Archaeological Exploration of the Cotahuasi Highlands, Southern Peru

Archaeological Exploration of the Cotahuasi Highlands, Southern Peru

Kurt Rademaker (CCI), David Reid (Anthropology Dept.)

This month’s field expedition is the latest installment in an ongoing interdisciplinary research program involving a team of senior scientists, graduate and undergraduate students from the University of Maine and collaborating academic institutions in the United States and Peru. The goals of this research are to better understand the early prehistoric settlement of southern Peru, the dramatic climatic and Andean ecosystemic changes at the end of the last ice age, and the connections between early South Americans and their environment. This study integrates a number of scientific approaches, including archaeology, glacial geology, volcanic petrology and geochemistry, and paleoecology.

Prior to this field season, teams of UMaine graduate and undergraduate students have conducted five field expeditions to the remote Cotahuasi Canyon and surrounding highland plateaus in Peru’s southern Andes. It is an absolutely breathtaking place, for the Cotahuasi is the world’s largest canyon – about twice as deep as the Grand Canyon. A number of prehistoric cultures occupied the canyon and its eastern plateau over the last 13,000 years, and each has left their particular mark on this dramatic landscape. Myriad agricultural terraces possibly dating from the Wari culture transformed the canyon into productive gardens, and subsequent occupation by the Inka constructed extensive networks of walls, roads, and administrative centers to take advantage of the canyon’s rich agricultural and mineral resources. Today many small traditional Andean villages occupy the canyon, and Quechua (the language of the Inka Empire) is the primary language spoken. The Cotahuasi Canyon is a very special place where ancient ways of life persist, and rare visitors to this canyon are afforded a glimpse into the past.

High above the Cotahuasi Canyon, the eastern plateau is dotted with extensive bogs, vast herds of llamas and alpacas, and majestic volcanoes covered by large ice caps as high as 6,430 m (about 21,000 feet) elevation. UMaine expeditions to this area since 2004 have conducted glacial geologic study of these ice caps (see our expedition pages from 2005-Firura, 2006-Coropuna, 2007-Coropuna and Solimana) to better understand the long-term history of Andean glaciation and the role of tropical regions in the global climate system, a critical, unresolved issue in climate science. A better understanding of past Andean climate can inform our assessment of the present and predicted future conditions of these glaciers, as well as the likely effects these changes will have on local traditional highland communities. Over the last several years, our expeditions have also found many archaeological sites of ancient hunter-gatherers in this area – these sites may represent the earliest human settlements of high mountains in all of South America, and possibly the world.

This month-long season’s research has two main objectives:

1) Conduct additional geologic mapping and sampling of several deposits of Alca obsidian exposed within the Cotahuasi Canyon and east canyon rim. The collection of additional obsidian samples will help us to define the boundaries of deposits of Alca obsidian, Peru’s largest obsidian source and a valuable resource for lithic toolmakers throughout 13,000 years of Andean prehistory. Geochemical analysis of these additional samples will help us to better understand the large chemical variability we have so far documented within the source area, which spans more than 1,000 km2. Once this work is completed, we will be able to compare the geochemical fingerprint of the source region with the geochemical signature of Alca obsidian artifacts at archaeological sites from all time periods throughout Peru. We will be able to track the movement of Alca obsidian in the past, whether via early hunter-gatherer mobility strategies or vast trading networks in later periods.

Alca obsidian artifacts were recovered at the Paleoindian coastal site Quebrada Jaguay (Sandweiss et al. 1998) suggesting that some of South America’s earliest settlers traveled to the Cotahuasi highlands or traded with other early populations there. Mapping the total extent of Alca obsidian deposits will help us to search for early highland archaeological sites in their vicinity. This season we will visit and sample five deposits of obsidian overall – two within the canyon and three atop the east canyon rim in the Bofedal Pucuncho.

2) Archaeological survey in the Bofedal Pucuncho. This gigantic bog is located within an amphitheater-shaped basin surrounded by three prominent ice caps – Firura, Solimana, and Coropuna – as well as many smaller glaciated volcanic ranges. Today 10,000 domestic llamas and alpacas range here, in addition to their camelid ancestors, the wild vicuña. Because this area is well-watered and productive relative to the surrounding arid puna (plateau), and because Paleoindians probably traveled to this bog on the way to procuring Alca obsidian, we are looking in and around the bog for Paleoindian-age archaeological sites. We are focusing our efforts on bedrock exposures around the perimeter of the bog, especially adjacent to perennial streams that feed or drain the bog, as these are likely locations for rock shelters that tend to favor preservation of ancient organic remains.

Journal

The Inka Roads of Cahuana – January 11-16

David writes:

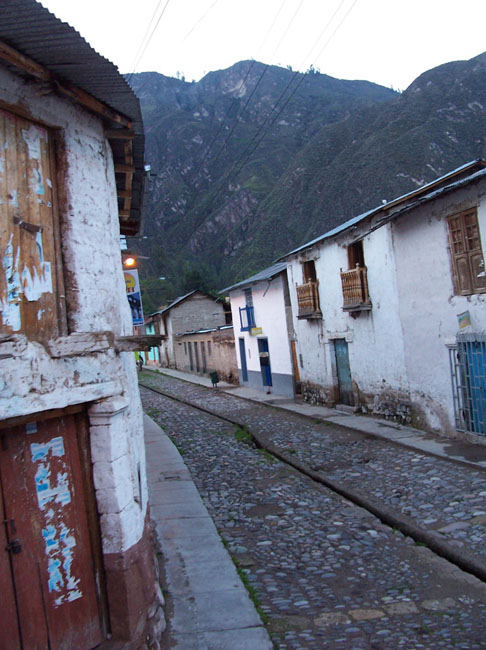

For the first part of the project, Kurt and I would be basing out of the deepest canyon in the world, the Cotahuasi. The first leg of our trip we traveled by bus from Lima to the second largest city in Peru, Arequipa. There we bought supplies and three weeks’ worth of food. With all our gear we had a long and arduous (14+ hours) bus ride to the Cotahuasi Canyon, going up the Majes Valley through the small town of Chuquibamba and finally onto dirt roads to the town of Alca. From the bottom of the Cotahuasi Canyon where the town of Alca is situated, you might not notice the depth of the canyon you are located in. You don’t become aware until you gaze up at the surrounding agricultural terraces, which keep climbing higher and higher, and the switchback roads, which keep zigzagging until indiscernible by the eye.

We were working in the Cotahuasi Canyon to collect numerous samples of the local geological deposits of obsidian in order to obtain a more detailed signature of individual sources. At the same time we were exploring new territory looking for more obsidian deposits. One of our first field days was spent revisiting a previously recorded source near the town of Cahuana (Burger et al. 1998). We located the small obsidian outcrop as we climbed the ancient dirt paths and remaining sections of Inka Road through the traditional farming town. The surrounding peaks are lined with Inka structures, looking down upon the Cotahuasi, once part of the empire.

Returning to the bottom of the canyon, we crossed the raging Cotahuasi River which is ever cutting the canyon floor deeper and deeper. We braved a rickety plank bridge to natural thermal baths, just perfect after a long day in the field.

Cerro Aycano – January 17-19

Our last few days spent in the Cotahuasi Valley, we backpacked out to a large obsidian deposit on the flanks of Cerro Aycano. To get there we walked switchback roads through the town of Ayahuasi, through pastures and terraces, and up ancient footpaths, trying not to disturb the constant herds of goats and sheep that filed by. For two nights we camped in a corral of an abandoned camelid herder’s hut at an elevation of around 3,900 masl. Near the top of Cerro Aycano, we revisited an obsidian deposit and site that Kurt initially sampled in 2004. Located at this obsidian deposit are painted stone tablets found wedged underneath nearby boulders as well as directly upon the obsidian deposits. The stone tablets are flat tabular rocks with one side painted various colors or containing hatchmarks or circular designs. One possible explanation of their presence at the obsidian source is that they were given as offerings or pagos(payments) to the apus (mountain deities) by prehistoric peoples in return for taking the obsidian to make tools. This whole region of highland Arequipa is known for its widespread painted stone tradition, yet the meaning behind the art is still unclear.

During our work near Cerro Aycano, we also noticed an unfortunate trend in weather patterns. It seemed it had precipitated everyday so far. Down in the bottom of the Cotahuasi Valley it had been just rain, yet in the higher altitudes near Cerro Aycano things were more unpredictable. In the early afternoon of our main workday at Aycano, a thick fog set in obscuring the landscape around us. To make matters worse a hailstorm began that gradually turned into sleet to snow and then rain that lasted through the night. Kurt and I had prepared ourselves for the highland wet season with the appropriate gear, which is essential since temperatures fall below freezing most nights. The backpacking trip to Cerro Aycano prepared us for the weather conditions that we’d experience almost every day in the Bofedal Pucuncho.

Bofedal Pucuncho – January 20-28

Kurt writes:

After descending from our camp beneath the Aycano and Condorsayana obsidian deposits, David and I are looking forward to taking the local bus up to the canyon rim and continuing our work in the Bofedal Pucuncho. We planned to do this the afternoon of January 19, but on the way to Alca a local farmer informed us that the bus companies switched their schedules TODAY, with no prior notice. Such unpredictability is commonplace in Peru, and outsiders like us who work here year after year tend to cultivate a healthy sense of patience over time. It is simply out of place to be in a hurry here, despite our scientific deadlines, so we make the best of it and use the extra night in Alca to organize and dry out our gear. It has rained almost continuously since we arrived in the highlands, and we are hoping that the weather above the canyon will be a little drier.

Early morning January 20 the bus departs Alca and heads south along the river before ascending the south rim of the Cotahausi Canyon, comprising a journey of several hours. A landslide has blocked the single-track dirt road, and we are stuck until heavy machinery arrives to clear it the roadway. And when a landslide leaves you sitting in the road for three hours, you might as well make the best of it and play rock Jenga! It’s a good chance to soak up the sun (finally it’s not raining!) and converse with the local people. The single-track dirt “highway” that connects the remote Cotahuasi Canyon with the outside world is traveled almost exclusively by freight trucks and two bus companies – no one can afford their own car. Landslides and muddy roads often stop transport during this rainy time of year, sometimes buses are stopped overnight awaiting assistance, but the buses are always packed full, and people take the inconvenience in stride. Before the 1950s when the road was constructed it took weeks to reach Arequipa by mule or llama caravan. Change has come slowly to this part of Peru, and therefore many traditional highland ways of life have persisted, even as the rest of Peru is rapidly modernizing.

Finally the road is cleared and we travel a few hours south, getting off the bus at the Arma River crossing, a couple hours’ walk west of the Bofedal Pucuncho. After setting up camp in a small side canyon, the first order of business is to contact my friend Ermitanio Zuniga, an alpaca herder who lives in Mauca Llacta in the heart of the Bofedal Pucuncho. Ermitanio will help us transport our provisions on a mule to the east side of the bog, and from there we will explore the perimeter of the bog, searching out potentially early archaeological sites and mapping and sampling two obsidian deposits. Our travel day across the bog is especially memorable as it is brilliant and sunny, and there are thousands of alpacas grazing. We see a baby alpaca or críabeing born, an alarmingly brief process! We reach our base camp site on the eastern side of the bog just as a heavy sleet begins, setting up camp in a dung-filled alpaca corral on the estaciónof a kind local herder, Jorge Talla Contreras. I doubt many people have set up tent sites by troweling through a foot of alpaca dung in a driving sleet storm, but we have!

We spend the next week exploring the entire east and north side of the Bofedal Pucuncho, as well as all of the tributary streams that drain into the bog. We find a number of promising rock shelter sites, and we plan on returning to these shelters to conduct test excavations next season. We also keep an eye out for obsidian outcrops and gravels within local stream drainages. The Bofedal Pucuncho contains at least two spatially separate and chemically distinct sources of obsidian that probably originated from local inactive volcanoes, and this obsidian is distributed in pyroclastic flow deposits over many hundreds of square kilometers. Where rivers or roads cut through these deposits obsidian erodes out in abundance. Mapping the extent of local obsidian deposits is critical to understanding the prehistoric use of this area, as these high quality obsidian outcrops would have been an attractive resource for early hunter-gatherers, especially considering that large herds of camelids have grazed here for thousands of years. With abundant fresh water, natural rock shelters, game animals, and high quality lithic raw materials, the Bofedal Pucuncho may have been an oasis in the otherwise challenging puna environment.

The weather up here is difficult at this time of year – each day we get wonderful sunny mornings, but around 1 PM it begins to rain, by 3 PM we get hail and thunderstorms, then sleet, and finally wet snow in the evenings. It is a challenge to stay warm and dry, and I find myself wondering how prehistoric people might have coped with these conditions, without the benefit of nylon tents, synthetic sleeping bags, and the rest of our modern-day technological trappings. I keep thinking that down on the coast – just 150 km away – it is warm and sunny. Now having camped and worked in the Andes in the wet southern summer (December–March) and dry southern winter (June-August) seasons, a strategy of seasonal mobility between the coast and the highlands to take advantage of seasonally available resources – not to mention good weather – is making a heck of a lot of sense!

Perhaps one of the best findings from our archaeological survey work is the discovery of coastal lithic artifacts at several terrace sites here in the bog at around 4,500 masl. Pink and lemon yellow chalcedony, gray quartzite, and petrified wood projectile points and debitage on the surface of these sites attest to long-distance movement of people between the coast and the highlands or exchanges of artifacts or materials between separate coastal and highland groups. What we do not know yet is the age of these materials – only excavations and the recovery of radiocarbon-datable organic remains will tell us that – but at least now we have found a set of good sites to excavate when we return next season.

We backpack all day to Arma to catch the bus back to Chuquibamba and Arequipa (only a 10 hour trip!), and while we are waiting the hospitable Huisacanio family serves us fried mountain trout, pulled straight from the roaring Arma River and served fresh from their bus stop kitchen at the Arma canyon. Now we can look forward to the creature comforts awaiting us in Arequipa, our upcoming lab analyses back at UMaine, and of course, planning our next season of field work for this coming June-August.