West Antarctic Ice Sheet Stability: Glacial Record from the Ohio Range of the Horlick Mountains in the Bottleneck

West Antarctic Ice Sheet Stability: Glacial Record from the Ohio Range of the Horlick Mountains in the Bottleneck

Hal Borns, Aaron Putnam, UMaine

Robert Ackert, Sujoy Mukhopadhyay, Harvard

December 15, 2004 to February 15, 2005

The goal of this cooperative project is to document the former high stands and assess the stability of the West Antarctic ice sheet at the Ohio Range near the head of the Mercer Ice Stream. The field location is situated in the “Bottleneck”, a unique, reatively narrow passage in the Tansantarctic Mouintains connecting the West and East Antarctic ice sheets. This research will involve geologic mapping of glacial deposits combined with comogenic surface exposure age dating.

December 29, 2004

Aaron writes from McMurdo:

We arrived in McMurdo 21 days ago, and have been very busy organizing the necessary equipment and provisions to sustain us in the field for about four weeks. Our training and preparations have served as a wonderful introduction to just about every tool and skill one could think of using for the field, far beyond my initial expectations that this would be a strictly geological experience. Whether it is banding pallet loads, driving ‘Mattracks,’ repairing snowmobile engines, operating differential Trimble GPS systems, or learning how to rescue fallen crevasse victims, we have had some introductory level of training. We now realize the breadth of knowledge required to function in the deep field and obtain the raw scientific data is absolutely amazing.

When not packing or attending some training session, our time has been spent making use of the 24 hours of sunlight. We seemed to have all found our individual niches here — for me that might entail going for runs out to the sea ice, up to the ‘golf ball,’ or up to Ob Hill to pay respects to Scott and his ill-fated partners. It is truly amazing to peer out at such an expansive landscape, and to have history that seemed fictional become real. To imagine what our predecessors endured for our being able to study this magnificent continent is harrowing and inspiring at the same time.

Other than exploration, we have all enjoyed the various thrills available here. Dr. Ackert and I, for instance, took part in the ‘Polar Plunge’ at the New Zealand Scott Base, where we each earned our patches by diving into 28°F water wearing nothing but safety harnesses. It was bloody cold, perhaps preparing us for everyday life in the Ohio Range. The next day, Dr. Mukhopadhyay and I, the Antarctic rookies of the group, were also fortunate enough to be approached by a couple of curious Adelie penguins on a terrestrial deep field expedition of their own! As a protected species, it is illegal to approach penguins or disturb them in anyway, so to see them close up is indeed fortunate.

All in all, the experience has so far been rounded and full of surprises – and the expedition has only begun. Tomorrow morning we depart for South Pole station, where we will quickly transfer our gear and food into four Twin Otter loads, and hopefully be flown to the Ohio Range that day. From then on, the expedition I am guessing will change gears into an entirely new set of experiences — and I think we are all ready and excited for the change.

January 1, 2005

The Deep South

The veil that has been obscuring continental Antarctica has finally been lifted, as I find myself in the Ohio Range entering a new year. The last days in Antarctica were essentially waiting days, passed by exercises in GPS, and eating McMurdo food.

During one session in processing GPS data, Beth, our resident NAVCO GPS expert, informed Sujoy and me that some Adelie penguins were spotted emerging from the snowstorm preventing us from traveling to the South Pole. We took our first opportunity to scramble along the road skirting the Hut Point embayment, which lies at the top of a rather steep volcanic scree descending towards the sea ice. We spotted two Adelie penguins and one emperor penguin milling about at the edge of the ice, just before the scree. We were somewhat disappointed, as the penguins were far off and hard to see. After a few minutes we turned to head back towards the lab, deciding against going closer for fear of a reprimand from NSF.

As we walked up the road, the penguins, almost as if they sensed it was their last opportunity to get a closer look at these strange red-jacket creatures at the top of the slope, began their determined ascent of the volcanic rubble. Sujoy and I halted, along with a few other penguin-watchers, and stood while the penguins set their path directly towards us! It was amazing, out of all routes, the penguins chose us as their bearing. Their ascent was accompanied by squaks and hopping, with the occasional comical faceplant as a bird would fail to negotiate a large rock in its path. Precariously balanced, wings spread wide, they still moved with about twice the speed up the slope as the average American could. Not bad for flightless sea birds!

The two Adelies neared the snow berm directly at our feet, merely a meter-and-a-half away. They did not master this particular obstacle, perhaps due to the front-end loaders roaring by, though they attempted to wallow up as if swimming… Seeing our first wild penguin was certainly a joy for us both, as I was worried there would be no opportunity on this expedition (especially once we reached our inland destination).

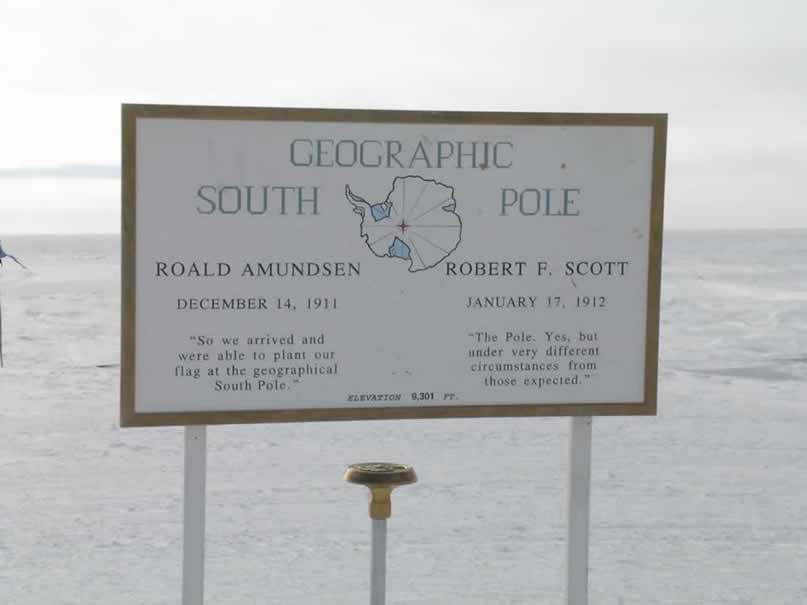

Upon the dissipation of the snowstorm, Robert, Sujoy, Peter and I boarded a C-130, and two hours later found ourselves where all lines of longitutude converge, and every direction points north: the South Pole. It was like landing on the moon, with a vast snow-covered ice sheet expanding as far as the eye could see in every direction. It felt wonderful to exist, if only for a little while, at the same place that Norwegian Captain Roald Amundsen first set foot on December 14, 1911. Of course now it has a very industrial appearance, with the construction of the new South Pole Station. The old station, located underneath a dome that is being buried alive by drifting snow, gives the hint of the Planet Hoth.

A ceremonial pole, and the annually surveyed geographic pole are marked just outside of the station – and are surrounded by the flags representing the member nations of the Antarctic Treaty. Just beyond the ‘pole,’ were the resultant sculptures from the Christmas celebration at South Pole Station. They were highly creative, depicting the Rapa Nui stone heads, sport cars, and various gods with sacrificial pedestals erected in front. I have a feeling that the only things sacrificing their existence were in the form of celebratory libations – but you never know with the Pole People…

We stayed at the Pole for one night, where I had the privilege of sampling a much better cup of coffee than was offered at McMurdo. I also monitored the strange effects of high-altitude on my body. I slept in a strange jamesway hut with no lighting through the main corridor (which made it bloody difficult to find my way around). I essentially had to feel my way to compartment number 5, and then rip open the shade to let the relentless sun illuminate my abode. It was a quaint little room, with the bare necessities – nice, simple, and warm.

In the morning, I spent my time man-hauling sleds full of rock boxes and frozen food to be loaded onto the Twin Otters for our trip into the field – reminiscent of a fraction of what Scott’s men Wilson, Oates, Bowers, and Evans had to endure at this very place 94 years prior. It was here that I really noticed the effect of altitude on my endurance, as I surely felt a bit more winded than usual (this of course, probably had to do with hanging around McMurdo eating copious amounts of food, as well).

Our amount of gear required at least two trips, with a third to arrive as a re-supply. Peter Braddock, our trusty mountaineer, and I left on the first trip to the Ohio Range to set up camp. After about 2.5 hours, we descended through the breathtaking cliffs and canyons of the Ohio Range! Catching a nasty downdraft in the Otter we dropped accidentally at a rate of 700 meter/second, which had my stomach in my throat for sure. But the pilots recovered from the drop, and we coasted safely to a bumpy landing on the sastrugi-ridden snow north of Darling Ridge.

The shear scale of this place is hard to qualify, or even convince yourself of while you are seeing it. The cliffs rise to about 350 meters above the ice sheet, accented by the looming 2867 meter Mt. Glossopteris and Mt. Schopf, providing an impressive backdrop for the camp Peter and I were to set up. We spent that day setting up camp, finishing around 2100h. Robert and Sujoy joined us with the second load at around 1900h, and helped us get that unpacked and set.

Once camp was in relative order, all four of us sat down to a late-night shrimp stir-fry dinner, where we brought in the New Year our first night in the Ohio Range. With a glass of wine we toasted to a productive and exciting field season, as well as to actually getting out into the field in one piece. Robert opened a package from his children, which contained fun noise-makers and bubble solution that we enjoyed over the first glass of Scotch in the year 2005. With that, we were off to bed as the sun skirted the southern sky above the Buckeye Table, illuminating what would be our home for the next month.

January 2, 2005

The Tuning Nunatak, pt. 1

Today was the first day of fieldwork – essentially a shakedown for testing our equipment, and become familiar with sampling. It took us a while to get ready this morning… I arose and got the water piping hot for drinks and oatmeal, and the rest shortly followed as the sounds of my clanging must’ve indicated the availability of warmth and sustenance. The weather was perfect, with temperatures just around freezing, no wind, few clouds, and perfect visibility and surface definition. We set out westward toward the large bluffs of Darling Ridge, and a small speck on the horizon known as the ‘Tuning Nunatak.’

The going is slow over the snow, as the wind-scoured, sastrugi-laden surface produces countless obstacles to navigate in the rather light Tundra II ski-doos. Laying out the flag route, it took us a while to approach the bluffs – enhancing our already eager anticipation of what geological clues they might provide. We finally arrived at the ‘wind-scoop,’ which is a deep mote carved out of the ice by wind and radiant heat from the rocks of the underlying mountain. This one was approximately 15 meters high, and the blue-ice below the large escarpment was concentration glacial erratics into a significant ice-cored lateral moraine. The ice cliffs underfoot, the moraine below, the towering granite cliffs soaring high above, and the impressive network of crevasses propagating through the ice were all such an impressive sight!

We drove a bit further to scout out a route into the moraine for future use, but were diverted by a series of large crevasses. Following the north-south trending crescentic crevasses, we wound our way to Tuning Nunatak, a structure worthy of exploration on such a perfect day. We all got ready, and as I went to reach for my bag of mountaineering gear, with crampons and a harness, and I was shocked to find that it wasn’t on the sled! The true meaning of ‘shakedown’ reared its ugly head, and I had to scold myself for such ineptitude on the first day! This, of course, presented an obstacle for me, since I had to cross a ridged, heavily crevassed region of blue ice to gain access to the Nunatak. I was certainly kicking myself for forgetting the bag, and the thing I had looked forward to the most, walking over glacial ice, was now something I could not easily accomplish – and had to admit to my superiors.

Luckily, I had earlier taken the precaution, and placed an alternate pair of ice-gripping wire that could be stretched around the bunny boots. This gave me a surprising amount of traction, and I ended up getting by just fine even on the steep ice. However, I was very lucky, and definitely learned a lesson for the future – don’t forget anything!!

However, ironically, those who were responsible and remembered their gear actually had worse problems. Here I am referring to Sujoy, whose crampons would not stay on no matter how well you tightened the straps. He ended up having to use a similar pair of cleats for his bunny boots. If I had remembered my gear, I am certain I would’ve had the same problem as he, as we both had crampons meant for the Bunny Boots, which are not suitable for reliable ice-walking. From now on, I will attempt to wear my hiking boots for such endeavors, with a pair of reliable crampons. Hopefully they will not get too cold.

Once on the Nunatak, we found several interesting features. The entire peak is composed of a fine-grained granite, but angular pieces of pegmatitic granite were perched in various places, along with foreign shales comprising most of the thin matrix occupying the nooks and cranies of the rock. The top also was polished, possibly due to old glacial exploitation of a slickensided joint-face.

We sampled two erratics and a mafic enclave in the bedrock. It was a good introduction to sampling procedure, where we first measured the amount of the sky-field that is shielding the sample from cosmic rays (in the case, the primary shielding was caused by Darling Ridge to the south). Then, elevation, lithology, location coordinates, all accompanied by a sketch of the sample in situ were recorded. A sample bag was then labeled, the outcrop photographed, and finally removed the sample using a rock hammer. I worked on the mafic enclave, while the others chose granite erratics. This rock type is significant because it may contain clinopyroxene, which can be used in small amounts to obtain exposure age using the amount of 3He. I’ll try to detail the procedure later.

We then left for home, and ate a late-night fish dinner. It was a successful first run, but we definitely encounter room for improvement (me in particular). Hopefully tomorrow will yield similar weather so we can explore the moraines around Discovery Ridge and Treves Butte!

Discovery Ridge Moraines and Sampling Strategy

Our crew explored the other edge of Darling Ridge today, to the east of camp. I awoke at 0640h and rendered the water hot and the coffee strong for the emerging scientists. After breakfast and organizing gear, we rode the ski-doos about 7 km out to Treves Butte, which with the sastrugi took about an hour. Nearing the bluffs, we entered a blue-ice zone revealing a beautiful garden of erratics. Drawing closer, an ice-cored moraine appeared beyond the increasing concentration of rock emerging from the sublimating ice. After a bumpy ride, we arrived at the system of ice-cored moraines previously described by Mercer in the 1960’s.

The mélange of lithologies comprising the moraines was astounding – quite the opposite of what I expected. Erratics eroded out of the Permian tillite were of a myriad of different Gondwanaland origins, with perfectly preserved striated cobbles. If one was unaware of the existence of the tillite, the moraines would have been utterly confusing… With a mixture of wet-based Permian cobbles and cold-based supraglacial debris, there is no telling what conclusions may have been drawn!

During the day we sampled a transect across the profile of the largeice-cored moraine. The moraine appeared to be a medial moraine formed by the confluence of a nearby alpine glacier flowing north from the Discovery Ridge cliffs, and a small stream from the ice sheet flowing through a gorge in the bedrock. The gorge is curious, since there is an obvious offset in the bedrock stratigraphy between Discovery Ridge and Treves Butte, suggesting it might be a thrust fault hoisting the Treves Butte granites several hundred meters higher than the contact. Preferential erosion of the fault is what may have produced the gorge allowing ice to flow through. However, through subsequent lowering of the ice sheet, it appears as though this little trickle has since shut off, resulting in the stagnation of where we found the ice-cored moraines. All that remains are some impressive crevasses being inundated by large wind-scoops.

The concentration of debris through the sublimation of the ice seems to have preserved ice underlying the areas of the thickest debris accumulations. The resultant structure is a preserved ice-cored ‘crest,’ which we take to suggest the minimum thickness of the ice sheet when the first bits of debris began to emerge.

Guided under these premises, we decided to take samples on the crest, and towards the base of the moraine. The crest samples might suggest the age at which the ice-sheet stood at that elevation, and the lower samples would reveal the inherited component of the cosmogenic nuclides. Since they are just emerging, they should have an exposure age of zero – thus allowing us to calibrate the crest samples by subtracting the ages given by the lower samples.

A typical sample was collected by selecting an erratic based on the following criteria: First, the mineralogy must be such that there will have been production of cosmogenic nuclides. In this case, the quartz from the granite is useful for detection of 10Be and 26Al (from spallation reactions with silicon and oxygen, respectively). Also, mafic minerals, such as clinopyroxene and olivine from basalt, yield 3He, which is useful for determine exposure ages. In the case of the Discovery Ridge moraine, we sampled primarily granites, since there were very few mafic rocks to be found. Basaltic cobbles from the tillite were sampled, though sparingly – due to the possibility for prior exposure after deposition in the late Permian.

The second consideration for selecting an erratic to sample was to find rocks that appeared not to have prior exposure. Supraglacial rock-fall derived debris often times includes portions of exposed cliff faces, which under cold-base glaciation may have been exposed for long periods of time before eventually falling onto the ice. Therefore rocks with heavily weathered (rounded, cavernously weathered, exfoliating) faces were avoided, and the most angular fresh-looking subjects preferred.

The third consideration was to select erratics that have not been translated or rotated since deposition by the ice. For this purpose, large rocks that would not easily slide were generally preferred, and rocks located in frost-patterned karsts were avoided. Perched boulders were preferred, since it is unlikely that any other process could have placed them in such precarious positions.

Other considerations were certainly made regarding rock shape, and just the ease of actually knocking a sample off of them. Rocks with flat tops were preferred, due to their maximum exposure to the skyfield. Samples were always taken from the tops of boulders, to minimize the effect of shielded parts of the large rocks.

Then, since we were working in an area surrounded by large escarpments, we had to account for the amount of shielding from cosmic rays by the mountains. Shielding corrections were made using a Brunton compass and a Suunto clinometer, where the inclination of the various peaks was measured with the associated bearing.

Once the sample was selected, and the shielding correction made, the elevation and position of the erratic were recorded. The length, width, and heighth of the boulder was quantified, and the sample was photographed with a scale once up close, and once within its surroundings. After the measurements, we proceeded to collected a substantial sample for later analysis by bashing it with a rock hammer! The sample was then bagged and tagged, and it was off to the next. We generally sampled at least three rocks per location, trying to select multiple lithologies if possible for age comparisons and calibrations.

In addition to sampling the rocks, I had the divine privilege of operating the Trimble differential GPS unit. This is quite the instrument, as it provides millimeter scale precision for location, and centimeter scale precision for elevation. The unit consists of a base station which we set up at camp, and constantly logs data with a stationary antenna. In the field we use a roving setup which initializes with the base station, and remotely collects data points and continuous transects. For the Discovery Ridge moraine, I collected a topographic profile both on the longitudinal and transverse axes. I then collected data points for each sample site. This data will be useful in reconstructing the profile of the moraine, and then relating the ages of the various samples with the associated moraine elevations… These ice-cored moraines are tricky, so we definitely need to use every possible method to figure them out!

So ends the sampling diatribe. Sampling, beyond the technical scheme of things, can be an adventure. Today, a stiff, cold wind blasted through the gorge, and rendered my hands useless without thick gloves. So I operated in spurts of writing and measuring shielding until I could no longer move my fingers, warming them up again, and repeating the process. Needless to say, what would normally take a few minutes took a bit longer for all of us today – but the body adapts, and learning ways of blocking the wind definitely made the situation more physically bearable.

We sampled until about 1800h, and raced back to camp for dinner. Pete made a delicious spaghetti with sausage sauce, which was quickly devoured. The bedtime exodus shortly ensued, and hopes for more exciting adventures in science tomorrow propagate through my mind as I drift off to sleep. Bless bless.

Stuck Between a Basalt and Hard Place

Today was marked by a normal beginning, with a breakfast consisting of corn-beef hash (at least for myself) and raisin-filled brown bread. Once everyone had emerged and fed, we set off east across the ice towards Treves Butte with the intention of sampling a basalt dyke which vertically cross-cut the granite cliffs. Theoretically, a transect of exposure ages up this dike may reveal a rate with which the ice sheet lowered. The clinopyroxenes in the basalt would allow us to utilize small samples for analysis at Sujoy’s noble gas laboratory for quickly obtained, reliable exposure ages. Thus, these dykes cutting Treves Butte were ideal for the reconstructing previous ice elevations.

We took the snowmobiles to the edge of the ice-cored lateral moraine abutting the cliffs of Treves Butte, and discussed sampling strategy. I inspected one of the dykes, which required cramponing up a steep snow slope to the base of the first dyke of interest. The basalt cut through a very steep granite face, and differential weathering provided a narrow crack through which to climb and access the basalt at different points. It quickly became clear that this was not going to be as easy as it appeared from afar… What from a distance looked like quaint little cracks and jutting rocks to use for scrambling, turned out to be precipitous nearly vertical ledges and overhangs a bit closer up.

The group decision dictated that Peter and I would attempt to sample the dyke I had inspected, and Sujoy and Robert would sample another that was angled a bit more to the horizontal. I took a base elevation using the Trimble differential GPS, and calibrated the altimeter to that spot, as it wasn’t going to be possible to get elegant GPS points on the climb. Peter and I ascended the snow slope, and reached the basalt base where we took our first sample. The basalt proved to be a worthy adversary, as it took us the better part of an hour to wedge out a piece. Meanwhile, the wind began to blow fiercely around us, pushing a seemingly endless series of stratocumulus clouds across the sky towards the west.

Finally having finished taking the first sample, and its associated shielding correction, Peter and I ascended the narrow, nearly vertical gap between the granite and basalt. A thin strip of snow funneled into the gap required the use of crampon and ice-axe, as well as jutting basalt for holds and leverage. We kept trucking up this incredibly steep crack in the rock, until I realized Peter was almost suspended directly above me. I declined to look down at this point, afraid it would make me a bit weak in the knees to see how far down the drop was. Trusting the crampons and ice-axe, with no rope attached, had me sweating a bit… But perhaps the nervousness causing the adrenaline to surge was a good thing, as my hands, with only glove-liners on for increased finger agility, did not get cold amid the wailing Antarctic winds.

The next task was overcoming a lip of snow exceeding the vertical. I reluctantly placed all of my trust in the tools, and made it over. Overcoming the lip also entailed some fears that have always resulted in my shying away from rock-climbing. About time those pesky fears were driven away.

Once above the lip, I climbed, still trusting my footing which at this point was merely the toes of my crampons scratching rock through a light snow cover. I reached for a basalt ledge, and finally had something solid to hold onto. I dug footholds into a small patch of firmer snow with my crampons, and stood fast. I gathered the courage to look down, and the view was spectacularly intimidating. Where were we going to go once on top? How would we get down? An added worry then presented itself, as my warm mittens that had been stuffed in my jacket pocket, were visible about 10 meters down inside a narrow crack where they must’ve dislodged themselves from my pocket.

By this point, sampling was out of the question, as we found ourselves literally between a rock and a hard place. I looked up at Peter, who seemed to be stopped as well, and asked:

“What do you think?”

The question came out from an intense stream of consciousness pouring through my mind, and when asked after a long silence, in any other situation, would have been perceived as vague at best. However, as if reading my thoughts, he replied:

“Well, at the moment I am not very happy about this…”

He looked down with a nervous smile, and added:

“You seem to be handling this better than me!”

I must have been withholding my fears, because with my lack of experience in such matters, I admit I felt a bit frozen – apprehensive that going up or down would have a safe outcome. Hearing that Peter was also uncomfortable with the situation made me on hand feel good that I wasn’t overreacting to the situation, but on the other hand even more nervous, because my highly experienced mountaineer friend did not like the situation. But the good feeling outweighed the bad, because I knew Peter would have a trick up his sleeve.

Discounting the possibility of a sample (though in retrospect, it would have been a crowning achievement), we discussed the possibilities. One alternative was to exit the dyke’s gap, and climb down the granite. This appeared very dangerous, as the granite was composed of steeply dipping joint faces, which did not favor good traction even with the best vibram rubber, and were smooth, without notch or crevice to hold onto. We discounted this possibility, as even getting onto the granite face entailed removal of the crampons, which did not seem possible.

The next alternative was to just keep climbing up, hoping that an escape route would become evident. This was a gamble, and getting all the way up was an uncertainty in itself. At this point, the best option was to down-climb what we had already ascended. This was tough to convince ourselves, since down looked like the most menacing options.

We roped up, and Peter rigged a belay with two snow stakes as anchors, and I began to climb down. The cold wind, and my cooling hands were a prime incentive to descend, however, overcoming any hesitation. The feeling of the rope reinforcing my weight certainly provided confidence, and retrieval of my gloves had me immensely enjoying the descent. The length of the rope ended a few meters above the bottom, but in a place where I could stand without fear of falling a great distance. Peter then belayed himself while I stood still attached at the bottom. I had to climb a few more meters up, so Peter could arrive at a safe place to unhook. Ahh – safe!

Unfortunately, we had to leave the anchors and karabiners on the cliff as a sacrifice to the Gods. I suppose we are following in the tradition of Mercer though instead of leaving tins to become incorporated into the till, we have left climbing artifacts. Though I hope this incident does not repeat itself,it will still make for a good dinner-time story to perhaps overshadow the fact that we only made out with one legitimate sample! I guess Antarctica has its limits concerning how much of its rock it is willing to give to us. Fortunately Robert and Sujoy were more successful with their dyke, which will hopefully tell an equally interesting, but much more useful story…

Darling Ridge Moraine Complex

Today we visited the moraine complex west of Darling Ridge, where several alpine glaciers flow onto the ice sheet from the cliffs. I arose just before 0700h, and boiled water for hot drinks and oatmeal. I fried some brown bread in the skillet for the others who arose around 0800h.

We set off shortly thereafter, and I had the amazing privilege of being towed in the sled behind the ski-doo. We have three ski-doos for four people, and it was my turn to endure the sled ride rather than driving. The ride was long, and quite bumpy. For about two hours (due to putting in a flag route) I clenched the sides of the sled as Robert towed me over sastrugi and crests of blue-ice. Daunting crevasses passed underneath (at least from my inexperienced perspective they were daunting), and the wind scoured the outer layers of exposed skin. Twice, Robert stopped to take a picture or something, so I had ample opportunity to dismount my humble transport and stomp my feet to restore circulation… And, twice, Robert hopped on the sled and took off without looking to see whether or not I was on board. So, twice I ended up comically yelling, flailing my arms, and chasing after the snowmobile trying to get Roberts attention. How absolutely amusing it was for the others to watch (luckily someone noticed I was being abandoned)! I think Robert was mesmerized by the moraines in the distance, and drawn to them as one might be drawn to siren song.

Once on the moraine, we ate lunch and then sampled large, angular granite erratics from the outermost moraine of the complex. It appears as though this moraine was initially deposited by supraglacial processes on the nearby alpine glacier to the east on the ridge, and molded by the westward flowing ice sheet.

We sampled along the moraine ridge, and lower on the ice – the same strategy as used for the Discovery Ridge moraine. After sampling a cross-section and collecting a GPS topographic profile, we headed back. I sacrificed myself to the altar of the Siglin Sled once more, and we returned (the return trip was quicker due to the established flag route). I covered the ski-doos, consolidated the samples, and filled the stoves for Mexican night! Burritos were made, and followed by a dessert glass of Glenlivet. Though the sled rides were admittedly a bit rough today (however less so than I above stated – the language was merely for dramatics, and I deserve – nor expect – any sympathy), they were far outweighed by the majesty of the landscape I had to occupy my mind. The weather was clear and beautiful, without a single lenticular atop Mount Glossopteris or Mount Schopf. We are certainly blessed to have days a gorgeous and productive as this.

January 6, 2005

The Treves Butte Moraine

Yet another day of sampling (I suppose, if we are lucky, this will be a common theme for every journal entry), however we lost our bluebird weather. The wind crept up to about 16 kts, with gusts of about 30 kts. Everything around was a bit dim, with a thin veil of clouds overhead. I awoke this morning to the tent flapping, and went to find Pete was already up… He beat me! Luckily, he hadn’t made anything yet, so I had something to do.

We set off back towards the moraines near Treves Butte and Discovery Ridge, bypassing the trip out to the Bennett Nunataks on account of the flat light impeding the surface definition needed for identifying crevasses. Today I got to drive a ski-doo, an opportunity which I welcomed after yesterday’s endurance trip in the Siglin. We arrived back at the gorge between Treves Butte and Discovery Ridge, and chose to sample the moraine on the Treves Butte side (probably the northern continuation of the ‘Discovery Ridge’ moraine, with the midsection covered by snow blowing through the gorge). Before lunch I sampled a basalt cobble that was cemented into a tillite boulder. Noticeable cubes of clinopyroxene could be viewed with a hand lens, thus providing great material for using helium to derive an exposure age. Hopefully the cobble is derived from lodgement, which supposedly was never previously exposed. To think that that boulder was glacially abraded, transported, and then deposited way back in the Permian, and then sat around for millions of years, and then was picked up again, and redeposited in a till composed partially of tillite!

We hammered away for a while longer, until the wind finally convinced us it was time to go back to camp. The number of samples should be sufficient to constrain the ages of the ice-cored moraines near Discovery Ridge. Once back at camp, I cooked a steak dinner. I cooked the steak over a low heat in a pan greased with butter and dehydrated onions, and sprinkled the meat with salt, pepper, garlic powder, basil and parsley. Everyone seemed to prefer medium steaks, so I tried my best. I accompanied the entrée with scalloped potatoes cooked with mozzarella and Monterey jack cheese, and sautéed vegetables. It was a simple meal, but it sounded like the scientists enjoyed it (or at least said they did). A data-entry session with Sujoy followed, and it was off to bed. We all eagerly anticipate venturing into the Bennet Nunataks region to see what surprises lie in wait…

January 7, 2005

Evidence of a Permian Glaciation – Discovery Ridge Terraces

Another day in the Ohio Range, yet chock full of new ideas and experiences. The weather was rather calm, temperature about 0 degrees C, and the warm wind in the morning around 11 kts from the east. The visibility was still poor, with the ridges obscured in cloud, so we were again bound for Discovery Ridge. Instead of sampling ice-cored moraines, however, we climbed up to the granite/sandstone terrace in the Discovery gorge.

To access the terraced bench, we took the ski-doos as high as possible on the snowslope adjacent to the cliffs. With crampons on foot and axe in hand, we ascended the snowslope which brought us to the granite terrace. The bedrock granite looked significantly more weathered than the angular erratics seen in the moraines, and appeared to have been subject to wet-based glacial abrasion! The surface was very similar to what one might see on the stoss side of a roche moutonee in coastal Maine! Moreover, the ramp seemed to be on the lee side of the current ice flow, suggesting that the ice responsible for scraping and smoothing that granite was flowing the opposite direction, from west to east. A smattering of granite erratics lay perched on the bedrock surface, and the freshest looking rocks were sampled. It is my hunch that these erratics represented the oldest and most extensive ice-sheet elevation (perhaps from the Penultimate glaciation?)… Hopefully the samples will reveal this…

The view from the Discovery Ridge bench was spectacular! The vertical granite cliffs soar hundreds of meters into the air, and alpine glaciers flow into the ice sheet, with blue-ice zones revealing looping debris bands. Additionally, the ridge has a fascinating sequence of Permian sedimentary units comprising the Tillite sequence. Following the outcrop up the ridge, I noticed the glacially abraded granites topped by a cross-bedded sandstone unit. I believe the granite and the sandstone may be pre-Permian, as the sandstone was terraced and appeared abraded as well, followed by a sharp unconformity between it and overlying diamictite. The lithified diamict was likely a tillite because it was full of striated cobbles. The thin layer was then topped by a coarse-grained sandstone with pinched bedding suggesting lithified braided outwash (or deltaic sediments?). The sandstone then graded into a massive, shale outcrop with many inclusions of small pebbles and large cobbles. This, to me, appeared to be a massive marine mud full of dropstones. Sujoy agreed that it was a lithified aqueous deposit, but questioned whether or not it was marine or lacustrine (based on the assumption that Gondwanaland glaciations were primarily interior continental glaciers that didn’t necessarily see the ocean). Robert disagreed altogether, suggesting it was a lodgement till, based on the massive matrix.

Following the outcrop a little further up, another thin layer of braided outwash sands could be seen, followed again by the controversial massive diamict. In order to resolve this controversy, I followed the unit a far as I could before the others looked restless for dinner, and discovered that the unit graded into rhythmic laminae with layers deformed from the dropstones. So, I remain steadfast behind my hypothesis that it was an ice-proximal marine environment grading to distal (with the interruption of braded sands possibly indicating a small advance?). Margaret Bradshaw’s work also mentions permo-carboniferous fossiliferous marine sedimentary rocks topped by terrestrial shales and coal (which we will see at Mercer Ridge, I expect), indicating a very similar glacio-marine stratigraphy to sub-marine limit Maine (which, of course is only 12,000 years old, not lithified, with terrestrial living organics instead of coal)! I think the Permian ice denuded the granite and sandstone, deposited a thin layer of basal till, deposited coarse sands (possibly due to high discharge), and then as the ice edge retreated, a proximal high discharge deposited the massive marine muds. Calving icebergs contributed dropstones, and then an advance deposited another layer of the coarse sandy material from an increased discharge flow regime. With further retreat of the ice, sedimentation began to represent an increasingly more distal environment, with preservation of rhythmic laminae and marine fossils. With isostatic uplift, the shallow marine environment then became terrestrial, home to the Glossopteris flora.

Just a little story woven from a glimpse at the Discovery Ridge rocks. Perhaps this region was once the coast of Gondwanaland, maybe not too dissimilar from coastal Maine! It will be interesting to do a more thorough examination of the bedrock literature of Margaret Bradshaw, and see where my hypothesis stands.

After scrambling around on the ridge until 1900h, we became sucked into a snowy sphere of visibility (or rather, lack thereof). We slowly found our way back to camp, rattled by the jolts of sastrugi rendered invisible by the null depth perception in the ambient light. I must say, however, the pure white snow drifting across the glowing blue ice was quite spectacular.

So after a quick dinner, it is off to the sack. With hot water bottles keeping my feet warm, and a reorientation of my sleeping arrangement keeping my head above my feet in the constantly changing sub-tent snow/ice topography, I have to think that this is the epitome of life and comfort. Who would have thought such things could be so readily obtained in an environment known for its absolute harshness? I surely am not one to complain.

January 8, 2005

The Tuning Nunatak, pt. 2

Today was a gorgeous one – a bit different than the last few. There was no semblance of a breeze, and temperatures were soaring just over freezing! However, the beautiful weather hadn’t fully arrived until midday, when we had already ruled out the Bennett Nunataks. Instead, we went back to the Tuning Nunatak, which again proved itself to be an amazing place to spend such a day, and yielded some interesting discoveries.

The bedrock surfaces were similar to what we saw on the Discovery Ridge, with beautifully abraded surfaces and plucked faces. Chattermarks and lunate gouges appeared preserved in the granite surface with profile symmetry suggestive again of eastward-flowing ice… Here was another outcrop with an ancient glacial surface showing ice-flow heading the opposite direction (and wet-based, which is not characteristic of the Antarctic Ice Sheets today or in recent ice ages).

We found a series of bedrock terraces on the north side of the mountain, all of which appeared to be related to this old glaciation. The nature of the terraces was interesting in that they had perched erratics all the way up, and seemed to represent periods of stability when a portion of the terrace would fracture off and be conveyed away. This may have created the step-like system of terraces, however it may be related to a much older glaciation than the erratics we sampled on the surface. Our exposure ages will hopefully shed some light on these structures.

We sampled a transect of erratics up the system of terraces, using the altimeter calibrated to the Trimble at the top to record elevations. We then called it a day, and I got to ride the sled and view the monstrous Darling Ridge the whole way home. Unfortunately, a slight breeze had perked up coming from the west (180 degrees from the prevailing wind direction), and it seemed to be going the same velocity as the ski-doo towing me. Therefore, I ended up a bit nauseous from the exhaust I was breathing the whole way back. But the day was still to die for, and the weather still has not changed. I took some pictures which I hope will capture even a fraction of the beauty of this escarpment, and truly enjoyed scrambling around on Tuning Nunatak. I even cinematically captured Peter ‘trundling’ a rock over the edge of the cliff onto the snow-slope and down to the ice – certainly a moment of comical mischief!

January 9, 2005

The Bennett Nunataks, pt. 1

Finally, we were able to reach the Bennett Nunataks today! After a Sunday brunch of re-hydrated scrambled eggs and bacon, we set off on another beautiful, windless, warm day. We drove for quite a while to get to the nunataks, arriving first at the northernmost peak. Since there were three nunataks comprising the Bennett Nunataks, we named them ‘Mama,’ ‘Papa,’ and ‘Baby’ Bennett Nunataks. ‘Mama Bennett,’ the northernmost, was completely encircled by a steep, deep bathtub-like windscoop – thus requiring some caution and safety gear to access. There is one ice-bridge gaining access to the rock, but it turned out to be a shear knife-edge – not conducive for walking across.

We decided then to check out the other peaks, ‘Papa’ and ‘Baby’ Bennett, before spending all day getting onto to ‘Mama.’ ‘Baby’ Bennett was easily accessed, and was the chosen lunch spot. This nunatak was merely a small outcrop poking out of the ice, nonetheless having perched erratics useful for dating. However, a group of people had obviously visited this spot before, as a trash heap was exposed from a sublimating crevasse edge. Coors cans from the 80’s, old car batteries, cans of Coleman stove fuel, bamboo poles, Christmas wrapping paper (apparently “To: Eric”), and fish meat comprised this garbage deposit. Obviously someone thought it clever to dump it down a crevasse, probably assuming nobody would ever witness that spot… I wonder if Eric would be surprised to receive his discarded wrapping paper back, after all these years.

We quickly organized the trash for later transport back to camp, and headed off to ‘Papa’ Nunatak (the southernmost of the Bennett Nunataks). Access was easily gained, as the windscoop was minimal on the southern side, but ascending the peak was more tedious than it initially appeared. There was a shear cliff on the eastern face, and an extremely steep snow-slope on the western face. In a few instances I found myself perched precariously on a narrow ledge trying to round a granite face with only the ice at the bottom of windscoop to break my fall. The loaded heavy pack certainly complicated these instances as well! But, I must admit I had a fantastic time finding my way up the Nunatak.

The weather remained incredible, making the sampling a joy. We found perched granite erratics all the way to the peak, which was accessed only by crawling through caverns weathered from the bedrock. Robert and I took samples at the peak, enjoying the fine view of Darling and Lackey Ridges. Peter and Sujoy in the meantime left for ‘Baby Bennett,’ to sample rocks that didn’t appear to be anthropogenic in placement. Robert and I finished the transect, and headed down with packs full of granite. Thankfully, I had gone up and down the mountain about three times in the afternoon taking GPS positions and profiles, so I felt comfortable with the route. We got to slither back through the caves and cracks towards the bottom, when we noticed some cavernous weathering in the granite which resembled the head of a troll (or perhaps a lizard monster)! Three holes for the eyes, and a large gaping hole with ridges forming the menacing mouth and teeth, definitely were suggestive of an ancient, petrified mythical creature. Robert insisted that I crawl into the gaping mouth for a photograph. I managed to scramble up the face, and climb in the mouth, where I posed as a hopeless victim satisfying the troll’s appetite.

I crawled out of the troll mouth, and we headed to meet the others back at ‘Baby.’ We loaded the trash into the sleds, and made the long ride back to camp. A quick and tasty pork chop dinner replenished the nutrients and fat lost during the days adventures, and it was off to bed around midnight. It will be exciting to see if we cannot determine a rate of ice lowering from the Papa, Baby, and Tuning Nunatak transects! I wonder if they will correlate, and what the effect of the wind-scoop is…

The East Darling Moraine and Weather

Today started off somewhat clear, with a stiff breeze blowing from East Antarctica. I was up, got the snow, made hot water for the others as they emerged, and scraped off a drift that had formed in the entry to the cook tent, so the others needn’t wade.

We ate breakfast, and set a date for our camp move with AirOps via the Iridium satellite phone (we plan on being ready to move to Mercer Ridge by the 15th, if all goes well). Then we were off, it being my turn to ride on the sled. I suppose I am lucky in this respect, as being the lowest on the totem pole, there was always the possibility that I would constantly ride on the sled! Thanks to an understanding, merciful crew! Some adjustments to my attire rendered me entirely wind-proof, however. One can be entirely unaffected by wind if you put on your windstopper hat, tie the ear-flaps, then pull down your neck-warmer over your inner hat to secure it. On comes the Icelandic wool hat, and that is secured by the ski-goggles. Utilize the optional wind-breaker hood, zipped-up all the way, and no wind will penetrate! It turned out that this get-up would be put to the test later in the day…

We traveled to the first moraine we had viewed from the ice on January 2, located just south of Tuning Nunatak. Robert and Peter went to sample a bench that diagonally traversed the cliffs of Darling Ridge, hoping to find evidence for the maximum ice sheet elevation. It appears as though a bench has been carved along a joint plane all along both Darling and Discovery Ridges, thus suggesting it may have been exploited by ice. Other parallel joints could be seen above and below, but none had been excavated to the point where they formed such a bench. Sujoy suggested that this may be a sort of trimline, representing the maximum stable ice-sheet elevation. Similarly, a darker reddish color of the granite above the horizontal joint suggests it has undergone more weathering – a subtle indicator of a trimline perhaps?

While Robert and Peter were scrambling around on the cliff terrace, Sujoy and I sampled a transect through the moraine below. We sampled the crest, as well as the rocks just emerging through the ice, presented with many nice, angular erratics fitting our list of criteria to a tee.

Over the course of the afternoon, the weather began to deteriorate. Sujoy and I were blasted constantly by wind, and receiving blows from stronger and stronger gusts as time drew on. It is not easy to pin down a sample bag for a picture when the mighty wind keeps trying to whisk it off to West Antarctica! Also, every time you go to take a picture, it is as if the wind knows this, and gives you a push in some sort of playful, yet mischievous manner that makes work difficult…

When finally finished sampling, everyone regrouped at the moraine feeling quite cold and windblown. Climbing out of the windscoop, we discovered our snowmobiles half drifted in with blowing snow, as they were in the main path of the howling freight-train of wind… We dug them out, and had to perform quite a juggling act to make sure no gloves flew away while tightening up the ropes on the sleds.

We quickly got moving, but the surface definition was extremely poor so sastrugi and crevasse alike were invisible until one was perched atop the structure. I felt bad for Sujoy, who had to endure the sled ride back, with me pulling him blindly through the storm!

The wind crept to its final, constant velocity of about 30 kts. Of course it isn’t blowing the tents over, and one can accomplish a certain amount of necessary work in it, but it definitely has a tendency to take the heat right out of you. I again cleared the drift in front of the Endurance tent upon our return, and by the time we were eating supper, the drift had completely reformed…

Looking around outside during the windstorm, you could actually still see all the ridges, and further. Visibility was only obscured by low, drifting snow, however it was all snow merely being redeposited. No precipitation was occurring in this event, yet snow was certainly being focused in new areas. This makes me wonder about ice cores, and if they may be obscured by such focusing events… Regardless, the storm was actually very beautiful and intense.

Moments from today allow me to see an infinitesimal portion of the immense power of the Earth… I now count myself a firm believer in animism, and cannot help but believe that this landscape is as alive as we are, and more powerful than anything we can contemplate.

Under the Weather, pt. 1

It is just after midnight, so I mustn’t remain awake long writing… I awoke today to the sound of the wind, having not relented from its furious blasts last night. Recalling what Peter had said (“If it sounds like this in the morning, just go back to sleep…”), I took his advice and did just that. I eventually couldn’t sleep any longer, and was up and about at 0930h. I arose, shoveled the drift from in front of the cook tent, reinforced my own with a fresh anchoring snow-pile, and dug up some hard-pack for melting. I made coffee, hot water, and still there was no sign of the crew… I decided to go for it, and made breakfast.

I fried up some raisin-filled brown bread, sausage, and threw some de-hy scrambled eggs into the skillet. In order to spruce up the re-hydrated eggs, I added some Monterey Jack cheese, basil, and parsley. The eggs now at least looked bearable, and I had everything assembled and ready to be delivered as breakfast in bed for my cohorts. Unfortunately, Robert entered the tent just then, but I was able to serve Sujoy and Peter. I think I may have startled Peter out of sleep, because when I asked:

“Peter, I have a delivery…”

He replied:

“What is it!? Oh, oh – okay…”

What, other than food, he thought I was delivering was beyond me – but he later told me that he thought the Twin Otters had arrived and left while he was asleep, and they had left a delivery for him! I can now understand his startled response.

By around 1300h, we were no longer under the weather, and decided to brave the residual winds and sample the topmost terrace on the northern Discovery Ridge. It was very cold and windy, however still an amazing sight on the tillite. Because of the environmental factors, sampling was certainly very quick and efficient! On the way off the table we could see the wind blowing magnificent plumes of snow from the cliffs overhead. A hydraulic formed in the air just above the ridge where large clouds churned over themselves – quite amazing to see what happens when air masses that have been cruising across the flat ice sheet hit the cliffs of the Ohio Range!

Our return was quickly followed by dinner, where we discussed a camp move in a couple days. The plan for tomorrow is to get back to Mama Nunatak and try to get onto the outcrop from the windscoop, and then start preparing the camp for a move. We’ll see if the weather permits (both down here AND on the Buckeye Table).

January 12, 2005

The Bennett Nunataks, pt. 2

Today was our last day of fieldwork in this portion of the Ohio Range, as tomorrow we are to pack up camp for the move to Mercer Ridge. Essentially, our fieldwork is 2/3 of the way done. There are two series of moraines on Mercer Ridge that will take us around three or four days to sample (provided the weather cooperates).

It is almost a bit sad, as today we saw our last glimpse of the Darling Ridge moraine complex, and the Bennett ‘family.’ Today, due to the perfect weather, we headed back to the Bennett Nunataks, where Robert and I would attempt to sample ‘Mama’ Bennett, and Pete and Sujoy would finish up ‘Baby’ Bennett.

Pete belayed Robert and I down the deep, icy windscoop where Robert and I were to spend the day. We found a way up to the summit, where we were treated with a fantastic view of the other Bennett Nunataks, Darling Ridge and the moraines, as well as the large ice-falls to west.

We sampled from the top down, where I took a Trimble at the bottom to calibrate Robert’s altimeter. It was a fine day for fieldwork that was for sure. Pete and Sujoy arrived just as we were finishing up, and Pete belayed us we climbed up the windscoop with crampons and axe. That was an interesting experience, as I was climbing with a pack full of rocks, food and drink, with the Trimble pack strapped on… I wasn’t keen on hanging out on the steep ice for long, so I trudged up at a brisk pace. Peter was having a hard time keeping up the belay rope, so I had to periodically stop and wait for the rope to become taught again. Eventually I reached the top, and Robert climbed up. We packed up the gear, threw it on the snowmobile, and were off back home for the final time from this particular area.

Another day, another meal, and here I am. I welcome a change of scenery, and look forward to being on the table – however I feel extremely blessed to have had such an incredible experience in this part of the Ohio Range. Let us hope that Mother Earth blesses us with a similar experience in our new home.

Building the Runway, and a Brief Run Away

Another beautiful, balmy day in the Antarctic… perhaps this whole “Global Warming” (or, as Sujoy would say, facetiously: “Remember, not global ‘warming,’ global ‘climate change’”) thing isn’t so bad. I arose to a fantastic brunch of blueberry pancakes, bacon, and cream of wheat, and got to work organizing camp for the move now to be on the 15th. I organized our samples into 10 rock boxes under Sujoy’s guidance. We organized the samples in a way which did not concentrate entire field areas into single boxes, but rather spread everything out (this actually worked out well when organizing by sample number) so if a box was lost, not all samples from a specific site were gone.

After organization and a quick lunch, I set out to work on the runway for the twin otters. I chopped down the sastrugi with a shovel, and Sujoy came by with the Skandic and smoothed things out. At one point, he gave me a lift to the opposite end of the runway, but I wasn’t well situated while the machine got going. I felt myself begin to slip, and before I knew it, I was tumbling around on the surface of our new runway… I personally got to assess what it was like to land on the surface, and must say, it was still a bit lumpy! I recovered from the tumble and chased after Sujoy, who had just noticed that something was missing from the Skandic… We had a good laugh at dinner recounting the comical incident. Apparently Robert had been watching literally moments after the incident… if only he had looked sooner, he would have been treated to a spectacularly goofy show!

After sastrugi decimation, I got an okay from Peter to go for my first run on the continental Antarctica. I ran along the sled trail towards the blue ice near Treves Butte. It was my first run in about two weeks, and felt truly amazing. How I’ve missed the zen of running! I wish that I could’ve kept going and going, with no particular destination. I returned, the round trip being about 8 miles, warm from running in the sun, and did my push-ups. I found from my return to exercise today that I was not as out-of-shape as I thought I’d be.

Our dinner this evening was pork sautéed in Thai peanut sauce with wild rice, and decadently prepared frozen veggies (Sujoy’s obvious gift). We had a cup each of egg-nog with some glenlivet to celebrate the successful completion of all field objectives for the lower field camp. Now it is off to bed. Robert hopes to explore the unnamed ridges coming from Schulthess Buttress, on the central Buckeye Table cliffs. Good fodder for hopeful dreams. Sjàmst í morgan…

January 14, 2005

Adventures in Cooking, our First Visitor, and the Unnamed Ridge

Today turned out to be a day off for everyone, as all the work had been completed, and flags pulled. I arose around 0745h, checked in with MacOps, and got the stoves going. Today was a sleep-in day, so I decided to prepare a treat for everyone. I assembled the oven for the Coleman stove, and began to preheat it in its inaugural use for this season. I pulled out the gingerbread cake mix, and prepared the batter. We didn’t have any eggs, so I substituted a cup or so of egg-nog – basically eye-balling the amount, thinking: “oh, that looks like about two eggs-worth!”

I added some extra flour, as per the high-altitude cooking instructions, poured the batter into two 8×4” pans, and threw them in the oven. Realizing that just gingerbread cake would not be enough, I whipped up the cheesecake mix for use as frosting. The cakes baked nicely at about 350 degrees F for about 40 minutes, and knew they were done when I stuck a matchstick in the cake, and it emerged with no glop. When the cakes were hot out of the oven, I glazed them with the cheesecake. They were now ready to serve! The endeavor appeared to be successful, as everyone enjoyed the cakes (or at least were polite enough to pretend).

As the cakes were just out of the oven, we had a visitor! Our first glimpse of life beyond each other occurred when the gingerbread smell was strong and wafting about the camp… A skua! The bird swooped by and nestled down on some sastrugi just outside of camp. It must’ve been a long journey, but perhaps the carnivorous gull has discovered a camp-to-camp route leading towards the Pole. So, against all Antarctic environmental regulations, we threw the wayfaring stranger a leftover sausage. The skua didn’t move, and just continued to eat snow and pick at wind-blown gravel. We went back to the gingerbread meal, and the next time we looked, the skua had left. We retrieved the sausage, which the skua had bitten in half, but surprisingly had not devoured. I guess the skua was expecting higher class accommodations. To refuse a hardy sausage this far away from any food! Perhaps the skua knows something about this land that we don’t…

After breakfast, Robert and I took the Skandic and a Tundra out to an unnamed ridge spurring off of Schulthess Buttress, forming the eastern edge of Ricker Canyon. We basked in the blazing sunshine, and practiced self-arrests on a steep but safe snow-slope. We then began our hike up the ridge, which was another one of these dramatic knife-edges. There was a shear cliff on the east side, and a steep snow-slope on the west. The snow-slope was so steep that no ice-axe would stop you from careening a few hundred meters to the ice sheet, so we had to be careful when crossing the icy parts of the ridgeline.

The form of the ridge appeared to be a very steep stoss-and-lee form, with the west face appearing very similar to the other abraded bedrock surfaces we have seen around. The east side was vertical, and in some cases overhanging, cliff – thus the plucked, lee-side of the ancient glacial landform. Classic example really, and agreeing with the other landforms suggesting wet-based ice flow to the east, as opposed to the current westward flow direction. Here we had possibly another relict Permian landform, perhaps never having seen human footprints.

We took two bedrock samples, but saw surprisingly few erratics – none of them blatantly glacially transported… Perhaps the ridge was protected by the escarpment from full-on ice-sheet flow unlike the exposed outer nunataks. All in all, our purpose was more to climb and see what we could see than anything else, and that we did. We reached a lower peak on the ridge, and declined to head for the top of Buckeye Table due to a tasty dinner awaiting us. So, we climbed back down and reveled in not having to wear hats, gloves, or really any outerwear.

We returned to camp just in time for dinner, which consisted of delicious roasted Cornish game hens (Peter’s artwork), potatoes (which I got to prepare), and delectable veggies (which Sujoy prepared). Very tasty, with a compliment of red wine and a toast to a fantastic field camp! So far, job well done!

January 15, 2005

Delayed again today. The twin otter didn’t arrive today due to their predicting bad weather for us, when in reality it was a beautiful day. I ate breakfast around the usual time, and moved things into a pile to be easily tossed into the plane (still anticipating a camp-move). When informed of their not coming, I decided to go for a nice, long run to enjoy perfect, sunny calm. I ran out to the blue ice near Treves Butte again, and did my push-ups. After a lunch of corn-beef hash, I adjourned to my trusty mountain tent.

I spent my time re-reading the proposal and Mt. Waesche paper, trying to get a sense for exactly which objectives we have left on Mercer Ridge. I took a brief nap afterwards, awoke, and got ready to get out of the tent. I couldn’t for the life of me find my hat, which couldn’t have gone far. I searched my tent through and through – baffled, because there wasn’t much clutter for it to disappear into. I then came to the ridiculous realization that I was WEARING my hat the whole time! Ah, sometimes I wonder how I’ve survived on this planet as long as I have.

The evening meal was Mexican again – and I remembered to break out the canned black olives for an extra treat. I hydrated and warmed up the refried beans, throwing a little Monterey jack cheese in the mix.

Hopefully tomorrow the otter will arrive, however it is unlikely at it is Sunday, and they generally don’t fly on Sundays. Oh well, I could imagine much worse places to be stuck… like LAX! I will winter-over here before I find myself stuck for more than 24 hours in that place.

The Sunday Rule, Camp Recipe for Tuna Casserole

Ah, the no-fly on Sunday rule stuck, as again – no otter. It appears as though an effort will be made to move us tomorrow, but if there’s one thing I’ve learned about logistics: nothing’s for certain! And, like many days before, today was a beautiful day. It was a little cooler than usual, with 20-30 kt winds, but we are used to that by now.

I arose around 0930h, and saw Pete in the Endurance tent with ‘no news’ from MacOps. Pete went back to bed, and I fired up the stoves. Pete’s fatigue must’ve been contagious, and with very little to occupy me (as all others were fast asleep), I resigned back to the tent for a while.

When I awoke, the others had gotten up, and Robert made some excellent all-grain pancakes. I scarfed down a stack, and went for a run. My run today was the same 8 mile blue-ice route, but the added wind resistance made it a little more challenging for the first half eastward towards the blue ice. The return run was a joy, however, as the wind pushed me all the way home. I have made it a rule out here to always begin my run against the prevailing wind, so that if some unforeseen thing occurs, I will not have the resistance if I must struggle back camp-wards. Still – not bad! I like our little ski-doo path. I certainly like it a lot more than running the busy roads of McMurdo.

After my run, everyone had again disappeared into their respective tents. This time my kitchen effort was much more successful, as I prepared an improvised tuna casserole. I combined a box of stroganoff mix with a box of ‘herb and butter’ pasta mix, added copious amounts of dehydrated onions, and prepared them according to their combined instructions. After about 15 minutes of simmering the pasta, I added two cans of tuna. After a few more minutes of simmering, a can of sliced mushrooms went into the pot.

While the gruel was simmering in its juices, I took a rock hammer to a load of petrified cabin bread, pulverizing it into little crumbs. The pasta was then dished into two baking pans, with a layer of crumbs and Monterey jack cheese sprinkled over the top. The pans went into the oven, and were baked at 300 degrees F for about 10 minutes, where I tended to the baked beans. I then dished some applesauce into a pan, arranged some peaches around the edge, and sprinkled the whole lot with cinnamon. This pan was placed on top of the oven to receive just enough heat to warm it up.

The meal was received quite well, which I am very glad for. Robert tried his hand then at making brownies, and used egg-nog in place of real eggs. Some combination of factors resulted in more of a fudge soup, but it still tasted fantastic and was highly addictive. I think I prefer Robert’s gooey brownie soup any day over regular brownies. So now for an early bedtime… must be ready for the otter tomorrow, on the off-chance that it actually comes!

January 17, 2005 Delayed…again

“As I walked along the supposed Golden Path,

I was trembling with fear – o the lines and wizards yet to come…

And I see in the distance, silver mountains rising high in the clouds

And a voice from above did whisper

A shining answer from the womb…”

– The Flaming Lips

Today the otter again cancelled for tomorrow… Ahhh…. Yet again, a beautiful day, no transport to our only remaining work site! The irony of it all…

So I went for another run today – just another run, yet one where I was given the privilege of witnessing a landscape largely untrodden by humans, and only seen by a handful of others. Truly I was running along the supposed Golden Path, where all I could see were Ice Sheets and Mountains rising high in the clouds… I could not even see our camp, as the distance I had run across the ice obscured it to a tiny dot amongst the sastrugi. The only visible human influence in my entire view, were the ski-doo tracks we had made.

After my run I read a bit, and then took a nap (the two most popular past-times amongst our crew). I was reading about Amundsen’s depot journeys before his final trip to the south pole, and my dreams were infused with visions of the “Great Ross Ice Barrier” and running sled dogs.

When I awoke, I overheard that the otters were coming to jettison the retro and take Sujoy out to prepare for his classes at Harvard University. After steak night the otter did arrive, and Miles (the pilot) promised to come back the next morning – therefore Sujoy stayed for his last night in the Ohio Range. We toasted to his last night over some Glenlivet, and after some great conversation about all the applications of cosmogenic nuclides, it was off to bed.

January 18, 2005

An Adventurous Camp Move; Sujoy Departs

I write victoriously from the top of Buckeye Table, at our new camp a few miles to the southeast of Mercer Ridge! This is not a victory over nature by any means, as she has treated us very well and was only a bit grumpy today, but rather a victory over the demons of Twin Otter logistics!

The morning again was beautiful, and we received word that the otter had left around 1100h and would arrive by 1300h. About 30 minutes before their arrival, a small lenticular cloud began to form over Glossopteris. By the time they had arrived, the cloud had mushroomed and spread to thickly envelope the entire Buckeye Table… Of course it would happen! After a week of perfect weather and no logistical support, the day we finally got it the weather was bound for a change! Needless to say it was looking grim by the time the otter arrived, but the clouds appeared to be moving fast to the southeast, so we convinced the pilots to wait a few minutes to see what might happen.

Sure enough, a small window of blue opened exactly where we wanted to be – visible from down below. We hurried, scrambling together the rest of our camp for transport. Robert and Sujoy went first up to the top of the table, and Pete and I took down the rest of the camp for the second load. The clouds began to close in again, and it was a long time before the otter returned to fetch us and the rest of the camp. Pete and I were ready to hunker down, thinking we had been left to fend for ourselves by the already nerved-out pilots.

Finally they arrived, looking quite shaken from the first landing on the table. Apparently they thought they had found a good landing spot, but as they neared it, some enormous sastrugi emerged from nowhere and jostled the aircraft quite a bit. According to Robert, after the plane stopped, they were petrified for a moment – and then jumped out to closely inspect the plane. Apparently they hadn’t ever made such a dicey landing, and were almost certain it had resulted in damage to the tail. Robert said that upon the first jostling bounce, they could feel the tail dig in to the snow – which is never a good thing. This explained the absence, and the stricken-white faces of the pilots when they returned to fetch us.

We threw the rest of the boxes, tents, etc. into the otter, and belted ourselves in. We were treated to a dramatic fly-by of Treves Butte and Discovery Ridge as the lenticular clouds careened over the edges… Everything was obscured in and out of murk as we climbed over the edge of the table. A long, low circle revealed the base of Mercer Ridge and Mount Schopf, and the plane was brought down on a flagged-out runway that steered clear of the rollers which had nearly cached the plane on the first landing. The second landing was still rough… I had to tighten the cargo straps while belted in to keep the whole load from shifting and pinning Peter and I in the back of the plane, and had to brace the load with my legs and the virtual free-moving sled on top with my hands. Peter ducked down and braced against the back of my seat which was in front of him, and we touched down. The precautions may not have been necessary, as the second landing was a bit smoother – but seeing the sled and the load lurch towards me wasn’t an overly welcome sight.

The props stopped spinning and were latched up by the co-pilot, and we jumped out of the otter. The second load found itself on our new campsite almost immediately, and the relieved pilots were ready to go. Sujoy had his personal gear plus his sleep-kit loaded into the now empty otter (with the exception of some retro), and we said our goodbye’s. It was sad to see him go, as he was certainly a great man all around – with insightful conversation skirting any topic that may come up, a wonderful attitude, and genuine appreciation for nature and fieldwork. I look forward to seeing Sujoy soon, as Hal and I are to help analyze samples in Sujoy’s noble gas laboratory at Harvard University.

Robert, Peter and I set up camp, and got the grub going. It is noticeably colder today, perhaps that is a function of the increased altitude. We are now living at 2060 meters, a bit over 6,000 ft, which is a similar height above sea level as Mount Washington. However, due to the low-pressure anomaly over Antarctica, the atmospheric and physiological effects are more around 7,650 feet. This is probably responsible for the curious cloud patterns around here, as the cloud stratum occurs quite a bit lower than in New England, where the barometric pressure is a bit closer to the mean.

Now dinner is eaten, and I am a bit tired from the tear down and put-up of camp. I am sure looking forward to exploring this region in the next few days. The bedrock geology appears a bit different than the lower stratigraphy, and the morphology and climate has allowed for the growth of several alpine glaciers on the ridge. It will nice to look at local effects of climate change and these small glaciers streaming from the highlands. It will require a change in thinking from the continental-scale ice sheet, to small sensitivities to local conditions (which are very curious). But now it is time for bed – goodnight!

January 19, 2005

The Mount Schopf Weather Introduces Itself; Flag-route Established; Thoughts on Attachment and Cleanliness

The first day at our new camp was unfortunately a bit relaxed. At 0800h, I was told to go back to bed on account of the 0% snow surface definition. The torturous element, was that we could plainly see Mercer Ridge! But, in order to safely place a flag-route, the definition needs to be good enough to see snow-covered crevasses. So, I dreamed a little more: mostly anxiety-ridden dreams about unfinished schoolwork and financial problems that are (in reality) awaiting me at home.

One thing that I’ve been thinking on recently, is the idea of worldly attachments – and what it is specifically that binds me to ‘home’ in Maine. As Terry Hughes’ ‘Bull-Nye Syndrome’ begins to show its first signs amongst our crew (including me, I’m sure), and the asymptotic end draws near but hasn’t yet arrived, I try to analyze exactly what it is that gives one the itch to depart… When getting down to the necessities, why would anyone ever want to leave this little paradise we have established for ourselves? We have good food, water, warm clothes, and comfortable sleeping quarters. What more does one require? A hot-shower seems nice, but not necessary… It is one of those things that one may romanticize the memory of, and greatly anticipate – but by the time you take the shower, before you know it, the novelty of the greatly romanticized and missed luxury is gone, and you are trapped back in the routine of everyday life.

On account of just the raw fact that one needs to remain clean to remain healthy, I feel as if the dry cold here has a very strong cleansing effect, and the body is able to resume its age-old cleansing mechanisms when not constantly bombarded by products. Even after running, when I feel especially clammy in my windproof outfit, one day of hanging the damp clothes will have them dry and smell-free, ready for use! Perhaps I am deluding myself, and I must acknowledge that over time this property of Antarctica doesn’t hold up, but I am sure amazed at nature’s ability to keep one clean.

The only comfort that I truly miss, and look forward to returning to, is running. A huge part of my life involves simply getting lost both in the world and in my mind, and running everyday to heart’s content. It is my form of soma, keeping me placid, free and inspired.

But all in all, the ‘Bull-Nye Syndrome’ seems to be merely a manifestation of the draw towards samsara and the eternal cycle of suffering. When leaving the ice – who is truly happy at home? Isn’t it all a bit melancholy to return, after the novelty has worn off? I find that at this part of my life, I cannot sit still for too long… I love finding new places to build a connection to, and find my niche that I can make my own.

I digress. We spent the day in idleness, waiting for a clearing that might shed some light on the ground. I tried my hand at being a tailor, and sewed a ‘Scott Base’ patch on my pack – I think I need some more practice.

Peter cooked up a tasty meal of pork and pasta, with Sujoy’s recipe applied to the frozen vegetables. As we ate, the sky cleared a bit, and the southern sun cast a light bringing out the definition on the ground. At 2145h, I suggested we go for it and set up a flag-route while we had the window. There was hesitant, but general agreement. So we set out, and flagged a route to the lower moraines deposited by a cirque glacier on the western face of Mercer Ridge. We managed to get around to the edges of some large, rather anomalous crevasses that stood between the ridge and us. We headed southwards to find the ends of the holes, but had to settle with crossing them where they had narrowed a bit, appearing to be at least partially filled with snow. We were glad we waited for the definition to improve when seeing these large crevasses… They were only distinguished from the rest of the white plain by a slight depression in the snow surface, with smaller sastrugi.

Reaching the moraine, we found it to be fascinating – quite different than the ones we had seen below the table. The lithologies were composed of dark red, weathered dolerite boulders, shales imprinted with the petrified Glossopteris trunks, and various bits of sandstone and glistening coal (or ‘black diamonds’ according to Perstrud on Amundsen’s southern journey). It will be a joy to spend more time on these moraines – the environment is truly spectacular! One almost feels a hint of walking through an ancient forest with the plant fossils and petrified wood everywhere you look!

I collected a stratified sandstone pebble, and a classic coarse sandstone conglomerate, placed them in the ski-doo box, and we were off back home. It is now late (after midnight), and I must arise early to prepare for a day of fieldwork. Ah, finally, back to work – hopefully there will be few idle days waiting to reach the outcrop.

The Lower Mercer Ridge Moraines