cooperating colleagues from Magallenes University (Punta Arenas, Chile (Gino Cassasa)) on an earlier expedition to Szielasko Ice Cap (the focus of the 2017 expedition) and recovered a 15m deep core from the confluence of Esmark and Briggs Glaciers on the windward side of South Georgia – the first ice core ever recovered from South Georgia. Our previous field observations and satellite imagery also suggested that the upper sections of the glacier would be accessible by a traverse across the Barff Peninsula from Cumberland East Bay, near the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) Base at King Edward Point. Satellite imagery showed apparent horizontal layering, remaining ice thickness of circa 30 meters, and minimal ice deformation. The site was selected as the target for the primary ice coring effort for Westwind II. The team hoped to drill a continuous core from the modern glacier surface to bedrock using a gas-powered mechanical drill. That core was to be returned frozen to the Climate Change Institute in Orono for processing and analysis. Results of those analyses would help guide an ongoing deep core-drilling project – possibly establishing the Szielasko as the South Georgia detailed core site if annual layers and intact chemistry could be demonstrated. A secondary goal of the expedition was to repeat a traverse across the eastern lobe of the ice cap made by Gino Casassa (University of Magallanes), on our 2012 expedition, using high-precision global positioning system (GPS) receivers to measure the surface elevation of the glacier. By comparing the current glacier surface to that mapped in 2012, the rate of glacier loss can be calculated.

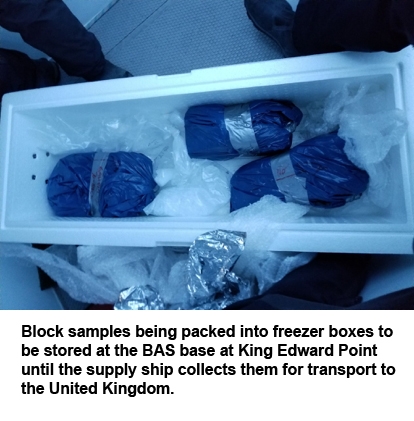

During the expedition, the team experienced exceptionally mild weather that allowed for safe and rapid fieldwork, but encountered drilling difficulties associated with a possible drill malfunction. Rather than drilling a long core, ice blocks had to be collected by chainsaw from several pits excavated on the glacier surface. The snowpit blocks were transported intact to a freezer at the BAS station at King Edward Point from which BAS will send them by ship to Cambridge, UK to be picked up by CCI and sent to Orono. The team successfully completed the repeat GPS traverse during their last day on the glacier.

2017 Westwind II Expedition Journal:

Mario and Charles left the University of Maine on 10 October, travelling to Punta Arenas, Chile, where they rendezvoused with Jone Mungia, and used a necessary 3-day layover to collect the GPS survey equipment needed for glacier surface elevation mapping. The three scientists met up with Skip and several passengers bound for Pelagic Australis at the Punta Arenas Airport for the single weekly commercial flight from South America to the Falkland Islands, another (like South Georgia) British Overseas Protectorate located about one third of the way from the South American mainland to South Georgia. We transferred by van from the airport to the public jetty in Stanley, where we joined Pelagic Australis, spending much of the remainder of the first day stowing our gear below decks and beginning to re-assemble equipment that had been disassembled for transport.

On 16 October, Pelagic Australis left Stanley bound for Grytviken on South Georgia, skippered by Captain Alec Hazell, with first mate Thomas Geipel. Alec’s wife, Giselle, also a member of the crew, had to leave the expedition at the last minute for medical reasons. Less than an hour after leaving Stanley Harbor, Charles discovered that he was significantly more susceptible to seasickness than his experience with coastal cruising in Maine would have indicated.

After a rather fast passage, on the morning of 20 October, Pelagic Australis opened Cumberland East Bay and gained sight of the BAS base at King Edward Point. The yacht tied up at Grytviken, at the head of the bay and the crew and passengers waited for the officer from the Government of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands to arrive to deliver our biosecurity briefing and clear us for immigration.

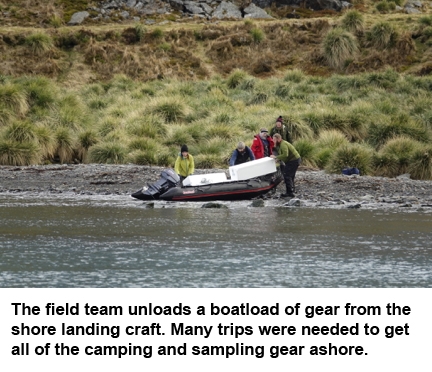

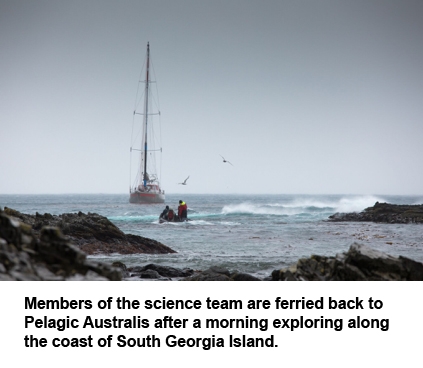

The following morning, Pelagic Australis motored across Cumberland East Bay to bring the field team to their landing site in Sandebugten. With the yacht moored just offshore, inflatable craft ferried the researchers and their gear to the landing site, a short section of beach well clear of the fur and elephant seals that use South Georgia’s beaches for mating and rearing their pups during the Austral spring. Several passengers came ashore to explore, and one, Malcolm Brown, spent the morning and afternoon helping the team carry gear to a cache near the drill site.

Skip and Mario’s experience in South Georgia and earlier visits to the Barff Peninsula proved invaluable as the team was able to find a route to the drill site that could be covered in under 2 hours. Unseasonably mild temperatures and a lack of snow, both on the ground and during the campaign, made for fast walking to the drill site.

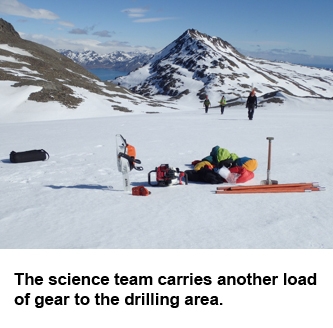

After caching our drill gear the science team spent the rest of the afternoon searching the proposed drilling area for the ideal orientation of features and a place to make a safe drilling platform. Having located these, they returned to camp.

On 22 October, after a cold but dry evening in camp, surrounded by the guttural serenades of the resident elephant seals, the field team woke for an early hike to the glacier. Under bright skies and warm air, the science team assembled gear and began preparing the drill site, while Skip dug a small snow cave into a stable cornice 200m away to serve as a temporary holding area for ice samples.

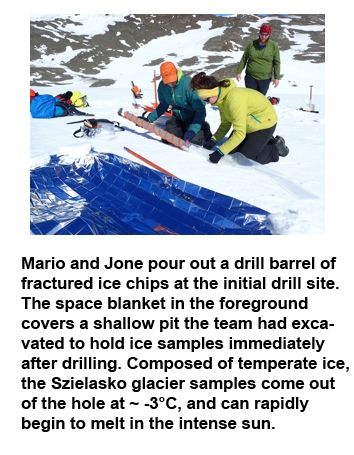

The team drilled to a depth of 6 meters at the initial drill site. Unfortunately, every drill barrel that came out of the hole contained only small chips of ice. Though some breaks in the ice were expected, as in any drilling program, this level of pervasive fracture is unprecedented in the experience of those involved in the campaign. To the maximum depth that the team was able to drill, every sample retreived was broken into lenses of ca. 2cm thickness or less. None of that ice would be useful for laboratory analyses.

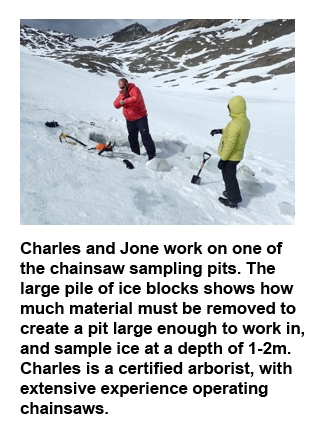

Five additional drill sites were tried, in the general region of the initial drill site, but no intact samples could be retrieved. While the drill was disassembled by the rest of the team, Charles used a chainsaw, equipped with carbide cutting teeth, to excavate a small pit to see if larger samples might be retrieved intact by cutting rather than drilling. Shallow (close to surface) blocks from an initial test pit proved stable, and a plan was made to return the following day to sample blocks from a series of chainsawn pits.

On 23 October, the team began by identifying three areas to try to excavate pits from which to saw block samples. These pits were located at the top, middle, and bottom of a steep slope adjacent to the initial drill platform. The three sites selected were in layers that would have been reached immediately below the surface, at ~ 10m depth, and ~ 20m depth, had the vertical drilling proved successful. In each pit, the upper 0.5 – 1m of snow and ice was removed and discarded, so that annual melt and percolation would not compromise the samples. Samples were then sawn out of the underlying solid ice. In all three pits, intact blocks 30-50cm thick, with tapering square cross sections of 15-30 cm width were retrieved. Several were trimmed slightly, all had orientation marks scratched into their surfaces, and were wrapped in plastic to cushion them for travel, prevent contamination, and minimize melting.

The samples were loaded into a back pack, and Charles hauled them to the shore landing site, while Mario and Jone traversed the eastern lobe of the glacier for the GPS survey. Skip had earlier left the sampling site to break down and pack the shore campsite. Pelagic Australis waited at anchor near the shore so that upon reaching the camp, samples could be immediately loaded into a dinghy and brought to a freezer on the boat. Once the samples were safely stowed away, the camping gear and sampling equipment were brought aboard and stowed.

Once the whole team was aboard, with the intention of minimizing any possible risk to the ice from electrical failure or weather delays, Pelagic Australis motored across Cumberland East Bay to the BAS station, where the team had obtained permission to store ice samples in the base’s large freezer. Once safe passage was made, and the base crew was standing by to receive the samples, the team removed the sample blocks from the freezer, packed them into a padded cooler, and help load them into the freezer. Just before the Austral winter, in March or April 2018, a supply ship will bring food and supplies necessary to keep the base functioning through the winter on South Georgia. That ship is equipped with a freezer and will transport the samples to a British Antarctic Survey facility in the UK, where the team will retrieve them for processing at the Climate Change Institute.

Once brought to CCI, the Szielasko ice blocks will be sampled for trace element concentrations, soluble ions, and stable isotopes (δD and δ18O). The aim of the campaign is to verify that the Szielasko has intact annual scale chemical signals, and ultimately to generate a long-term glaciochemical record for South Georgia. Previous 14C dating on South Georgia ice sampled by CCI in 2012 revealed ice at least as old as 9000 years ago. South Georgia ice cores are expected to reveal changes in atmospheric composition and circulation patterns (e.g. variability in strength and seasonality of the Westerlies, position of the Antarctic Convergence, contribution of various dust sources, and El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) activity). More recent portions of the record will give evidence of changes in human activity around the Southern Ocean, and the consequences of that activity.

After the ice sampling campaign was concluded, the field team had the opportunity to travel around South Georgia for several days with the rest of the passengers on Pelagic Australis. The team took the opportunity to hike up to several glaciers to reconnoiter them for possible drilling during future expeditions. They also had a chance to spend some time with the island’s resident King Penguins. They all look forward to future research in South Georgia.

We greatly appreciate the amazing and highly proficient and professional crew of Pelagic Australis (Captain Alec Hazell and First Mate Thomas Geipel (who also crewed on our 2015 expedition)). Skip Nowak (owner of Pelagic Australis) has been a constant inspiration for our expedition and a close friend. We also thank the Government of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (SGSSI) for granting the Westwind II expedition permission to conduct research on Szielasko ice cap and for their advice throughout the planning stages of the expedition and we thank the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and SGSSI government staff at King Edward Point for their hospitality and for housing the ice core recovered by our expedition and transporting it to BAS (Cambridge, UK).