COP 29 Blog

Baku, Azerbaijan, November 11th – 22nd, 2024.

Over the next two weeks, members of the University of Maine and Maine Law delegation will be following key negotiation streams including discussions linked to a new global goal for annual investments in climate policy, carbon trading mechanisms, adaptation for Indigenous communities, and operationalizing the loss and damage fund.

The delegates attend the negotiations to: 1) learn more about international climate governance; 2) conduct research related to the negotiations; and occasionally 3) to contribute to the process through speaking engagements based on expertise.

This year’s delegation includes two faculty and five graduate students, each with unique interests and perspectives on the process. They include:

- Nicholas Micinski – Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Affairs, University of Maine. FOCUS: climate migration and adaptation policy, particularly in the African Group of Nations.

- Anthony Moffa – Associate Professor of Environmental Law, University of Maine School of Law. FOCUS: carbon trading (voluntary and compliance markets), loss and damage (compensation for climate harms).

- Holly Fain – JD Candidate, Maine Law. FOCUS: Indigenous community participation, adaptation.

- Hailey Rizzo – JD Candidate, Maine Law. FOCUS: loss and damage, small island states, oceans.

- Jamie Dalgleish – JD Candidate, Maine Law. FOCUS: oceans, marine food production, loss and damage.

- Clea Harrelson – PhD Candidate, Anthropology. FOCUS: just transition, national adaptation plans.

- Sarah Ball – Graduate Student, School of Policy and International Affairs. FOCUS: gender, climate mobility, just transition.

Please follow along on our COP29 Blog below for first-hand and real-time insights into the climate negotiations. Keep an eye out for new posts each day!

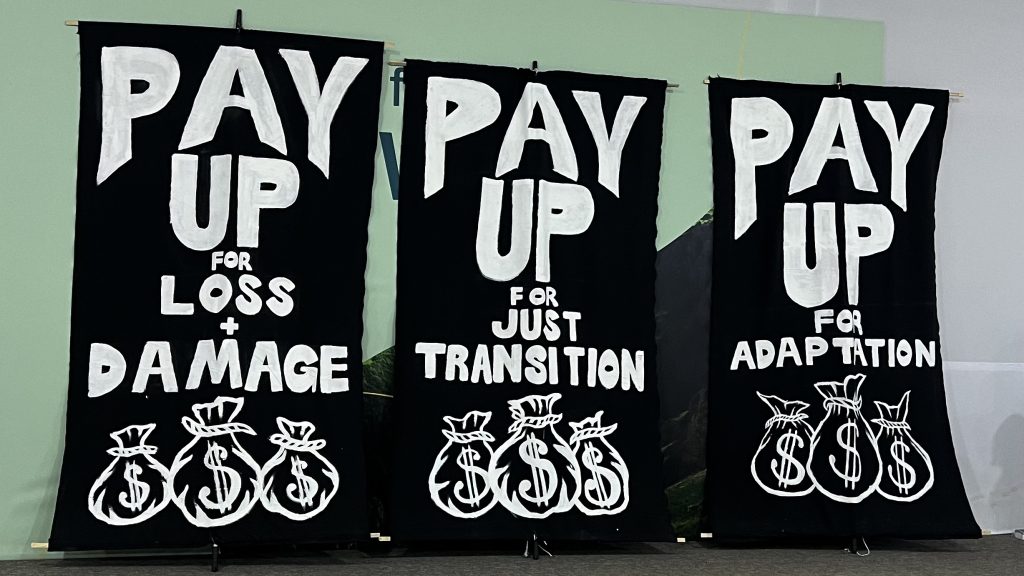

Follow the Money: What happens when climate negotiations are all about the money?

Prof. Nicholas Micinski, SPIA & Political Science

Nov 26, 2024

This year’s UN climate negotiations were billed as the Finance COP with the hope that states would agree to a new and more ambitious way of funding climate actions around the world. Previous years have had other emphases—like last year’s Loss & Damage COP (Dubai) or the 2022 Africa COP (Egypt)—but finance is always a part of the conversation.

This year’s delegates were tasked to agree to the New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance (NCQG) as an update to the Paris Agreement’s target of $100 billion per year. However, states failed to meet that goal ever since.

What happens to the COPs when the climate negotiations are all about the money? A few principles from political economy can help us understand what happened in Baku.

First, discussions were narrowly focused on the size of funding commitments—or the “quantum” as negotiators like to say. The G77 and China started this COP by demanding $1.3 trillion each year to address the needs of climate mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage. Donor countries baulked at this number, instead suggesting $250 billion per year by 2035. The hotly contested, final agreement set a goal of $300 billion per year by 2035 from developed countries. But the $300 billion goal is not adjusted for inflation–meaning the new commitment is only slightly better than the Paris goal.

But this focus on scale obscures harder questions about the winners and losers within that funding—and what is left out.

Mitigation versus Adaptation

In 2022, total public and private climate finance flows amounted to $1.171 trillion for mitigation efforts and $72 billion for adaptation. It is a political choice to prioritize mitigation over adaptation: Global North countries care more about mitigation (reducing emission), while the Global South often pushes for adaptation (deal with current impacts of climate change). In part, this is because countries in the Global South are more vulnerable and hurt more by the current and future impacts of climate disasters. But it is also because the Global South nations are worried that mitigation efforts could slow their economic growth or prevent development. Many poorer governments argue that they are willing to commit to mitigation goals as long as there are real commitments by rich countries to help fund their transition to clean energy.

The Baku Pact affirms that finance should strike a “balance between adaptation and mitigation” – but balance does not mean equal.

Public versus Private

Another big question was the type of funding: would the Baku Pact deliver concrete comments to public finance or general references to mobilizing private finance for climate action? Public finance includes government funding through public and multilateral institutions, while private finance comes from private banks or foreign direct investment and comes with different types of strings.

Again, the final agreement from Baku went general, stating that the $300 billion goal should be “from a wide variety of sources, public and private, bilateral and multilateral, including alternative sources.” This means that some countries will count private funding for their contributions to the goal.

Besides the public/private debate, poor countries also demanded that climate finance be channeled through the UN climate funds (Green Climate Fund, Adaptation Fund, or Loss and Damage Fund) because multilateral funds are supervised by the UN, transparent, and democratically accountable. In contrast, rich donor countries use bilateral finance to favor their allies, benefiting some regions over others, and without the same requirements for transparent reporting. The Baku text decides for “at least triple annual outflows from those Funds from 2022 levels by 2030 at the latest with a view to significantly scaling up the share of finance delivered through them.” This is strong language and promises to grow the UN funds if states follow through.

Grants versus Loans

Countries also are worried about the balance of grants versus loans. The Global South pushed for grants because they would not be required to pay them back, while loans—even concessional loans—would balloon national debt for poor countries already struggling with high debt burdens. These countries are also concerned about access to debt financing because many of the most heavily indebted countries do not qualify for private loans and sometimes struggle with concessional loans from multilateral development banks (MDBs). However, many analysts agree that grants can never meet the global scale of need for climate finance, and so some mixture of loans and public-private partnerships will be necessary.

The Baku Pact nods toward this debate by urging MDBs to “eliminate conditionalities for access” and invites financial institutions to use a range of tools including “non-debt-inducing instruments.” One of the weakest parts of the text merely suggests “considering shifting their risk appetites” and “considering scaling up highly concessional finance.”

This is why developing countries were outraged by the Baku Pact: instead of concrete commits for public grant-based funding, the text waves at every kind of financial tool with a relatively modest “quantum.”

Who Pays?

Finally, the Baku Pact does not answer who pays for climate action. One of the institutional legacies within the UN process is that the Kyoto Protocol committed developed countries (Annex I) countries to take actions to reduce emissions, including providing funding for less developed countries. The countries defined as developed (and thus expected to donate) still reflect 1990 when they were first established, despite major changes in the global economy since. For example, China’s GDP per capita was $905 (adjusted to constant US dollars in 2010) in 1990 but in 2023 was $12,174. However, China is still defined within the UNFCCC as a developing country and not expected to be a donor to climate finance.

At COP29, the EU and US pushed hard to redefine which countries should be donors but that did not make it into the Baku Pact. Instead, the text: “encourages developing country Parties to make contributions, including through South–South cooperation, on a voluntary basis.” This acknowledges that China and other non-Western countries are increasingly becoming donor countries while reaffirming that their contributions are voluntary.

This year’s Finance COP went over by a full day with negotiations late into the night—prompting protests by civil society and angry speeches by the least developed countries. The Baku Pact sets out an overall target of $300 billion per year for climate finance—tripling the previous goal—but the agreement doesn’t resolve some of the most important questions about who pays, for what, where, and how.

The legacy of Baku might be that the scale of climate finance increases but it will not resolve these thornier questions which are ultimately about climate justice and global inequality.

The Intersection of the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change with Other International Legal Instruments Relating to our Oceans

Jamie Dalgleish, Maine Law Class of 2025

Energy & Environmental Law Society Co-Chair

Nov. 27, 2024

I still have to pinch myself because I feel so lucky to have attended COP29. I’ve devoted myself and my work to the environment since I was a teenager; and having studied international environmental policy as an undergraduate, actually being physically present at a UNFCCC event to see how it works on the ground was so incredibly professionally rewarding.

I earned my B.A. in Environmental Studies with a minor in Environmental Science from Mount Allison University, within the U.N.-designated Fundy Biosphere Reserve. During that time, I studied abroad with the Sea Education Association, conducting physical oceanographic research on a transatlantic crossing by sail to determine whether climate change affected particular water masses in the Tropical North Atlantic Ocean. That was my introduction to the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Now studying at Maine Law, as a candidate for a Juris Doctor I am also a candidate for a Certificate in Environmental & Oceans Law. As such, I am studying abroad on exchange this semester at the Arctic University of Norway, where I have learned General Law of the Sea, through the Norwegian Center for the Law of the Sea, and Indigenous Peoples’ Rights while remotely continuing to serve on the Ocean and Coastal Law Journal.

While COP29 was billed as the ‘Finance COP’ for its focus on Loss and Damage mechanisms and for determining the NCQG, I focused on intersections at COP with oceans-related legal instruments. The global ocean is the Earth’s air conditioner, and marine flora can store up to four times as much carbon as trees can. Coming from Maine, my specific focus was on aquaculture–as that industry is booming in the Pine Tree State at the moment–both as a means for carbon storage and as a food source.

Going into COP29, I knew that with my general and my specific foci that I would not observe many formal negotiations given this COP’s finance focus. With that in mind, I made the Ocean Pavilion my unofficial base. As luck would have it, the Ocean Pavilion was run by two institutions with which I already had familiarity: Scripps, and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (WHOI).

After being badged into the “blue zone” of COP29, I headed to the Ocean Pavilion to attend my first panel: Deep-Ocean Biodiversity. This panel was a fantastic lineup of speakers, and I learned a lot given the noise and time constraints. It prompted me to think about the ecosystem services of biodiversity in the deep ocean, namely that biodiversity acts as a carbon pump for carbon cycle services. This can value $300MM annually . I had not previously considered biogeochemical cycling in this way! This panel also tied in the recently-drafted BBNJ Treaty, or Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction, which is also a U.N. document. It connects the Law of the Sea to more environmental protection and tackles the legally complicated nature of transboundary environmental protection.

I got to ask a question of the panel. I learned while on exchange that Norway recently decided to open its seafloor to mining, and has already extended contracts for mining, despite the research and development not yet being capable or logistically possible. In keeping my finger on the pulse, I have also heard the idea of a global moratorium on deep-seabed mining bandied about. Given the lesser, albeit still present, focus on the “Just Transition” away from fossil fuels to electrification and its need for more mining of rare earth minerals and elements to produce batteries and photovoltaics, I am curious about how to square that with preserving deep-sea biodiversity. In short, development and conservation are often pitted against each other, and I wrestle with how to resolve that. No one had a great answer, but I did learn about a new type of battery that could render deep-seabed mining moot: iron phosphate batteries, made mostly in China, don’t use nickel, cobalt, or other rare-earth elements and minerals that lithium-ion batteries use. Of course, that leaves iron nodules, which form over millions of years; the answer to that quandary was that mining those would irreversibly harm deep-sea biodiversity.

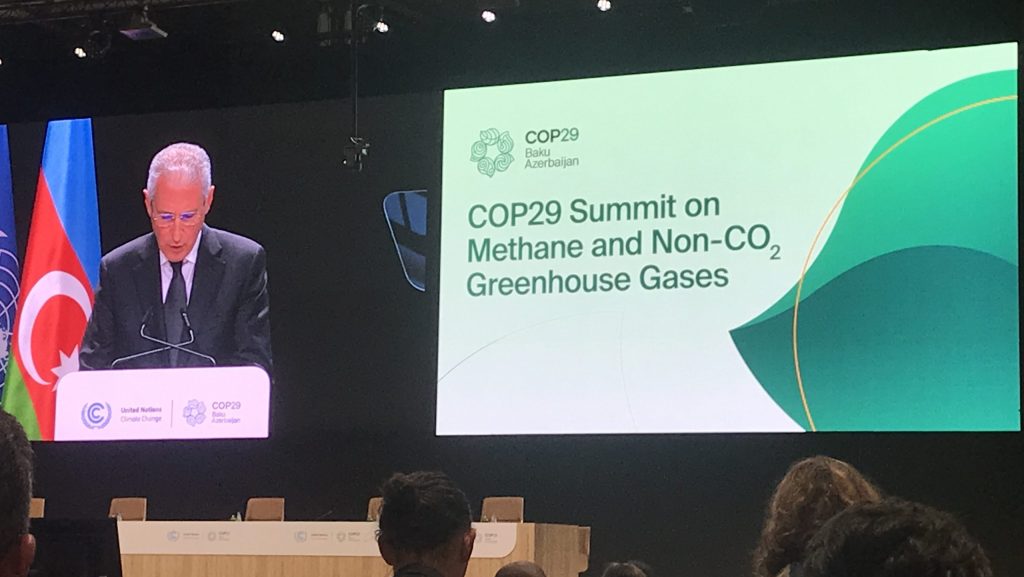

That afternoon I attended a ticketed plenary session: COP29 Summit on Methane and Non-CO2 Greenhouse Gases. John Podesta, the U.S. Senior Advisor to the President for Clean Energy Innovation and Implementation, spoke on a panel. I gleaned good context from his input. He described the last four years as a watershed for commitments and action to reduce Non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions. Other panelists included the Special Envoy from the Peoples’ Republic of China, the European Council President, and the U.K. Energy Minister, Ed Millibund, who shared that Britain would announce its NDC that day. He also put methane into context, saying that “if carbon dioxide [reduction] is a marathon, then methane [reduction] is a sprint” and that “we need to go further and faster.”

On Thursday afternoon I returned to the Ocean Pavilion to attend two panels: one on climate change and multidimensional impacts on small-scale fisheries, and the other on marine carbon dioxide removal (mCDR).

mCDR Panel: I got to hear from Jill Storey of the World Ocean Council, and Paul Morris of Exploring Ocean Iron Solutions, as well as a representative of NOAA. I was keen on what Paul had to say about recent developments in iron fertilization, since iron is the limiting nutrient in the open ocean for carbon dioxide fixation by tiny plankton. I was disappointed to hear Jill Storey quote McKinsey, but it was interesting to learn that McKinsey pegs CDR as a trillion-dollar market. I also got some class review when the panelists underscored the recent International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) decision noting CO2 as a pollutant; however, in the same statement ITLOS went on to say that mCDR must be in compliance with the London Protocol, see 1996 Protocol to the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter, 1972, which is to say that because there must be no ocean dumping, iron fertilization is, legally, a difficult task to achieve. I was excited to learn that just that day NOAA released an mCDR plan! NOAA, White House, others release strategy for Marine Carbon Dioxide Removal Research, Press Release, NOAA (Nov. 12, 2024). It will be interesting to see how this plays out given that the U.S. ratified the London Convention and the London Protocol.

On my last day, the Friday of Week 1, we were lucky enough to be given the opportunity to head to the Azerbaijan Supreme Court for a roundtable discussion on nature, water, and resources amongst justices and judges of other countries’ courts. We were the only students in the room, and it was a surreal experience not just because of that, but also because we got to witness firsthand other countries’ top justices discussing implementing ecocide and environmental damages in their opinions as a matter of course, when in the U.S. that is virtually nonexistent or a steep uphill battle. It was eye-opening, to say the least. It was rewarding to hear about the ICCPR in real life, having spent the semester learning about it in my Indigenous Peoples’ Rights course; and to hear justices also discussing the recent ITLOS decision noting CO2 as a pollutant, having learnt that in my Law of the Sea course!

And of course, as law students it’s always a wonderfully nerdy experience to see another high court! This was my second Supreme Court visit of the year, having toured the U.S. Supreme Court this summer before I started my Office of Legislative Affairs internship at the U.S. Department of Justice. The two Courthouses are quite different!

Friday was also the day the U.S. Congressional Delegation arrived. Given my previous political and government experience at the state and federal levels, I was keen to learn about this Delegation’s interaction with an international climate conference. I followed Senators Markey and Whitehouse around the pavilions, including following Sen. Markey to the Parliamentary Pavilion. There, he was on a small panel with other subnational elected officials to speak about how to address climate change at that level when the international forum is not the most effective (at least at this COP).

As expected, Senator Markey had some great quotes:

“Politics is a stimulus response institution, and there’s nothing more stimulating than having your constituents yelling at you because you’re killing their industry.”

“You can’t preach temperance from a bar stool.”

“Adam Smith is spinning in his grave so fast it would qualify for a tax credit under the Biden Administration’s Inflation Reduction Act.”

Senator Whitehouse made a good point that carbon removal is essential because “there are no paths to carbon neutrality without carbon removal.”

A Grassroots Experience at COP29- A Focus on Earth’s Parties, Indigenous Peoples and Communities

Interview with Indigenous Peoples’ Caucus Member, Krista Clement, & How I Ended Week 1

Holly Fain, Maine Law

Nov. 26, 2024

My Last Grassroots Action of the Week

At 9:00 AM, while Professor Moffa attended the RINGO morning briefing, and Hailey Rizzo and Jamie Dalgleish attended the Azerbaijani Supreme Court’s panel of justices presenting judicial perspectives on Climate Law, I attended the International Indigenous Peoples’ Forum on Climate Change briefing. Today’s agenda focused on the Thematic Group updates of Article 6 and included the following: Thematic Group Update, Article 6, Finances, Youth activist group updates, Local Communities and Indigenous People’s Platform (LCIPP), Mitigation and Just Transition, Adaptation, Loss and Damage, Closing Plenary Session SBSTA and SBI reminders, and an opportunity for any other attendees to share their updates and concerns.

I knew this was going to be my last, most significant chance, to get summaries from anything I missed the previous evening, while also setting up my evolving plan for this last day of my COP29 followings.

As soon as the briefing concluded, I dashed for someone I had been wanting to speak with nearly all week, a member of the Indigenous Peoples’ Caucus at COP. She caught my ears all week in some of the spaces I was following, and this was my opportunity to say hello and interview her.

Some relevant background to the Indigenous Peoples’ Caucus

At the COP21 (Conference of the Parties 21) in Paris, the 195 participating parties agreed to the first ever universally binding accord on climate change, the Paris Agreement. In preparation for Paris, the Norwegian government donated funding to enable greater Indigenous participation in the process. Regional consultations of Indigenous Peoples took place in all seven regions of the world and dozens of Indigenous representatives from around the world came to Paris, including numerous representatives from United States tribes. This participation was crucial in lobbying for language concerning Indigenous issues in the Agreement itself and the Decision adopting it.

The Indigenous caucus had several issues which it pushed for inclusion in the Agreement. One of the most important was to get a provision in the operative section of the Agreement recognizing that climate change policies and procedures had to respect, protect, promote, and fulfill the rights of Indigenous Peoples within a broad human rights framework. The effort resulted in a provision which states:

Acknowledging that climate change is a common concern of humankind, Parties should, when taking action to address climate change, respect, promote and consider their respective obligations on human rights, the right to health, the rights of Indigenous Peoples, local communities, migrants, children, persons with disabilities and people in vulnerable situations and the rights to development, as well as gender equality, empowerment of women and intergenerational equity.

A second issue of importance to the Indigenous caucus was the recognition of the importance of Indigenous Peoples’ knowledge in relation to climate change. To that end, the Paris Decision established a Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform to provide an opening for traditional knowledge to influence climate policy at local, regional, and international levels.

The Interview

Furthermore, I had the privilege of speaking with a very special member of the Indigenous Peoples Caucus, Krista Clement. She is the Director for Environment & Climate Change Policy, International and Intergovernmental Advocacy for Indigenous Climate Leadership for the Métis Nation of Ontario. Clement brings extensive experience working to protect and promote the rights of statelessness among Indigenous communities, women, and children. Her work has led her to India, Burma, and Thailand. She holds an MA in Sustainable International Development, and is a member of the Métis Nation of Ontario.

Holly– Thank you for allowing me to snag some of your time, explain the grassroots mission I’ve been on this past week as a Native law student, and thank you for allowing me to ask you a few questions!

Clement– Of course, what would you like me to talk about today, Holly? [She asks with inflection and with a big grin on her face]

Holly– I would love for you to tell me about what you started doing with COP, where you are today with COP, and what you feel like your grassroots action of today is?

Clement– Ooh, my grassroots action of the day, good question! So where did I start? So I’m Métis, from northwest Ontario from a community called the Brady River. And I’ve kind of gone on a journey throughout my career, worked in Southeast Asia for quite some time, in Indonesia and West Papua, helping Indigenous communities out there develop climate financing mechanisms that are Indigenous-led and with direct access. So things like endowment funds, and revenue from Indigenous-led protected areas that were created for ecotourism purposes. So that’s kind of how I got to the climate finance space, after my work there, I decided to go home and help my own community because I had some great experience and I didn’t really want to go back to my community without experience because there’s a lot of really knowledgeable people there who I needed to provide some benefit…. So, I’ve gone back home and now in this role, where I’m supporting the nation, more broadly to think about really how we’re going to be able to advance our climate change priorities, protect our culture, protect our land, to protect our ways of life.

Holly– Oh, I bet the pressure has been intense, and of course you felt like you needed even more expertise than ever before…

Clement– In terms of what I’m doing at COP, I’m here just supporting the Indigenous Caucus and more broadly since it’s my first time working with this Caucus at COP, I was at Paris long time ago, but I was there in a different capacity, when it wasn’t really a safe space to be an Indigenous Person, which is kind of cool. So it’s really nice to see the community that’s developed here as a result of that, and you know, how I’ve learned how this caucus functions is really grassroots…It’s like, from the ground up– you get in there, you see what’s going on, you donate your time, you donate your skills, and make things happen, and it’s all just very organic. And you know, we all organize on our WhatsApp groups.

We’re super in touch with what’s happening, day to day, we follow it, we’ve got point people. We’re just taking action as it happens! And a lot of what we’re doing right now is we’re focusing on the NCQG. And making sure that the language that’s included in that document is representative of our communities and doesn’t hurt our communities.

Holly– And where are you telling me to go today, my last day at COP?

Clement– And where I’m telling you to go today is to make sure that language is in there.

Holly– Thank you so much, Krista, it looks like you have to run. I hope to see you again sometime. You’ve really lit me up today!

Clement– Do you have the Signal App? I’ll add you to the IP A6+LD Working Group.

[And with that, Clement was off to the Negotiation Rooms races]

Unpacking a Brief Deep-Dive

Clement’s reference to what is “hurting our communities” is referring to the looming role of Carbon Markets; they are a huge issue right now. The Developed World right now is firmly pushing for a significant component of Climate Finance to be allocated to the private sector. Through carbon markets, which can be harshly exploitative of Indigenous communities and cause a lot of problems for these populations. Overall, the item of language is critical here and needs to be appropriate, included, and it is crucial that the Caucus gives their feedback where they can.

I took a big gulp of my coffee (was that my 2nd or 3rd coffee today?) and I thought deeply upon what I just heard. I quickly started synthesizing this past week’s exposure to the UNFCCC textual framework of “The Position of Indigenous Peoples on CMA” and thought, dang, I really need to see the current working group’s document of language recommendations, basically, I needed in on this action today. Talk about a last-minute “souvenir” search. But Clement had already darted off and I knew I had to find another collaborative person, and ask if they could lead me to the document or link, or just let me shadow them. I walked back into the meeting room, where IIPFCC attendees were still buzzing and chatting, and found a welcoming face. Who was I kidding? I was in the Indigenous Peoples network, we all had welcoming faces, it’s always so warm in this circle, regardless of how far you’ve traveled. Kindness and sharing is a culture, y’all. Never forget that.

Making eye contact with another hard working lady sporting a smile on her face is how I made the connection to be shared on the living document for language suggestions draft of “The Position of Indigenous Peoples on CMA 6 Agenda item 11(a), NCQG” as of the 16th November 2024. This share was thanks to a new friend, Jayce Chiblow, who is the Director of Education & Programming at Indigenous Climate Action in Canada.

I followed the working group’s living document’s language suggestions all afternoon, as I attended COP’s Informal Consultations. It was kind of like a read-along for me. There is a strong emphasis on suggestions that relate to language such as [upholding the rights of Indigenous Peoples to self-determination and the obligation of states to obtain the Free, Prior and Informed Consent of Indigenous Peoples prior to the approval of and as iterative process in any project]

Here’s what things looked like at the time:

As suspected, language matters, text matters, and thus technical negotiations matter in the further protection of Indigenous Peoples and frontline communities. It always has, and that’s the power of words when it comes to the physical word of climate action. The impression here is, we have to make sure that language is in there!

Later that Day

Ghazali shared that Indigenous Knowledge was being discussed in regards to Article 6.4 guidance next to science. The deadline for input was approaching soon and the groups would need to lobby parties immediately.

Indigenous Peoples proposed following edits:

Section I

1. Requests the Supervisory Body and the Secretariat to ensure that adequate technical and scientific expertise, [and relevant Indigenous knowledge] is available to support their work on methodologies, removals, and related operational elements…

2. Requests the Supervisory Body to establish, or periodically convene, expert panels comprised of external experts with relevant scientific expertise, [Indigenous Peoples with relevant Indigenous Knowledge] ensuring that such panels provide technical review and input on recommendations before it adopts them.

As shared by Ghazali Ohorella, at the IIPPCC Daily Programme this morning, in COP Negotiations, a “consensus in climate talks isn’t what you think” and that as of the negotiations in Article 6, “nobody is going to be happy; everyone will be equally frustrated.” That was striking to hear at this dense, stratified framework of negotiation tracks and diverging party interests.

He shared that after 6 years in Article 6 negotiations, he’s learned that “countries might nod in agreement” and make deals, but real progress is different. Ghazali says if you “follow the money trail,” you will see that “Article 6.2 (bilateral trades) gets all the attention, while Article 6.8 (non-market solutions) gathers dust because profits are greater than cooperation.”

What do you know, profits are still the driving force, even as the Earth’s voice is getting hoarse from crying for help, and Earth’s parties, the Indigenous, have to sideline COP negotiations in efforts to prevent further mess. I was sharing with my Maine Law Delegation friends at dinner the other night that I have been swimming in a sad sea at COP. The reality of being a grassroots observer and participant here is devastating since all of the COP29 negotiation tracks impact Indigenous lives. Earth’s parties do not get to fly home to further comfort, worldly distractions, or a better life, they have to brace for another year of hardship. Resilience is not a trend or catchphrase for them, it is survival.

I must say, as my grassroots journey and participation at COP29 is coming to a close, this has been a life-changing experience for me. This was my first– probably only delegation– to COP. It has been intense in almost all aspects: learning to navigate the negotiation tracks, following the content that I found most meaningful and braided into my mission based on each space I entered, then deciphering all the information I was being flooded by in order to build a better understanding of the efficiency and impact of COP29. Talk about adaptation, I found myself going with the flow at times, following new people who I trusted enough to take me somewhere meaningful and teachable, then changing routes as needed in order to jump to an area where a panel, conference, exhibit, or discussion was just too tempting to risk missing.

Some root strengths and skills that carried me all week were my fortified social gears, my love for meeting new people, actively listening to voices who ring out for justice, activism, and obvious rugged non-conformity. I remained open-minded, flexible, and despite the devastating tone of most of the content I was tuned into, I kept chugging along the pathways of the Global Goal on Adaptation, Indigenous Peoples, and Indigenous Peoples’ traditional knowledge and the profound understanding of ecosystems, environmental protection and stewardship, and grassroots resource sustainability.

Roger, over and out- Abisha’i,

Your Grassroots Girl,

Holly Fain.

A Grassroots Experience at COP29 – A Focus on Earth’s Parties, Indigenous Peoples and Communities

Some Powerful Days of Indigenous Stories, Climate Impact, and Resilience

Holly Fain, Maine Law

Nov. 26, 2024

The Past Few Days’ Impressions are Those of Harm and Hope

I have been spending all of my spare time at COP (when not in other briefings, press conferences, and side exhibits), at the International Indigenous Peoples Platform on Climate Change pavilion (IIPPCC), where there is a small lounge of couches, coffee tables of Indigenous groups’ and NGO brochures (ranging from climate reports, projects, and policy notes), and a panelist stage and audience listening area. I have attended, interacted, and engaged with at least 16 presentations already (lots of free coffee and my Maine Law notebook have kept me going). It is a more intimate pavilion, not very high-tech or upscale like other COP29 countries or industry pavilions– which I’ve been told cost $1 million or more depending on the space– but it is where I have been learning the most thus far. Grassroots activist culture is characterized by a bottom-up approach and can focus on causes like human rights, social justice, and climate change. Grassroots movements often use modalites like presentations, gatherings, informal meetings, performances, simplified language, and inclusive approaches. These engaging approaches make a greater impact on learning, inspiring change, and in my opinion, exciting people.

At the IIPPCC, many Indigenous representatives shared their perspectives and frontline experiences of what their lives once were, and what they are like now, and let me tell you, it is devastating. From food insecurity (including the loss of nomadic farmer livestock), rising sea levels, home destruction, farmland threats, forest and tree destruction, contaminated water, air pollution, and diseases, daily life is about being resilient and protecting your loved ones. These Indigenous People discussed how their communities are tackling climate threats, green colonialism, and the tricky dynamics of Carbon Market cowboys’ dealings. Hearing their voices from the intimate pavilion where us observers could sit, tune in with the translator headsets, and visit with the attendees was one of the most special experiences I could have at COP29.

Despite the evolving hardships of climate impacts, these frontline communities serve their villages, children, and families immediate needs every day. Their traditional practices are how they avert further climate impacts, not just adapt to it. The Indigenous groups attending and presenting at the IIPPCC pavilion, side exhibits, and press conferences for the past few days took turns describing how climate change is impacting their communities and many explained how their communities are helping to combat climate change and prevent further loss. Water crises have to be resolved by desalination plants in order to balance drinking water reserves. Controlled fires have to be managed for soil needs (as many of us Native Americans understand).

When rivers that are historically used for village commuting run dry, new paths have to be made. Trees MUST be planted constantly. Floods are destroying homes and resulting in many deaths, so migration is non negotiable.

Indigenous community speaker narratives came from frontlines and villages of Russia, Chile, Sydney, Ecuador, the Wind River Reservation in the United States, Belem, Brazil, Khumbu Pasang Lhamu Municipality District, Nepal, Chad, Brazil, Papua New Guinea, Chad, and Malaysia.

Lands are Not Just Land, They Hold Life, Identity, and Knowledge Systems

In Indigenous pastoralist communities, several people of the Mayo-Kebbi East community in Chad described how pastoralists combat the effects of climate change with nomadic strategies such as migrating to different farmlands seasonally which allows cow manure to rejuvenate soil so that it can be fertilized and further replenish the ecosystem. In the Pacific NGO Association, members are working diligently to facilitate forest management, lead education programs, town halls, workshops for women and children, and building seawalls from hay to combat rising tides. When nature-based medicine disappears due to portions of biodiversity disappearing, new medicine has to be created, and it might not be as reliable. Plants are medicine, and the loss of native plants is detrimental to Indigenous healthcare.

At the SDG Pavilion, I listened to Indigenous professor, Dr. Myrtle Ballard, who thoroughly referenced Indigenous Science, Indigenous Knowledge, Local Knowledge, and Traditional Knowledge systems of Indigenous Peoples as everything from childcare practices to how traditional housing is built. She said, “Indigenous Science is about the knowledge of the environment and knowledge of the ecosystem that Indigenous Peoples have… and it is the knowledge of survival since time immemorial and includes knowledge of plants, the weather, animal behavior and patterns, birds and water.”

Indigenous science is about the knowledge of the environment and knowledge of the ecosystem. It is holistic and done in real time, current, evolving, distinct, time-tested, and methodological knowledge systems that can enhance and complement western science. There is an innate relational values that Indigenous People have that distinguish Indigenous science from western science, it also includes a philosophical process by which Indigenous Peoples build their experiential knowledge of the natural laws, natural environment and land. For instance, when tribes create

For Indigenous women, especially the ones who are mothers, managing farms and animals, and responsible for children getting an education despite climate disruptions, every day is a balance of immediate needs and sustainable techniques. If their husbands have been killed in wars, which many are, then all these hardships become a constant. And do not forget, that when people get displaced, their language and culture is spread even thinner, and it is usually women and mothers who have to ensure their communities stay fluent in their native language.

One of my Favorite Events

At the Guardians of Mother Earth Presentation, laying the foundations for the relevance of celebrating this day within the framework of COP29. It was a curated space for spiritual harmonization, with sisters from each region of the world to present worldviews of their people through narratives, songs, poetry, dance, legends related to caring for Mother Earth. This thematic panel was led by moderator, Tarcila Rivera, who reminded me so much of my adorable mother. It featured lessons about the resilience of Indigenous women to the impacts of climate change and how the exchange of knowledge and experiences empowers us further. Discussions were centered on how climate change affects women and what actions they are taking to address the impacts using their own knowledge.

It was a beautiful panel, also heartwrenching, and one of my favorite parts was listening to the representative from the National Inuit Council of Canada speak of the factors that play into Inuit-impaced climate change, especially rising temperatures disrupting ecosystems and altering wildlife patterns which affect hunting and fishing. When the fishing industry is what feeds most families and fuels their economy, melting ice and rising sea levels in the Arctic regions, continues to threaten their survival, developed countries forget this many times, thinking of hunting and fishing as sport.

Youth on the Frontline: Pushing Discourse and Supplying Smiles

Sarah Ball, UMaine School of Policy and International Affairs graduate student

November 20, 2024

For what promised to be a contentious COP – from concerns for the human rights records in the host country to fossil fuel connections to involvement to promises of the “Finance COP” – week two started sleepily. Subsidiary bodies closed, with many hot topics being delayed, rejected, or moved to the COP Presidency as ministerial work. Negotiations on global stocktake are still going back and forth on items such as the inclusion of gender and losses and damages. In a press conference on Tuesday evening with CANSA, vulnerable states reiterated the urgency and need for $1.3 trillion USD, a finance goal that is not on track to be achieved at this COP. Negotiations are ongoing with expected new drafts texts Wednesday evening. The high concentration of local police outside the venue created an atmosphere of compliance and streets were largely empty of life. Yet, as bleak as the negotiations felt, COP29 was very alive in its second week. As youth movements, where galvanizing action typically have been restricted to within designated areas, new arenas for youth involvement has been essential in keeping morale during a slow moving COP.

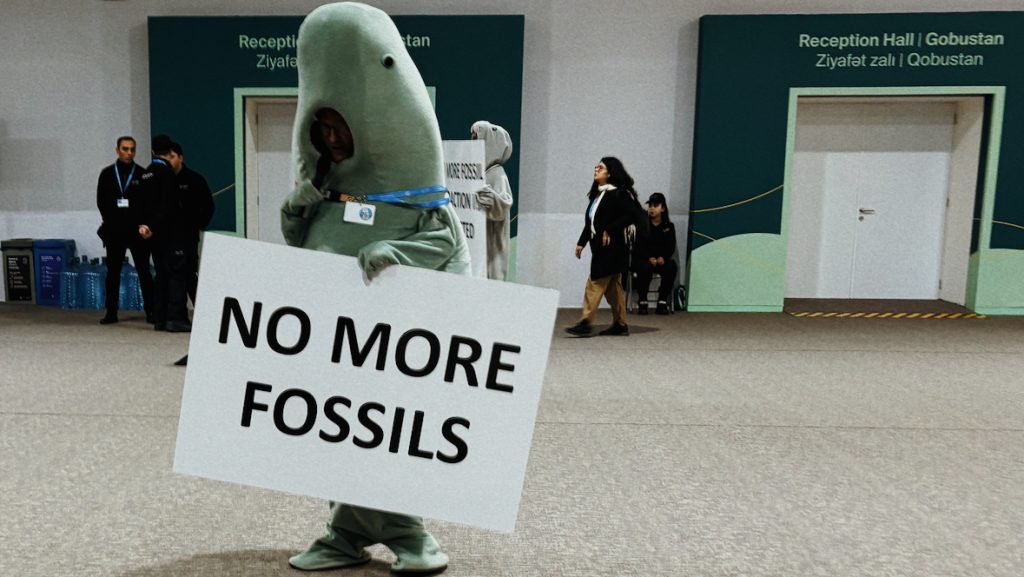

Within the UN designated spaces, some action is always happening. A dancing manatee was a protest against fossil fuels extraction in protected areas. Feminists called for a fulfillment of the Lima Work Programme for representation within negotiations and inclusion of gender within negotiations. Others read the names of the children killed in Gaza by Israeli strikes. Numerous organizations called for the end of fossil fuels and criticized carbon markets. These events were exclusively inside the venue, behind stanchions on the carpeted plywood floors, with clear time restrictions. There were the typical youth-led side events, exhibits, and pavilions. This is what I expected of youth presence at COP29. Addressing current topics and pushing for action on these measures outside and inside of the events listed on the program.

There was a second side to youth involvement. Throughout the COP, Azerbaijani volunteers were every couple yards inside and outside the venue to answer questions and provide directions. They were in every room, running microphones and headsets. Our delegation mused on the cost of outfitting these volunteers in matching polos and jackets. The vast majority of these volunteers were young youths, many in high school or at least under 20. As Baku provided a two week break to schools – a potentially controversial aspect of the management of this COP – high schoolers were given the opportunity to volunteer during their break. And many took the opportunity. This was a different side of youth involvement that I expected. These volunteers were incredibly helpful and willing to help but very open about being teenagers. As they provided transport directions, they danced with light sticks. The openness of the volunteers to be teenagers and engage with fellow volunteers and attendees as teenagers provided a needed osmosis of energy.

Climate change requires us to think about the future and how we will continue to engage with climate policy. Youth movements have pushed the discourse and been key stakeholders in the policy outcomes of the COPs. Baku offered a unique mechanism for youth involvement. It was refreshing to have youth involvement – and true young people – as the cornerstone of COP. Youth involvement in the process is expanding, despite the restrictions for traditional activism which is increasingly restricted and bureaucratized. I am not optimistic that this will shift the overall trend of youth involvement despite being integral to the ease of COP29 and uplifting daily affair.

Dealing with Conflict

Clea Harrelson, UMaine Anthropology PhD student

Nov. 20, 2024

The 29th Conference of the Parties of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (COP 29), brings together 198 Parties (197 countries plus the European Union) to discuss climate change. It’s the central mechanism that gave life to prominent climate agreements such as the one that came out of Paris in 2015, a platform for regularly meeting to discuss and coordinate climate actions, in addition to flashy, if consolatory, monetary pledges, and an arena in which countries grapple with global relationships. Unsurprisingly, it’s a space full of disagreement and compromise.

As leaders and experts from each country sit in negotiation rooms around sleek white tables arranged in a square, microphones click on and off with a pop as people respond to the facilitators or comments from other countries. Most interaction is coated in formal politeness (e.g. “Thank you to my colleagues for all the hours of work we have put into this text…) only to be followed by statements such as, “We’re not going to entertain any re-negotiation of this paragraph, so I suggest we move on…” Confrontation is not unusual but also not the only strategy to resolve conflict. Countries and facilitators use a suite of strategies to move negotiations forward.

While likely not an exhaustive list, I witnessed seven main ways people deal with being stuck on an issue or agenda item. First, people representing their countries are often master editors, scribbling notes on the fly, rearranging, combining, or re-writing items within minutes of disagreement being raised. Putting forward alternative text as a solution for disagreement is the most straightforward path towards consensus. In situations where the disagreements are too divergent to be smoothed over in open, miked conversation, delegations often take advantage of “huddles” before, after, and occasionally during a negotiation, gathering together around a few central speakers like a sports team listening deciding on the next play to quickly hear others’ opinions.

If huddles are too brief and more explaining or convincing is required to sway another group’s perspective, the facilitators or a country may suggest an “informal informal,” a mildly confusing and repetitive way to say that negotiators need more time to mingle and discuss in a setting even more informal than the one made possible through open negotiation meetings. In some instances where a group is struggling to make progress across parties, I’ve also witnessed facilitators offering, and even strongly suggesting, a way forward. As arbiters of procedure and with access to UNFCCC legal experts, facilitators may outwardly strive to be neutral but in fact represent key points of influence for any given negotiation.

Once an issue is deemed to be beyond the help of a facilitator or the parties themselves, the Presidency of any given COP may suggest or facilitate conversations among high-level officials from each country. This shifts responsibility for a country’s position on an issue up the governmental chain to people who are more likely to have the authority to compromise or suggest new alternatives than those actually at the table. Presidencies may also hold consultations themselves to speed progress or pressure countries to action. And finally, when all else fails, conflict is resolved only temporarily by pushing decisions to future meetings of other subsidiary bodies of the UNFCCC. While this last option may read as failure, groups working at COP may still be able to forward substantial amounts of draft text to these other meetings, meaning the work does not start over completely. None of these options are perfect and many happen simultaneously to one another, with negotiators smoothly switching between strategies.

The ability to navigate these processes is also clearly not equal among delegations. In one meeting I attended, the United States came with three support staff all working in a shared document while a negotiator from another country sat alone. I suspect this inequity in resources impacts some countries’ willingness to speak at all, as there are often only 5-8 people out of 50+ around any given table who are vocal in open meetings.

COP is fraught with all the same realities of the rest of our world, and thus disagreement in these spaces is inevitable given how differently people experience climate change and the vast differences among hopes for the future. Understanding what levers are possible to resolve immediate conflicts at COP, as a negotiator or an observer, is one way to try to survive the swirl of climate change discussions, even if it seems the swirl of COP29 may carry us away without real resolution in the end.

A Grassroots Experience at COP29 – A Focus on Earth’s Parties, Indigenous Peoples and Communities

Holly Fain, Maine Law

Nov. 19, 2024

Leading up to Week 1

My name is Holly Fain; I am in my final year at Maine Law. I have been studying law and community outreach work under the pathways of Environmental and Natural Resources Law, Youth Justice and Policy, Federal Indian Law, and Native American rights. I am a Mexican American (on my mother’s Indigenous side) and Shoshone Native American (on my father’s side), and co-chair of our Maine Law’s Native American Law Students Association.

I am thrilled to be attending COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, with a delegation to follow the negotiation track of the Global Goal on Adaptation and Article 6 drafting and revisions, specifically the thematic targets of qualitative measurements of Indigenous populations, climate impacts, and climate resilience. Under this track, I will be following content related to Indigenous frontline populations, conservation of natural resources, the utilization of Indigenous Knowledge, and the role of cultural heritage. Biodiversity, natural resources, Indigenous Knowledge, and Cultural Heritage are all subtopics of these thematic targets (See RINGO’S Key Issues to Watch at COP29).

While the world’s Indigenous Peoples make up less than 5% of the total human population, Indigenous populations manage and hold tenure over 25% of the world’s land surface and support about 80% of our global biodiversity. Biodiversity enables human and animal survival and with 80% of the world’s biodiversity being protected and stewarded by Indigenous groups, it is crucial that Indigenous populations, leaders, and activists are actively participating in climate negotiations. I want to study this representation and participation, and see what the outcomes will be during Week 1 of COP29.

Additionally, I am compelled to target qualitative and quantitative information to see how financial strategies are being leveraged and modified to support both environmental sustainability and nature-based solutions. I am setting out this Monday, November 11, to see if COP29’s Global Goal on Adaptation (the GGA Framework) or Finance discussions and negotiations are empowering fossil fuel industries and carbon markets or the populations who have experienced harm and vulnerable land rights. My intention was to observe where the money is flowing and if it is empowering emissions reductions and repairing/replenishing the resources and land for frontline populations or not. These components of COP’s Global Goal on Adaptation are rooted in the goals of contributing to sustainable development and ensuring an adequate adaptation response in the context of Article 7 of the Paris Agreement.

Indigenous communities are increasingly under environmental and financial distress. Indigenous People across the world are being disproportionately hit by the impacts of climate change on their ancestral lands. This environmental vulnerability is compounded by their reliance on traditional practices, connection to their land, and economy. Indigenous Peoples’ Knowledge of looking after their land should be at the heart of climate policy-making, but they continue not to be. At the UNFCCC, Indigenous People are not credentialed as negotiating parties, which can severely limit their ability to impact the yearly outcomes of COP negotiations.

From many perspectives of Indigenous populations on the frontlines of oil and gas, hydrogen, CO2 pipeline infrastructure buildout, it is not just the populations who are harmed, but the damage to the Earth is resulting in true loss, and future generations of Indigenous populations are further endangered. At this rate, the future generations will not only be displaced, but continue to decrease.

Nature-based solutions, circular economics, and traditional practices have been a way of life for thousands of years of Indigenous Peoples worldwide. This knowledge is key to climate action and the sharing of it with other communities is vital to the future of global adaptation. Indigenous Peoples hold the potential to be policy guides and leaders in decision-making processes on climate action, yet the integration of their knowledge and practices into international and national programs and policies is not mainstream due to the framework of the UNFCCC. This is appalling to me, yet in a world focused on finance, gains from carbon markets, and rising economic powers, it is not surprising.

The UNFCCC’s Non-State Actors are Mother Earth’s Parties

Indigenous Peoples are not credentialed to participate in climate negotiations, therefore they are not a party to COP negotiations. That said, I am coining these vital groups as EARTH’s PARTIES in my participation at COP. I am not shy, nor hesitant to approach anyone I meet in briefings, press conferences, pavilions, and even negotiation rooms, with this term of art. I hope I further fuel this end of environmental justice, human rights, and COP’s textual progress. This is going to be such a journey–here we go!

After attending a morning Research and Independent Non-Governmental Organizations (RINGO) meeting, I will be meeting with Rutgers University’s Professor of Sociology, Danielle Falzon, whom I was connected to through a RINGO webinar a few weeks ago. She presented information and tips for what to look out for in COP29’s Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) this year. I will be chatting with her about thematic tracks of adaptation, how the UAE framework of texts for adaptation and climate action have evolved since last year’s COP28 negotiation track. I will ask her how the framework is improving the ability to measure progress on the GGA and maintain accountability. These are loaded questions, but walking around the pavilions and having coffee as we chat will make the conversation pretty upbeat, I hope.

**Special gratitude to my family, as they keep up with my Maine Law adventures from their home in Texas. My Mama made me a blazer for my COP29 attendance. She made this for me with a personal touch of symbolism for our Native culture of the South, an emphasis on biodiversity, climate migration, and the fact that like the monarch butterfly, I too, had to make a move from the south to the northeast to fulfill my diverse needs.

Day Three – It’s One Planet

Hailey Rizzo, Maine Law

Nov. 14, 2024

“We are not here to beg . . . We are here to say, ‘it is small island developing states today, but it will be Spain tomorrow or Florida. It’s one planet.’”

– Dickon Mitchell, Prime Minister of Grenada

I attended a small portion of the second day of the Statements of the Heads of State, where I heard (1) the Prime Ministers of Tonga, Sao Tomé, Grenada, and the Cook Islands deliver their national statements. Many of them had the same message: that SIDS contribute very little to global emission levels but face the brunt of the impacts and it is time for operationalization of the loss and damages fund. Prime Minister Mitchell’s statement, however, was different.

Prime Minister Mitchell opened by informing us that for the first six months of the year Grenada experienced a fifteen-year drought, or the most severe water crisis in the last fifteen years. He continued by emphasizing that on the first day of the second half of the year Grenada was hit with a Category 5 Hurricane that devastated the island. In addition of calling for operationalization of the Loss and Damages Fund as many other SIDS did in their opening statements, Prime Minister Mitchell emphasized that the Fund is a “partnership for mutual benefit” because the mitigation and adaptation lessons learned in small island developing states presently can be shared with the rest of the world as it faces impacts from climate change in the future.

Prime Minister Mitchell re-emphasized that climate change is a global issue with global contributors and global impacts. The only solution is collaboration and communication and small island developing states bearing the brunt of these impacts are calling for a mutual partnership to protect their homes and prevent further impacts to the homes of the biggest contributors to climate change. SIDS are at COP29 to effect change, but more importantly to collaborate on a solution.

(1) I observed statements from heads of state from other countries as well, but for purposes of this blog post and my research at COP29 I am focusing on small island developing states (SIDS).

Day Two – What does “Full Operationalization” of the Loss & Damages Fund Really Mean? – Hailey Rizzo, Maine Law

Hailey Rizzo, Maine Law

Nov. 13, 2024

Around 5:00 PM on November 12, 2024, at an event entitled “COP29 Presidency signing ceremony: From Pledges to Action: Full Operationalization of the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage,” Senior Managing Director of the World Bank, Axel van Trotsenburg, and the co-chairs of the Fund for responding to Loss and Damage, Jean-Christophe Donnellier and Richard Sherman, signed the Trustee Agreement and the Secretariat Housing Agreement, as well as the Host Country Agreement with the Republic of the Philippines. But what does this mean?

The Trustee Agreement and Secretariat Housing Agreement designate the World Bank as trustee for the Fund for the first four years as interim secretariat host. This means that the World Bank will be responsible for holding and disbursing funds until there is a permanent home for the Fund. As a trustee, the World Bank has no role in fundraising, deciding on fund allocations, or implementing and monitoring the projects the Fund finances. These responsibilities lie with the Fund Board. The Host Country Agreement means that the Philippines will host the Fund Board, which gives the Board “the legal personality and the legal capacity necessary for discharging its roles and functions.” (1)

While signing these agreements is undoubtedly a critical first step in disbursing funds, this is far from the “operationalization” of the Loss and Damages Fund that I was expecting when entering the signing event. What remains to be decided is how the funds will be disbursed, to what countries, in what amounts, what countries should contribute, how often they should contribute, and how much they should contribute.

Also at the ceremony, Sweden pledged approximately $19 million to the Fund and urged other countries to increase their contributions as well. Additionally, the COP27 and COP28 Presidents were commended for their work in getting the Loss and Damages Fund on the agenda and laying the foundation for the operationalization of the Fund at COP29. In her remarks, the COP28 President, emphasized how quickly the fund was agreed to and commended the Parties political momentum and cooperation. To this point, I want to emphasize that AOSIS has called for a mechanism to pay for loss and damages felt in small island developing states since the early 1990’s, so how quickly was the Fund really “operationalized”?

Finally, in his closing remarks, the Chief Negotiator for Azerbaijan at COP29 stated that “the damage has already been done . . . [but] this Fund represents a lifeline, particularly to our friends in small island developing states.” Although the fund was “operationalized” there remains much to negotiate at COP29, and in the meantime small island developing states continue to face the impacts of climate change.

- Language from the Draft Proposal of the President on Operationalization of the new funding arrangements, including the fund, for responding to loss and damage referred to in paragraphs 2–3 of decisions 2/CP.27 and 2/CMA.4 from Nov. 29, 2023. Available at https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cp2023_L1_cma2023_L1.pdf

Talking About What to Talk About

Prof. Anthony Moffa, Maine Law

Nov. 12, 2024

Day 1 of COP29 was marked by an unprecedented delay of the opening plenary. The plenary began as scheduled at 11AM and then promptly ground to a halt just a few items into the agenda. Ironically, the hold came in getting an agreement on item “2(a) – Adoption of the Agenda.” Then, we waited. For hours. The delays came like in an airport, first an hour at a time, then thirty minutes at a time. And finally the plenary reopened at 8PM.

It turned out there were two agenda-related issues holding things up. There had been a very late proposal by China and some others to add unilateral trade restrictions to the agenda. The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, slated to go into full effect in just over a year, surely prompted this. Ultimately, the COP Presidency scheduled consultation on this topic during week one, not giving it a full agenda slot, but also not ignoring it. The other agenda issue had to do with some arcane cross-referencing between finance and global stocktake (GST) items. Paragraph 97 of the GST set up a work programme to review outcomes and happened to be physically located under the financing heading in the document. Some countries took contended that only finance outcomes should be the subject of the work programme, others interpet the mandate more broadly. The landing zone at 8PM kept the programme under finance on the official agenda with a footnote that says its placement there does not preclude discussion of any outcomes.

This was interesting and frustrating for all delegations, but even more so for our UMaine delegation because I had been tapped to represent the Research and Independent NGOs coalition (RINGO) at the opening plenary. As such, I prepared a statement to deliver during the two minutes of time our coalition was allocated to address the chairs and all of the parties. I am pictured below waiting for my opportunity to speak.

Eventually, I should have the opportunity to deliver the statement on behalf of RINGO to a reconvened session. When that happens is unclear. Regardless, my words on behalf of RINGO have been entered into the record as a written statement. They are reproduced below for ease of reference.

RINGO Constituency Statement for Combined Opening Plenaries COP29/CMP19/CMA6/SBI61/SBSTA61 11 November 2024

Thank you, Chairs, for the opportunity to address this opening plenary on behalf of the Research and Independent NGOs, or RINGO. My name is Anthony Moffa, and I am a professor and associate dean at the University of Maine School of Law.

Backed by science, COP28 ended with parties agreeing for the first time to “transition away from fossil fuels in energy systems.” And yet, since then, there have been documented rises in both fossil fuel use and exports.

During this COP, we urge parties to continue to center science in decisionmaking and consider the ways our research community can support a transformational trajectory for a new renewable energy portfolio that ensures the security and resilience of people and nature.

As countries are currently engaged in establishing revised nationally determined contributions in response to the recent global stocktake, we urge parties to engage with diverse knowledge networks in establishing and enacting feasible and impactful solutions.

Fifteen years ago in Copenhagen, developed country parties committed to a collective goal of mobilizing 100 billion us dollars per year for climate action in developing countries. As parties sit down to set a more ambitious New Collective Quantified Goal at this COP, we emphasize the importance of acknowledging the needs of developing countries in three areas.

On mitigation, the rapid adoption of fossil-fuel free energy and transportation solutions will depend on continued innovations in technology, and functioning mechanisms for the transfer of that technology as well as methodologies for properly counting removals and avoidance under Article 6. The transition to renewable energies has already begun, as RINGOs we offer our expertise in navigating the continuously complex decision-making space.

On adaptation, parties will look to experts, including many RINGOs, to help define the indicators necessary to monitor progress towards the Global Goal on Adapation’s seven thematic targets. To implement new indicators swiftly and accurately in developing countries support from developed countries will be necessary.

Finally, this COP is situated in a unique time, where funding mechanisms are evolving and more necessary than ever before. The newly established loss and damage fund will need to be operationalized. At the same time, scaling up climate finance for mitigation, particularly renewable energy development, must be addressed at COP29. Furthermore, as the IPCC proves, a significant gap remains between current finance and what is needed to meet Paris Agreement goals.

At COP29, we urge Parties to act with the urgency and scope that science and research dictates is required. This involves rapidly increasing financing ambition through all available means across mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage.