Investigation of Historic Coastal Sand Inundation, Shetland UK

Investigation of Historic Coastal Sand Inundation, Shetland UK

Travel Assistance and Equipment Shipping Funding Provided by Dan and Betty Churchill

Expedition Members: Alice Kelley, Joe Kelley, Lee Sorrell

Introduction

This research is a part of The Shetland Islands Climate and Settlement Project (SICSP), an NSF-funded, collaborative study aimed at determining the chronology, causes and extent of sand invasions in the Quendale Links region of south Mainland, Shetland, and archaeological prospection in support of ongoing excavations at the Broo site. Collaborators include researchers from the University of Maine, University of Southern Maine, and Bates College.

The UMaine portion of the research focuses on using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) to characterize dune stratigraphy and locate structural archaeological remains, and the collection of sediment samples for geological characterization and Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating. These results will hopefully contribute to an understanding of the geological and societal impacts of the large influxes of sand that have occurred in the Quendale region in prehistoric and historic settings. The Quendale Links sand invasion is part of a Little Ice Age series of sand drifts that affected hundreds of thousands of acres in Western Europe and British Isles (Clarke and Rendell, 2010). Sand inundation has been noted at archaeological sites in Shetland, ranging from the prehistoric sites of Old Scatness (Burbidge et al., 2001), as well as the historic period sites of Jarlshof (Dockrill and Bond, 2009) and Broo (Bigelow et al., 2005). At Broo, at least one 17th century farmstead and surrounding fields were covered by wind-blown sand, forcing abandonment of what had been one of the most productive areas on the island (Bigelow et al., 2005). An understanding of past events, such as the Broo disaster, will provide important geologic and coastal management information about the causes of climate-related sand invasions on coastal systems.

Funding by Dan and Betty Churchill allowed Lee Sorrell, Department of Earth Sciences graduate student to travel to and from the Shetland Islands and provided shipping for some of the GPR equipment.

Location & Setting

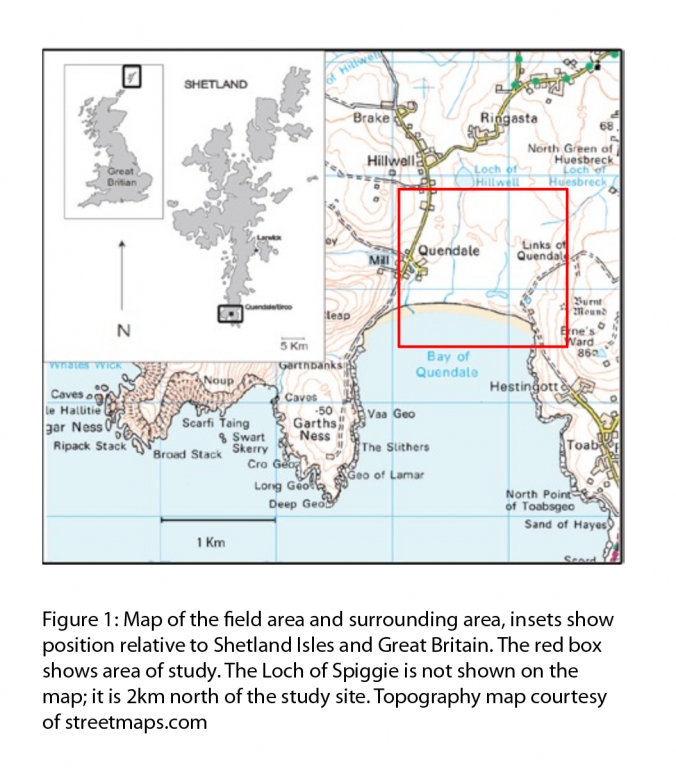

The Quendale Links of Dunrossness, Shetland is located 3.3 km northwest of Old Scatness, and occupy a broad valley that extends northward from Quendale Bay toward the town of Dunrossness. The Links are a 1.5 km long, a roughly triangular-shaped sand-dune covered area extending north from the bay on the central and eastern side of the valley (Figure 1). At the bay, the dune deposits are approximately 0.75 km in width. The dunes are covered with dune grasses. The surrounding hillsides are used for grazing sheep and cattle. Rabbits were introduced to the region in the past, and their burrows are common features in both the Links and the surrounding pastureland.

Summer weather in the Shetland isles is usually highly variable with short rain showers every hour and temperatures in the 40’s to 50’s, high winds are common during gales (http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/climate/uk/ns/print.html). This summer was unseasonably dry, sunny and warm with temperatures in the 60’s This is in contrast to last summer, when heavy rain and high winds often precluded field work.

2011 Research

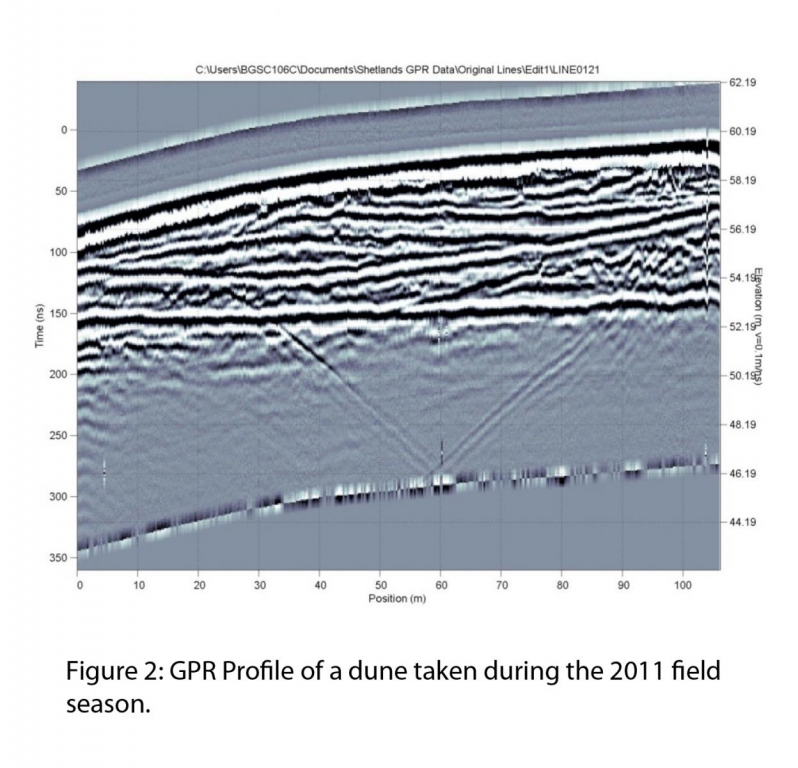

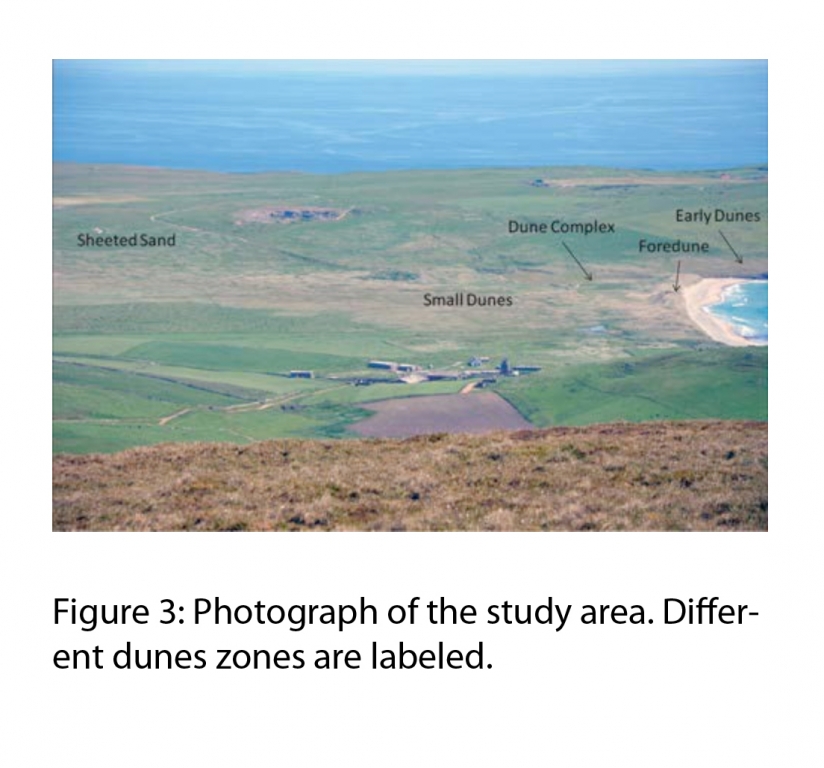

Reconnaissance ground penetrating radar (GPR) profiles were collected using a low frequency (100 MHz) device. Excellent stratigraphic records were collected in the coastal dunes, and provided the basis for the 2012 field season by providing information used in selecting the locations for OSL Dating (Figure 2). Last year’s field work and GPR surveys also revealed significant dune morphology differences throughout the study site. We hypothesize that these different dune types are caused by variations in depositional conditions, or combinations of conditions, and may also be related to more than one sand invasion event (Figure 3). At the archaeological sites, the 100 MHz GPR device, while excellent for examining dune stratigraphy, was unable to resolve buried walls at the archaeological sites due to lack of electrical contrast between the sandstone blocks used to construct the walls and the damp, windblown sand that now bury the walls.

May 22-June 5th 2012 Field Season

We arrived in the Shetland Isles on May 22nd, and began work the next day. All our equipment had already arrived and was waiting for us at our accommodations. We began the field season by locating the sites for acquisition of Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating samples. Our goal in attaining samples was to determine when the sand was deposited in each area and if it was the result of multiple events. Because the Quendale Links are a protected natural area, the Scottish National Heritage office was contacted to receive permission to excavate the faces. We chose sites on the sides of previous sand mine to minimize the disturbance, and were granted permission.

Once permission was granted by the Scottish National Heritage, we hired a backhoe and begin excavation of the faces selected for OSL dating. The operator of the machine did an excellent job of minimizing disturbance and replacing the material (Figure 4). We excavated three faces, two on the back side of the frontal dune and one in an area at the opposite side of the beach that was previously dated. The cleared faces were a meter wide and ~4 meters in height. One small trench was also dug in the bottom of the sand pit, and revealed approximately a meter and a half of sand overlying a cobble layer. Samples for OSL dating were collected at the base and top of each section to bracket the age of dune formation and stabilization. Sediment samples were also taken from every visible stratigraphic layer and at the location of OSL samples. When excavating the backside of the frontal dune; we found barbed wire 1.5m below the surface. As barbed wire has been in use for only 145 years, this suggests that this part of the beach has rapidly accreted and has been active recently. OSL samples were sent to the University of Sterling for dating. However, since OSL dating is expensive (£600 per sample), we will select a subset of the samples collected to by dated.

We also collected data using the GPR. Our first investigation site was a 15x32m rectangular area adjacent to the current Broo archeology excavation. This effort was designed to identify walls in an area that will be excavated next summer (Figure 5). Profiles were collected in a 1m grid, using the high frequency GPR (500 MHz). This equipment provided less depth penetration, but greater resolution than the previously used 100 MHz GPR. Field examination of the data showed many hard reflectors and hyperbolae indicative of scattered rocks. These findings suggest potential buried walls, though processing of the profiles is necessary before making definitive identifications.

We also used GPR in an effort to locate a buried inlet. Dr. Gerald Bigelow, the project director, noticed that older maps of the Quendale Links area showed an inlet connecting a lake, the Loch of Spiggie, to the ocean. We used both the 500 and 100 MHz GPR equipment to search for evidence of the inlet. This was accomplished by collecting long profiles along the beach and the road adjacent to the Loch of Spiggie. The 100 MHz antenna was used to get deeper penetration in the coastal sediments, while the 500MHz was used to identify near surface evidence of the inlet. Examination of the field data suggests the presence of a buried inlet. The identification of this feature will provide valuable verification of the old maps, and contribute to an understanding of the maritime history of the area.

We also used the GPR to expand our knowledge of dune stratigraphy. The 100 MHz antenna was used to examine a 15m*30m grid to investigate a small dune that had an unusual flat-top, and was close to one of the OSL sample sites.

Our second archeology prospection effort was at a site called “the Old House of Broo”. This site, approximately 270 m from the current Broo excavation, appears on both present day and older maps. Scattered rocks on the dune surface hint at buried walls. A 29m*30m grid was laid out over the site and profiles were collected one meter intervals. Confirmation of a buried building at this location could provide valuable information on the timing and process of sand movement and how people reacted to the crisis.

We also collected ten sediment samples from along the beach face, from one headland to the other. Samples were collected in the nearshore and backshore areas. These samples will be examined to characterize grain size and mineralogy to help assist in characterizing the system.

We also sampled the dunes we identified along the east side of Quendale Bay. These features are located seaward of the present day beach, and are composed of wind-blown sand with dunal morphology. We hypothesize that these early dunes were associated with earlier, more seaward located beaches formed at a lower sea level position. These dunes have the potential to be the oldest in the area due to their seaward presence. They have been subject to erosion from the ocean and have their cores exposed. This provides an excellent opportunity to gather samples for OSL dating. We sampled these dunes using hand-cleared, small faces to minimize disturbance. A face was cleared at the top of each dune and another at the bottom to obtain the oldest and youngest dates of dunes activity. Samples were also collected to be used to characterize the texture and mineralogy to the sediments.

Other activities under way at Broo during this field season include a joint University of Southern Maine and UNAFCO team surveying the dunes using LIDAR. This group also assisted in creating location maps of our GPR profiles and sample locations. A team from Bates College (Maine) and the University Of Bradford (UK) were conducting archaeological excavations at Broo. A researcher from the University Of Sterling (UK) was investigating soil formation at the archaeological site and collecting OSL samples in an effort to date the sand inundation of the Broo structure.

Conclusions

The grant by the Churchill Fund covered my travel expenses and shipping four crates of GPR equipment. In the past, we tried to hand-carry our equipment and encountered problems with airlines due to the size of the shipping boxes. Additionally, the boxes were roughly handled. Professional shipping meant the equipment avoided issues of crate size and out equipment was handled carefully. Everything was in place and in good condition when we arrived, and we could go right to work. A combination of good reconnaissance last year, hard work, great weather, and equipment in hand meant we were able to complete all our objectives this year and several side projects that will add depth to the study. We collected GPR profiles of dune stratigraphy, at two potential archeology sites and the position of a filled inlet. 12 OSL samples and a large number of sediment samples were also collected. We are excited about the information that this data holds to expand our understanding of the chronology and evolution of sand invasions in the Quendale Links. We are planning to present the data at the annual Geological Society of America conference in the fall.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our many thanks to Dan and Betty Churchill for allowing me the opportunity to go, to the Shetland Isles and to ship some of the GPR equipment to the site. We would also like to thank Dr. Gerald Bigelow, project director, for his interdisciplinary approach to this study. Thanks to Matt Bampton (USM) and Marianne Okal (UNAVCO) for their help with fieldwork and logistics. We also acknowledge funding by the National Science Foundation for funding Drs. Kelley’s participation in the project.

- Alice & Joe Kelley, Lee Sorrell

References

Bigelow, G.F., Ferrante, S.M., Hall, S.T., Kimball, L.M., Proctor, R.E., and Remington, S.L., 2005, Researching Catastrophic Environmental Changes on Northern Coastlines: A Geoarchaeological Case Study from the Shetland Islands: Arctic Anthropology, v. 42, no. 1, p. 88–102.

Burbidge, C.I., Batt, C.M., Barnett, S.M., and Dockrill, S.J., 2001, The Potential for Dating the Old Scatness Site, Shetland, By Optically Stimulated Luminescence: Archaeometry, v. 43, no. 4, p. 589–596, doi: 10.1111/1475-4754.00038.

Clarke, M.L., and Rendell, H.M., 2010, Atlantic storminess and historical sand drift in Western Europe: implications for future management of coastal dunes: Journal of Coastal Conservation, v. 15, no. 1, p. 227–236, doi: 10.1007/s11852-010-0099.

Dockrill, S.J., and Bond, J.M., 2009, Sustainability and resilience in prehistoric North Atlantic Britain: The importance of a mixed palaeoeconomic system.: Iron Age, v. 2, no. 1, p. 33–50.

Met Office, Northern Scotland: climate: http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/climate/uk/ns/print.html (July 2012)