COP28

The UAE Consensus – Misleading & Underachieving

By Natalie Nowatzke, J.D. Candidate 2024, University of Maine School of Law

December 13, 2023

As soon as I landed in Toronto, my layover between Dubai and Boston, I started receiving notification after notification on my phone. A deal had been reached at COP28, resulting in what is called the UAE Consensus. The COP Presidency is calling it “an enhanced, balanced, and historic package to accelerate climate action” as it contains “an unprecedented reference to transitioning away from all fossil fuels.” Other news outlets have referred to the decision as a “landmark,” “historic,” and “groundbreaking” deal.

Although the UAE Consensus is the first time an agreement of this kind explicitly mentions fossil fuels, it is not the win that many want us to believe. The boasted language regarding fossil fuels comes from the final version of the Global Stocktake, and reads as follows:

Further recognizes the need for deep, rapid and sustained reduction in greenhouse gas emissions in line with 1.5 °C pathways and calls on Parties to contribute to the following global efforts, in a nationally determined manner, taking into account the Paris Agreement and their different national circumstances pathways and approaches:

. . .

(d) Transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade, so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science.

While this agreement containing “fossil fuels” in the text is a step forward, the adjectives being used to describe it are contrary to science and a disservice to the public.

The science is clear and has been for decades. Climate change is causing unprecedented global temperature rise, and 2 °C of warming is a “critical threshold” for abating severe and irreversible effects. Global surface temperature has already risen 1.1 °C, with global emissions continuing to increase. Even worse, we know that the production and burning of fossil fuels is the largest contributor to this warming, and “CO2 emissions from existing fossil fuel infrastructures without additional abatement already exceed the remaining carbon budget for limiting warming to 1.5 °C.”

Thus, this language is too little, too late to meaningfully mitigate climate change. The use of vague verbs, such as “calls” and “transitioning” are practically meaningless in the face of impending disasters from climate change. The audacity to say, “in keeping with the science,” while ignoring the pleas of countless scientists, and those of us that are capable of listening to them, is particularly infuriating. The Earth cannot withstand this pace of crawling progress, especially in this critical time.

Although I am frustrated and disappointed with the adopted Global Stocktake, I am not leaving COP28 with only these emotions. I found motivation to continue to advocate for the necessary changes we need in the face of climate change all around me at COP28. We had the opportunity to meet with Tzeporah Berman, founder of the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty, Dr. Susanna Hancock, a fierce climate researcher and policy specialist, and many U.S. officials who are working to better U.S. policies. We listened to panels that presented innovative policy solutions and new technology, from advocates, leaders, and scientists from all around the world. Particularly inspiring was watching and hearing from countless youth as they bravely advocated for our future. Although I leave disappointed with world leaders who refuse to do what is right, I remain motivated by my colleagues working towards the same future I envision.

Beyond the Numbers: Connection at COP28

By Ashley Brown

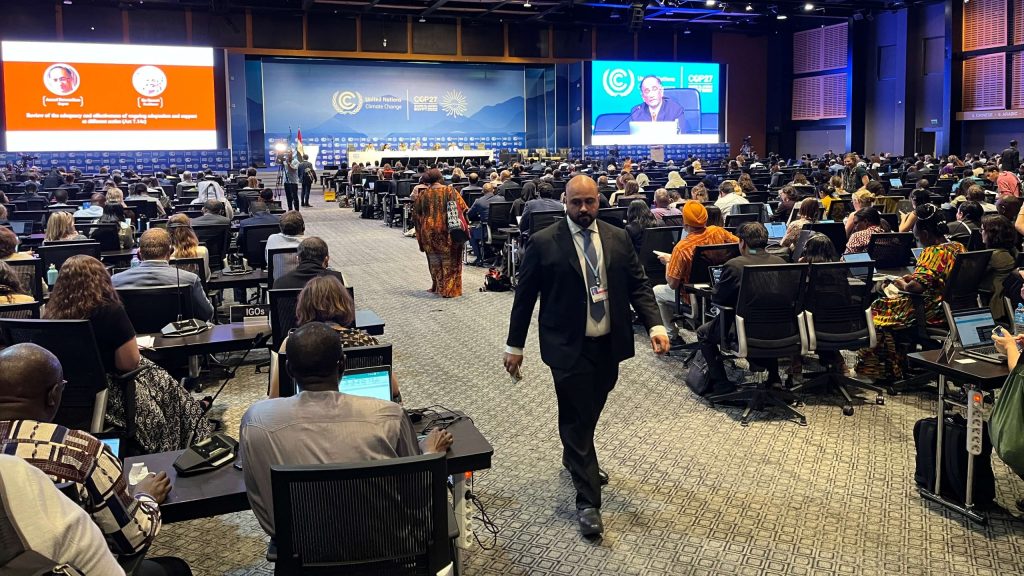

For better or for worse, watching people walk by at COP28 there is only one word to describe people’s faces: determined. Whether it be phone calls while power walking or on-the-move networking not a single second is wasted. I saw someone with their phone and two laptops open while eating their lunch, and another dictating to their phone while handwriting notes about something else. The dedication is inspiring– and intimidating.

It’s just so easy to feel overwhelmed with the seemingly endless options and barriers to tackling climate change: being surrounded by some of the world’s best and brightest minds on climate change feeds into these feelings of confusion and inadequacy. There is no clear path, no crystalline choice, no obvious answer. But, there is each other. When we’re attempting to quantify everything from GHG emissions to our goals we accidentally leave out connection, something so vital to our existence. When we wear our hats of negotiators and delegates, we often talk about data and things that are easily quantified.The negotiations are clinical. Rooms are colder, chairs spaced further apart. Emotion and human connection feel removed. Numbers can be quite compelling, but always a little detached. Stories connect us, allowing us to understand each other in ways statistics and facts can’t. At the heart of the climate crisis is people: we need to be able to connect to each other in order to solve this as fast as we can.

I observed a discussion during a pavilion event that was neither hopeful nor full of despair, but about what it means to be a person here at COP28. Not an observer, a party member, a student, a sanitation worker, or a head of state—just a person trying to live in a world that often feels like it’s falling apart. The two talked about how they were from Sudan and Somalia, but raised here in the UAE. In particular, they focus on their connection to the sand that surrounds us.

Deserts tend to have certain narratives surrounding them: arid, dry, empty, and inhospitable. Picture the yellowish filter Hollywood puts on every movie set in the Middle East.

They called it “the washing,” speaking out against these narratives and the subsequent weaponization of the desert against migrant groups in Africa and their own communities. They said it feels wrong to view sand in this way, knowing it has been villainized. Erasing the landscape of their youth. Sand reminds them of the beach, playing as children, and home. The two expressed sorrow at the fact that their childhood memories are being replaced with fears of climate change and overconsumption as Jumeirah beach has been gentrified, and the desert encroached by the city.

One of them segued into discussing the imposter syndrome they feel here at COP28, saying “I’m just trying to tell my story” but that it often feels like everything overshadows her as an individual. Agreeing, her co-host dives into some of her own feelings regarding COP28, most notably anger and frustration. “We’re just kids,” she said, her voice almost cracking,“We’re not supposed to be trying to save the world- but it’s what we were stuck with.” Chiming in, the other girl says that “It’s okay to say ‘I don’t know’– there is so much general confusion and multiplicities of everything, it’s all intricate and complex and just see how you can navigate around them.” If we knew the right way to solve climate change all of us would agree, but the only thing we agree on is that Climate Change is a problem. How to solve it is a whole 70,000-different-people story that has already taken almost thirty years. There is no one ‘silver bullet’ solution so we must wade through the uncertainty to find our way out of the climate crisis. It’s okay not to know, to not agree– but it’s not okay to not try.

Connecting, inspiring hope, and telling our stories is working to fight the climate crisis, even if it may not be as quantifiable as hard data.

The Global Stocktake Just Enough to Avert Freefall

As you may recall, the negotiations at COP28 circled around two important concepts – the 1.5°C target and the attachment to fossil fuels. Negotiations on these items already seemed intractable at the beginning of the week. Then, a letter from OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) leaked, and the drama boiled over.

The letter fiercely opposed “phase out” language on fossil fuels, citing what it called “undue and disproportionate pressure against fossil fuels.” Even more, it made clear that OPEC countries “proactively reject any text or formula that targets energy, i.e. fossil fuels, rather than emissions.” In other words, no agreement on fossil fuels could apparently appease OPEC.

In the fallout over the weekend, the COP President convened a convened a majlis – an Arabic term that refers to a sitting room or a council in many Islamic countries. President Sultan Al Jaber invited the high-level ministers from every party to sit in a circle around him to speak “heart to heart.” In those conversations, stark lines emerged, somewhat tracking the divide implied by the leaked letter – oil-producing countries wanted to focus on emissions, not fuel sources.

The day after the majlis, the COP Presidency produced a draft agreement that seemed to take the side of OPEC countries. It included no real commitment on fossil fuels. Nations and civil society reacted harshly. With COP28 in the waning hours, a sense of impending doom lingered. With that gloomy uncertainty in the air, our delegation departed Dubai. And then COP28 went into overtime, and the parties somehow pulled a small victory from the jaws of defeat. Preserving a glimmer of hope for global climate governance and multilateralism more broadly.

Let’s look at the text of that final agreement on the Global Stocktake a bit more closely, focusing on the two key issues.

On the 1.5°C target, the agreement mentions it more than a dozen times. The most significant of which appear in paragraphs 3-5, reading (emphasis added):

- [The Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement . . .]

o Reaffirms the Paris Agreement temperature goal of holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change;

o Underscores that the impacts of climate change will be much lower at the temperature increase of 1.5 °C compared with 2 °C and resolves to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C;

o Expresses serious concern that 2023 is set to be the warmest year on record and that impacts from climate change are rapidly accelerating, and emphasizes the need for urgent action and support to keep the 1.5 °C goal within reach and to address the climate crisis in this critical decade;

Looking at the above language, only one of the highlighted phrases even arguably looks like a binding commitment by nations. And that commitment is only to “pursue efforts” to limit increase to 1.5 °C.

On fossil fuels, the final agreement at least said something; OPEC was unsuccessful in keeping it out of the document entirely. However, neither “phase out” nor “phase down” language were used. Instead, the final text “calls on parties to contribute to”:

- Transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade, so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science.

Arguably, “transitioning away” from something is the same thing as phasing it out, so, in a general sense, the language reads strong. However, upon closer inspection, the reader will note that there is no binding language preceding it.

The best and worst features of international law were on display at COP28. Countries from across the globe recognized a common problem and resolved to work together to address. At the same time, the system designed to operationalize that ongoing commitment depends on consensus and moves slowly and rarely realizes its lofty ambitions. At the end of the day, we landed in a familiar place – compromised, watered down language about what should be done. At least we have something; multilateralism (and the planet) will live another day.

A high seas treaty may not be as UNCLOS as it seems

Dec 11, 2023

By Geetanjali Talpade, JD Candidate ‘24, University of Maine School of Law

Both domestic and international environmental laws, while relatively recently conceived (the first major U.S. legislation, the National Environmental Policy Act, was passed in 1970), overall pre-date the common modern understanding of climate change. Environmental activism has historically focused on preservation of the environment and biodiversity against human impacts like pollution and industrialization. At first glance, climate change law is aligned with those goals: to protect the environment from harmful human activity – previously primarily pollution, now CO2 emissions resulting from reliance on fossil fuels. But the tools that environmentalists have thus far relied on may be ill-matched to address climate change.

In the international realm, this becomes glaringly apparent when looking at Article XII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), adopted in 1982. UNCLOS (often called “the constitution of the sea”) establishes national jurisdictional lines and regulates human activity in the ocean, obligating states to, inter alia, protect and preserve the marine environment. These jurisdictional lines, however, end 200 nautical miles from the shore – leaving the high seas beyond national jurisdiction and thus unprotected.

This is especially a problem when it comes to climate change. The high seas themselves comprise ⅔ of the world’s oceans, covering almost 50% of Earth’s surface and representing an estimated 95% of all occupied habitat on our planet. They generate 50% of the oxygen we need, absorb 25-30% of excess CO2, and capture 93% of excess heat generated by fossil fuel emissions. They capture and store half a billion tons of carbon (or $145 billion) annually through a process called the biological pump, which (perhaps obviously) relies on biological organisms from phytoplankton to whales to sequester carbon into the deep ocean. The high seas (and their inhabitants) are the Earth’s largest carbon sink, and a significant tool for climate mitigation. They are also highly vulnerable to climate change, climate interventions, and direct human disturbance; as Natalie highlights, rising global temperatures spell dire consequences for the ocean, its biodiversity, and coastal communities. And the high seas’ biodiversity present complex governance challenges: they have high levels of heterogeneity and endemic species, with mutualistic species tending towards great longevity and late maturity. This means that each input triggers a range of responses across species, with significant ecological ripple effects on the more regulated national waters.

The U.N. High Seas Treaty, also known as Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Treaty, considers these fundamental complexities to close the jurisdictional gap. The BBNJ, an international legally binding instrument signed by 84 U.N. Member States in September of this year, is the effort to “ensure the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction, for the present and in the long term, through effective implementation of the relevant provisions of the Convention and further international cooperation and coordination.”

Today’s panel event “How Can International Ocean Law Assist States to Meet Their Climate Change Obligations?” convened science (Lisa Levin, deep sea biologist), law (Nilüfer Oral and Cymie Patyne, law professors), advocacy (Rebecca Hubbard, Director of High Seas Alliance), policy (Javier Davalos, attorney with Interamerican Association of Environmental Defense), and diplomacy (Walter Shuldt, Chief Negotiator for Government of Ecuador) to examine the BBNJ’s structure and potential impact on climate change.

The BBNJ has four key elements:

- Marine genetic resources (MGRs), including the fair and equitable sharing of benefits – Part II (Art. 9-16) – MGRs include physical genetic materials “of actual or potential value.” Currently only a limited number of vessels can collect organisms to assist in development and commercialization of products (including medicine, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and food supplements). For the first time, companies would be required to pay for the use of genetic resources obtained from the high seas. The companies are then required to share both the monetary and non-monetary (research, technology, capacity-building) benefits. The access and benefit-sharing committee, which would establish benefit-sharing guidelines, would be elected based in part on qualifications, gender balance, and geographic distribution (including small island & landlocked developing states and least developed countries). Presumably the recipients would be developing countries, out of recognition of their limited economic capacity to conduct independent research, but the specifics are yet to be determined. Notably, Part II, Art. 10 specifically exclude fish from the definition of MGRs, despite the essential role fish and fishing play in marine ecosystems (fishing companies have overexploited more than ⅓ of the ocean’s fish stocks, both within national jurisdiction and in the high seas). Perhaps predictably, the fishing provisions and the fair and equitable benefit-sharing were the two major points of dispute during negotiations – with the inclusion of non-monetary benefits resulting from efforts from developing states.

- Area-based management tools (ABMTs), including marine protected areas (MPAs) – Part III (Art. 17-26) – ABMTs would establish MPAs to achieve long-term conservation and sustainable use goals (as long as they do not infringe on any areas within national jurisdiction). In addition to addressing biodiversity and strengthening cooperation between stakeholders, ABMTs are intended to support socioeconomic & cultural objectives and developing states’ abilities to manage MPAs. After consultation with relevant stakeholders (which include State bodies, civil society, the scientific community, the private sector, Indigenous Peoples, and local communities), the ABMT is adopted when consensus is reached (when possible), or by ¾ majority of present parties. There is an opt-out provision for objecting parties within 120 days after voting, but the decision is otherwise binding for all treaty parties.

- Environmental impact assessments (EIAs) – Part IV (Art. 27-39) – EIAs are intended to evaluate the impact of the proposed activity on marine biodiversity and ecosystems (especially when the activity may have more than a minor effect on the marine environment or the effects of the activity are unknown/poorly understood). Parties would be obligated to conduct an EIA in two circumstances: (1) for planned activities in the high seas that may have potential impacts on the marine environment; and (2) for planned activities within national jurisdiction that may negatively impact the high seas. Parties may additionally consider conducting strategic environmental assessments (SEAs). SEAs are more holistic, evaluating long-term environmental protection – especially relevant when measuring the costs and benefits of conservation with the long-term costs of worsening climate change. However, parties are not obliged to conduct an SEA, and the specific mechanics (and exhaustiveness) of EIAs are dictated by the state’s domestic policies. Additionally, EIAs have no ability to control the eventual outcome – they merely force decision-makers to include environmental values in their final resolution.

- Capacity building and the transfer of marine technology (CB&TMT) – Part V (Art. 40-47) – the principle of CB&TMT is embedded throughout BBNJ (and, incidentally, throughout COP28), but receives a stand-alone part, underlining its significance. CB&TMG is intended to make the treaty “future proof” by encouraging exchanging information, building awareness, and strengthening infrastructural, financial, and institutional frameworks. Because of the inherently unpredictable nature of technology development and state needs, this provision was drafted to be flexible. It lacks a specific definition of capacity building in Part I Article 1, opting instead for a broad non-exhaustive list of capacity-building initiatives. Parties are obligated to cooperate in CB&TMT, which would be a “country-driven, transparent, effective and iterative process that is participatory, cross-cutting and gender responsive.” CB&TMT is focused especially on developing and least developed states.

As you can see, questions inevitably remain – the exclusion of fish and fishing; whether EIAs’ have the ability to halt destructive human activities while encouraging climate change mitigation efforts; would the United States (who, despite recognizing it as customary international law, has nevertheless not ratified UNCLOS) be a party and how that would impact BBNJ’s effectiveness; what to do about marine carbon dioxide removal technologies and deep-seabed mining for minerals used to develop renewables; and so on.

But, as Cymie Payne emphasizes, 1.5° is too warm for many marine ecosystems: time is not on our side, and the BBNJ would be a significant win. The BBNJ would make it possible to protect 30% of the oceans by 2030 (as part of the 30 by 30 goal). It is guided by, inter alia, the polluter-pays principle, the rights and knowledge of Indigenous Peoples, scientific data, and recognition of the special interests and circumstances of developing and least developed countries (Part I, Art. 7). Gender balance and responsiveness is included in several provisions (but not enough, according to me). Greenpeace calls the BBNJ “the biggest conservation victory ever.”

The BBNJ requires 60 countries to ratify by September 2025 to go into effect – it currently has zero (the 84 countries that have signed the treaty are merely indicating a willingness to eventually ratify. Individual countries must ratify through their own domestic legal and legislative processes.). On the other hand, it has been open for ratification for barely 2 months, already with significant support from the EU. It has taken two decades for 190 countries to agree on the final text (the High Seas Alliance has been working since 2011). International law inherently moves slowly; consider how long it takes for domestic U.S. policy to move forward. The race for ratification is on – it might just be a case of the tortoise, not the hare.

Elephants in the Room

December 12, 2023

By Bryant Wolff, J.D. Candidate 2024, University of Maine School of Law

Much like our planet, COP28 is heating up; while Loss and Damage has come to a close, the Global Stocktake, Global Goal on Adaptation, climate finance, and much more are still in the midst of negotiations. Questions around including language like “phase out” or “phase down,” “abated” or “unabated,” “common but differentiated responsibilities” still remain. Most of us still here at COP28 are running on fumes but Parties will need to push through, have another cup of coffee, and accomplish meaningful progress on negotiations. However, not all here share the view that language around phasing out, or even phasing down, fossil fuels is a priority at COP28.

Those at the U.S. Center at COP28 were joined by a panel of Republican House Representatives which included Rep. Kelly Armstrong (N.D.), Rep. Earl Carter (GA), and Rep. Marienette Miller-Meeks (IA) to discuss conservative perspectives on reducing emissions within the United States. Statements focused less on what still needs to be done to develop the clean energy economy of the United States, and more on patting ourselves on the back for what has been done so far. Even though fossil fuel companies have continued to reap more and more profits each year, the Republican Representatives showed support regardless, citing marginal emission reductions. Representative Carter touted that fossil fuel companies haven’t done a good enough job telling people what a good job they’ve been doing lowering their emissions; a stark contrast from the thousands here at COP28 calling out fossil fuel companies and seeking a clean energy future.

Representative Carter of Georgia stated, “it’s about emissions not the source,” but in the face of the world’s greatest challenge, the panel’s clear support for fracking, nuclear energy, carbon capture sequestration (CCS), and “future technologies” shows that they would rather address the effects than root of the problem. Justifications for the continued use of fossil fuels were security, affordability, and reliability, typical arguments for those unwilling to stand with the world in the fight against climate change. The conservative panel pointed fingers and emphasized that the rest of the world needs to step up and that climate change is a global problem, not a United States’ problem, but this ignores the reality of historical emissions and common but differentiated responsibilities in addressing our climate crisis.

Statements in support of producing the cleanest fossil fuel in the world felt contrarian to the purpose of COP28 amongst the University of Maine Delegation. At the world’s largest climate change conference, States, policy makers, advocates, and scientists have spoken louder than ever in support of an end to the addiction to fossil fuels. While the extent of meaningful action to addressing climate change at COP28 is unclear, with so many focused on the future, the words of House Republicans feel as much a fossil as the fossil fuels we seek to phase out.

Hungry for Action at COP28

Charity Zimmerman

Graduate Student School of Policy and International Affairs and School of Economics,

NSF One Health and the Environment Research Trainee

Dec. 12, 2023

Food is a hot topic at the COP this year, and not just because many of the lunch venues have 20-minute wait times outside, under the blazing Dubai sun. A central focus of this year’s summit is on sustainable agriculture, resilient food systems and climate action. Various sources attribute between 10-30% of all global greenhouse gas emissions to food systems, with the single largest source of methane emissions coming from the agriculture sector (in large part due to livestock), and the third largest source coming from food waste (due to the anaerobic breakdown of organic matter). There has been a recent emphasis on the climate impacts of methane, as it is one of the most potent greenhouse gasses. Although methane dissipates from the atmosphere more rapidly than carbon dioxide, according to the Environmental Defense Fund, it has roughly 80 times the warming power of CO2 once it enters our atmosphere. It is for this reason that many countries at the COP have asserted that addressing methane emissions is the fastest avenue for slowing warming temperatures and ensuring that we stay under the 1.5-degree Celsius goal set forth by the Paris Agreement.

The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) is expected to launch a road map for countries to help meet their climate goals through agrifood solutions on December 10th, the thematic day on food, agriculture, and water. Based on announcements and sessions up to this point in the summit, we expect to see the FAO call on developed countries to 1) increase in financing of novel and regenerative agriculture projects and 2) move toward alternative protein sources, in addition to reducing meat consumption. In the spirit of this emphasis, an impressive two thirds of the food offerings in the venue are entirely plant based.

While bringing attention to the climate impacts of agriculture, and especially methane, is important, some attendees at COP have questioned whether this year’s increased attention on food systems is simply an attempt to detract from the pressing need to decouple from fossil fuels. This year’s summit is hosted by the United Arab Emirates (UAE), one of the largest oil-producing countries. Emphasizing alternate avenues of GHG emissions may be a strategy for oil companies and their allies to continue their business-as-usual approach. However, the US agreed early in the summit to call on oil and gas companies to reduce methane leaks across their systems to “near zero” by 2030, which is a step in the right direction.

The United States Special Presidential Envoy for Climate and former Secretary of State, John Kerry, led a Global Methane Pledge Ministerial, where ministers from several countries solidified their commitments to deliver on the goal to cut methane by at least 30 percent by 2030. The Global Methane Pledge addresses methane across three key sectors – agriculture, waste, and oil and gas. Several representatives, including Kerry, emphasized that although cutting methane will be necessary for addressing climate change goals, this is not a “get out of jail free” card for the fossil fuel industry as we still need to progress towards decarbonization if we hope to maintain a livable planet.

Climate-friendly innovations in the agriculture and food-security sectors are impressive and ongoing, with sessions across the summit highlighting an extensive array of projects. I heard talks discussing agroforestry in Brazil, lab-grown meat in South Africa, and agrovoltaics (building solar farms on the same land as agricultural fields) in Egypt in addition to observing several informal consultations on implementing the Sharm el-Sheikh joint work on climate action on agriculture and food security. Exciting commitments are coming out of COP28, but as noted in the closing of the Global Methane Pledge Ministerial, announcements don’t reduce emissions. We must continue to assess our progress on our commitments through processes such as the Global Stocktake.

I look forward to more exciting news and ideas that are sure to emerge by the end of the conference, especially on December 10, and hope that what many are calling the “Food COP” will open the hearts – and stomachs – of us all as we work toward mitigating and adapting to climate change.

Ocean Action Day at COP28

By Natalie Nowatzke, J.D. Candidate 2024, University of Maine School of Law

December 9, 2023

Today was Ocean Action Day at COP28, recognizing the importance of the ocean in addressing the climate crisis. Rising greenhouse gas emissions are directly linked to severe consequences for the ocean, including sea level rise, marine heatwaves, loss of biodiversity, and acidification of the ocean. These changes alone are devastating for the health of the ocean, but the impacts do not stop there. The continued decline of the health of the ocean will particularly impact coastal communities across the world.

Prior to everyone convening in Dubai, the COP28 Dubai Ocean Declaration was published with 124 signatories. This Declaration specifically called “on world leaders to support and foster efforts to greatly expand and improve ocean observations worldwide to provide a basis for understanding ongoing natural and anthropogenic change and for planning mitigation and adaptation strategies, with a particular emphasis on building capacity in developing nations and on expanding coverage of under-observed regions.”

The week two University of Maine delegation started Oceans Action Day as we start most, at the Research and Independent Non-Governmental Organizations (RINGO) morning meeting. We had the opportunity to hear from Dr. Miriah Kelly, Assistant Professor of Environmental Science at Southern Connecticut State University and the leader of the RINGO Ocean Group. She spoke briefly about the many ocean-climate nexus issues, as well as the COP28 Dubai Ocean Declaration. Dr. Kelly noted that following this Declaration, this key question remains: “How do we do this justly, fairly, and equitably?”

I also had the opportunity to attend an event titled “Taking Stock of Climate Action: Land Use & Ocean and Coastal Zones” which consisted of both individual speeches and two panels. The first panel was titled the “Hiking Panel” and focused on land based actions, and the second panel was the “Surfing Panel,” focusing on ocean based actions. These panels were tied together with common themes, as well as the opening statement of H.E. Razan Al Mubarak. She noted that scientists and climate experts “often operate in isolation. However, when considering nature, we are all dealing with a single, interconnected nature.” One especially important theme throughout both panels focused on the need for inclusion of and the placement of trust in Indigenous Peoples from the very beginning of processes.

Looking to the near end of COP28, I am eager to see final documents and hope for substantial language acknowledging and addressing the ocean. All positive climate action ultimately benefits the ocean, but it is essential that the ocean begins to receive the space and recognition it deserves throughout climate action of all levels.

COP28 Week 2 Begins with Lofty Ambitions, and Serious Questions of International Law

Anthony Moffa, Professor of Law, University of Maine School of Law

Dec. 9, 2023

During the rest day, the University of Maine delegation regrouped and welcomed a new batch of delegates from Maine Law. Three third-year law students – Geeta Talpade, Natalie Nowatzke and Bryant Wolff – will join me in representing our university at what looks to be a short, busy week two of COP28.

After an unprecedented efficient start to COP28 on Loss and Damage, some of the most important issues on this year’s agenda remain open as week two begins. The Global Stock Take has taken center stage as home of more than a few of those contentious points – like how to address continued fossil fuel development and use (phase out versus phase down and abated versus unabated) and how to reassert the 1.5C target (as an aspiration or a binding commitment). In another part of the negotiations, parties have been struggling with how to operationalize Paris Agreement commitments to emissions reduction credits and international carbon markets, which will be increasingly important as recent net zero commitments are triggered.

COP President Sultan Al Jaber recognized the challenge ahead as he opened the second week of COP28. He set an ambitious schedule for the weekend, featuring an overarching informal meeting of ministers to consult the presidency on the fossil fuels commitments throughout the agreement.

Of particular interest to Maine, the Canadian environment minister has been tasked with taking on a leadership role, particularly with respect to the increasingly comprehensive Global Stock Take negotiations. Those negotiations have been thus far even more contentious than expected and produced draft texts that, as described by Simon Stiell, the United Nations Climate Change Executive Secretary for Climate Change, reflect many lowest denominator positions.

He went on to emphasize: “If we want to save lives now, and keep 1.5 within reach, the highest ambition COP outcomes must stay front and center in these negotiations.”

In the evening, former French prime minister and COP21 president Laurent Fabius made clear that in his view, we are not on track for for 1.5C and that he has communicated to the COP28 president that there needs to be an understanding that fossil fuels must be replaced by renewables.

Sure enough, late in the afternoon an updated draft text for the Global Stock Take came from the newly appointed ministers. At 27 pages, it was lengthy and comprehensive, with many options for some of the most controversial issues. Word spread around Dubai Expo City that the Global Stock Take agreement could play the role of the cover document for COP28. As the lawyers in the delegation, our group discussed how such a move might impact the binding nature of any commitments made in the Global Stock Take. Generally, such cover decisions in international treaties function like preambles do in domestic law – they carefully state lofty aspirations without imposing obligations. If COP28 sets the precedent that stock-taking belongs there, it could undermine the ability to hold countries (and the world) to the commitments they make under the Paris Agreement.

Tellingly, on the question of fossil fuels, the draft presented four options: two that used unqualified “phase out of fossil fuels” language, two that used “phase out of unabated fossil fuels.” A late evening meeting featured heads of country delegations responding to and commenting on the new text. Unsurprisingly, it was clear that agreement was still quite a distance away. More to come as the negotiations evolve.

The New Loss and Damage Fund–Climate justice or just another fund?

By Nicholas R. Micinski, Assistant Professor of International Affairs and Political Science

Dec. 5, 2023

The Loss and Damage Fund was officially operationalized on the first day of COP28 in Dubai. This was long awaited, and hard fought for, but is lacking in scale and specificity.

The Loss and Damage (L&D) negotiations emerged from calls for climate justice by the Global South and civil society nearly 30 years ago. While mitigation is supposed to prevent further climate change and adaptation is intended to help countries cope with current climate change, Loss and Damages acknowledges that there will still be devastating impacts no matter the level of mitigation and adaptation efforts. For some, Loss and Damage was intended to fill this gap and compensate countries on the frontline of the climate crisis for damages to their infrastructure and culture–particularly because those who have polluted the least are hurt the most by climate disasters. For others, though, L&D encapsulates all potential impacts of climate change and the need for risk management and more adaptation planning. In contrast to adaptation funding, Loss and Damage was supposed to function differently because of these principles of historic responsibility, liability, and compensation.

Years of contentious negotiations ensued with developing states arguing for climate reparations, while rich, developed governments refused any mandatory contributions or financial liabilities. In 2013, the COP established the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage to support cooperation on early warning systems, emergency preparedness, slow onset events, risk assessment, insurance, non-economic loss, and resilience. However, the 2015 Paris Agreement asserted that loss and damage “does not involve or provide a basis for any liability or compensation” [Decision 1/CP.21 – III.51]. Since then, the US and EU have pushed an insurance approach and argued that countries like China and rich Gulf states should be excluded from benefiting from L&D funding.

Last year, in a landmark agreement, countries agreed to establish the new L&D fund but did not operationalize the details at COP27. Instead, states negotiated at the intersessional meetings and made remarkable progress in just a few months.

The new fund will be hosted at the World Bank for four years, after which it could transition to an independent entity. There will be 26 governing board members: 14 from developing countries and 12 from developed countries. This means that poorer countries outnumber the rich—an important long-term win for the Global South. But they agreed to several conditions to make sure the fund is not the same as all the other World Bank funding: eligibility criteria for countries will be set by COP not the Bank, and will include all developing countries and their subnational entities as well as any countries that are not members of the World Bank. The agreement also allows for less traditional implementing agencies besides the usual suspects like UN agencies or development banks. Funding could come in the form of direct budget support for national or subnational governments, small grants to civil society like indigenous groups or climate migrants, or rapid disbursement grants.

As of now, the money will come from voluntary pledges. Within a few days, some $730 million was pledged; notably $100 million from UAE, $100 million from Germany, £60 from the UK, €100 million from France and Italy each. The US only contributed $17.5 million; opting instead to pledge $3 billion to the (significantly less controversial) Green Climate Fund.

The 2015 Paris Agreement established a system of voluntary pledges for cutting emissions and donating to climate finance, hoping to rally broad participation. But it remains just that—voluntary. The current pledges are in the millions but the need is billions or trillions each year. One estimate suggested that $400 billion each year would be required and the need is only growing. The scale of donations is simply not enough.

Another concern is that the LD fund should be additional funding–not reallocated or greenwashing other financing. Diann Black-Layne, Ambassador for Climate Change for Antigua and Barbuda explained to other representatives from developing countries: “Loss and damage will not solve your problems. They have moved money from the Green Climate Fund and the other funds. It’s the same funds.”

But there are more interesting and perhaps revolutionary proposals. The UN Secretary General, António Guterres, proposed taxing fossil fuel companies to both contribute to the fund and disincentivize emissions. Mia Mottley, the Prime Minister of Barbados suggested a similar approach: “When you take $200 billion from oil and gas, $70bn from international shipping, another $40-50bn from international air travelers and a financial transaction tax, we have a dedicated source of funds, not just for #LossAndDamage but to build resilience.” Others suggested debt forgiveness or debt swaps as another way to increase the scale of the fund’s impact. Prime Minister Gaston Browne of Antigua and Barbuda argued that voluntary pledges were not enough—instead his county could pursue legal (and financial) accountability in courts.

Clearly, the new fund is a win for developing countries and a big step for the Loss and Damage agenda. But critics are concerned that the L&D fund will be co-opted into just another pot of climate finance by diluting the principles of climate justice.

Taking Stock of Collective Progress

By Cindy Isenhour

Dec. 2, 2023

Parties agreed in Paris to “take stock” of their collective progress on the goals of the Paris agreement every five years. The process, called the global stocktake or the GST, is intended to increase ambition over time by ensuring that parties reflect on collective success and, perhaps more importantly, gaps that must be addressed in order to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement. The outcomes of the GST are intended to send a clear signal about the urgent nature of increasing climate ambition and to inform the next round of country pledges (due in 2025 for the period of action between 2030-2035). The GST has therefore been described as the “ratchet mechanism” of the Paris Agreement, the “key to making it all happen” or more skeptically, “a global experiment in peer pressure”.

However defined, this year’s conclusion of the first GST has garnered considerable attention from negotiators and observers alike. While it has often been difficult as an observer to secure a spot in the room, it remains clear that negotiators in Dubai are hard at work trying to agree upon the outcomes and messaging of a three year process that included the collection of more than a thousand input documents and hundreds of contact hours (For more information about the GST process, see this open source infographic explainer published in Nature Climate Change).

The co-facilitators of the GST worked overnight the first day of the conference to produce a “zero draft” of the GST outcomes. Collectively negotiators spent nearly 8 hours discussing the draft text throughout the second day of the negotiations. Observations of party interventions suggest there are important areas of widespread consensus, and that there are definitely a few key sticking points that will require more prolonged and difficult discussions to reach a workable solution.

First, the good news. There is widespread consensus among parties that the Paris Agreement is working and has had some considerable successes. Parties recognize that warming projections have been revised downward due to Paris actions to date. However, parties also recognize that they have collectively fallen short of the Paris goal to limit warming to “well below” 2 degrees and have a long way to go to keep 1.5 degrees within reach (which the best available science tells us is increasingly necessary and urgent).

Despite this encouraging high-level agreement on success to date and the necessity and urgency of accelerated climate action, parties differ significantly on some of the potential outcomes and messaging from the first global stocktake. I highlight several key points here:

- There is significant disagreement along the traditional fault lines of developed and developing countries with regard to the preamble of the agreement. Developed countries favor a short version that does not make significant references to the UNFCCC convention or the Paris Agreement. Developing countries favor a more extensive preamble that recalls the foundational norms of the regime, most notably the concept of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capacities (CBDRRC). This concept recognizes the importance of a differentiated approach based on a country’s level of development. These parties also advocate references to Paris articles focused on the obligation of developed countries to provide financial and technical assistance to those with high levels of need and low levels of capacity to respond to climate change.

- In a related point—with regard to equity as a cross-cutting element of the global stocktake—there is significant disagreement about how to operationalize the concept. Most developed country parties frame equity in terms of a universal action to ensure that we can collectively limit warming to 1.5 degrees celsius. From their point of view, only this action can ensure that we avoid the unequal impacts of a rapidly changing climate and its worst consequences. Most developing countries speak about equity in terms of the need for poverty alleviation and sustainable development. From their perspective equity requires that developing nations are allocated a fair share of the remaining carbon budget in the interest of sustainable development. This would require developed countries to reduce their emissions faster than those still in need of development.

- This leads me to one of the more interesting and contentious discussions of the global stocktake. Many parties (both developed and developing) advocate including specific energy sector targets and collective commitments to “phase out” or “phase down” fossil fuel use, and/or to eliminate fossil fuel subsidies— in the interest of keeping the 1.5 degrees of warming within reach (which the IPCC tells us is increasingly urgent). Other nations, including several rapidly developing oil producing nations, note that the Paris Agreement does not give a mandate to the GST to make policy prescriptions. They argue that there are many pathways to carbon neutrality and advocate for national sovereignty in developing their nationally determined contributions (NDCs). These countries (and many developing nation negotiating blocs) argue that affluent nations who developed with the assistance of cheap fossil fuels have an obligation to peak their emissions (and fossil fuel use) sooner than developing nations— given their historical contributions to current temperature gain and to ensure that a fair share of the remaining carbon budget is available for countries in need of sustainable development. Without these reservations and the right to development, developing countries argue that global inequalities linked to colonial extraction and a history of exploitation might be permanently locked into the global economic system.

There are certainly more sticking points and I’ll provide updates on the status of the GST outcomes as negotiations continue through the weekend.

Hoping for Hope

Ashley Brown

Dec. 2, 2023

The irony of flying across the globe to only watch the opening statements on a laptop is not lost on me. Instead of what I’d hoped for, most of my day was spent lying down in the dark, hoping to relieve some pressure from my head (to little avail).

An alarm set for 2:00 pm blaring the song “Hey Look Ma I Made It” got me out of bed to watch the opening statements. With the laptop perched on the coffee table, we sat and listened to the former COP27 president welcome the current COP28 president. It may have been due to cough medicine, or the fact that I wasn’t experiencing it firsthand, or a combination of the two, but much of it felt underwhelming. With something as dire as climate change, loss and damages, and questions of justice on the line, quoting Yoda felt like a joke—a bad one. “Do or do not, there is no try” echoed through the speakers, an attempt at motivating delegates. I just sat there and stared at the screen, wondering who would actually find that inspiring beyond the occasional Star Wars fanatic.

The Loss and Damages fund—or as a group chat member called it, the “lost and damaged” fund—finally began its course on the first day of the conference. Many had high hopes for it, believing it could promote equity amongst states and hopefully allow those most impacted by climate change to repair what has been harmed. However, it became clear today that it will fall short of its goals. The United States pledged mere cents compared to what it is capable of, with some calling it “a paltry $17.5 million.” The UAE and Germany each pledged $100 million, the European Union pledged £125 million, the United Kingdom pledged €60 million, and Japan pledged $10 million. The biggest economy in the world couldn’t scrape up more money than one that’s a quarter of its size; it’s almost laughable. Loss and damages needs around $400 billion to function, yet it is currently dealing in the millions. Viewing this from the couch made me feel more ill than I already was.

I hope that the rest of COP28 proves to be more successful than the opening, going out with a bang of substantial commitment, in contrast to the stylistic an performative overtones of the opening. It would be an understatement to say that a lot goes on at COP: 70,000+ people coming from around the world, negotiations, networking, research, and meeting new friends (there’s a chance we’ve recruited a SPIA applicant). This coming together is supposed to provide more than words on paper and new connections on LinkedIn; it’s supposed to give us hope and promise for a better tomorrow. As far as the first day goes, the hope department’s a little lacking. It is easy to fall down the climate change rabbit hole of doom and gloom; hope is necessary to keep going, it’s critical to avoid nihilism.

I have hope in the fact that we were able to create the L & D fund, and that we have some money in the bank. It’s unprecedented, and most certainly a win- we must celebrate these when we can. On the other hand, I have little hope in how this fund will be operationalized; there is so much work to be done in terms of accessibility, civil society, contributions, and more. But if there’s one thing to take away, it’s that hope and despair are not dichotomies or binaries. It’s a spectrum we’re always sliding on, possibly even at two places at the same time. There is no hope or despair, but hope and despair.

An Overall Rocky Start to COP28

Charity Zimmerman

Graduate Student School of Policy and International Affairs and School of Economics,

NSF One Health and the Environment Research Trainee

As I start to write this, I’m sitting on a bus on my way to Boston Logan airport, where I will board my flight to Dubai to attend COP28. As a first-time observer, I’m still feeling confused, overwhelmed, and likely unprepared for what is to come. To help myself get into the right headspace, I’m listening to an audiobook titled Inconspicuous Consumption, by Tatiana Schlossberg, thinking about all the compounding factors that have led us to the climate crisis we face today.

Despite feeling infinitely grateful for the opportunity to attend a COP and possibly brush elbows with heads of state and important climate activists, I find myself contemplating the hypocrisy of loading myself onto a Boeing 777 to go and talk about emissions reductions. The more immersed I become in the world of climate and environmental activism and governance, the more guilt I feel about many of the choices I make each day. Even in this moment, I’m reflecting on the fact that my laptop was likely charged by non-renewable sources of energy, adding to my own ever-growing carbon tab. While I think it is important for each of us to do our best to avoid unnecessary consumption (e.g., minimize the unnecessary stocking-stuffers this year), I find myself hoping for some serious systemic progress at COP28. Although I still personally harbor a bit of climate guilt, I know that the work that will happen at COP28 is important. From our universal Covid-19 experiences with long-winded zoom meetings, I think it’s safe to say that in-person dialogue is an important facet of creating best-case outcomes and ensuring that all voices are heard.

In disappointing news, we’ve had some bumps in the road leading up to this year’s COP: President Biden will not attend the conference this year and documents have been leaked suggesting that the COP28 President (who is an executive for the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company) was planning to use the conference as an opportunity to advance oil and gas deals. This is extremely disheartening. Climate justice is a key issue for this year’s conference, and despite knowing that this year’s president is an oil executive, I had been holding onto the idea that involving major players in high level roles might help advance the overall movement towards maintaining the 1.5 Celsius goal. If one of the major action points of this COP is to encourage stakeholders to triple renewable energy capacity, this doesn’t feel like a successful start to the conference, but I have to remain optimistic. While COP primarily serves as a platform for diplomatic climate negation, it is also important for our leaders attending (or not) and facilitating the COP to remember that public perceptions matter.

In disappointing news, we’ve had some bumps in the road leading up to this year’s COP: President Biden will not attend the conference this year and documents have been leaked suggesting that the COP28 President (who is an executive for the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company) was planning to use the conference as an opportunity to advance oil and gas deals. This is extremely disheartening. Climate justice is a key issue for this year’s conference, and despite knowing that this year’s president is an oil executive, I had been holding onto the idea that involving major players in high level roles might help advance the overall movement towards maintaining the 1.5 Celsius goal. If one of the major action points of this COP is to encourage stakeholders to triple renewable energy capacity, this doesn’t feel like a successful start to the conference, but I have to remain optimistic. While COP primarily serves as a platform for diplomatic climate negation, it is also important for our leaders attending (or not) and facilitating the COP to remember that public perceptions matter.

In an unlucky turn of events, two days before the opening ceremony, one of my fellow UMaine observers and I developed low-grade fevers and had to miss the first day of the COP as we await negative Covid test results. We are on the up-and-up and hopeful to join in for the rest of week one, but in the meantime, we will be closely following the events at COP and hoping that despite some negative publicity about the conference, we will see a net positive outcome.

A Front Row Seat to the Climate Negotiations!

By Cindy Isenhour

Welcome to the University of Maine COP28 Blog!

Please follow along for first-hand and real-time insights into the climate negotiations taking place in Dubai, November 30th – December 12th, 2023.

Over the next two weeks, members of our delegation will be following key negotiation streams including discussions linked to fossil fuel “phase down” or “phase out”, the outcomes of the first Global Stocktake, as well as how the international community might finance the new loss and damage fund.

Please keep an eye out for new posts each day!

The University of Maine and Maine Law delegates attend the negotiations to: 1) learn more about international climate governance; 2) conduct research related to the negotiations; and occasionally 3) to contribute to the process through speaking engagements based on expertise.

This year’s delegation includes three faculty and five graduate students, each with unique interests and perspectives on the process. They include:

- Dr. Cindy Isenhour – Professor of Anthropology and Climate Change, University of Maine. FOCUS: how to equitably allocate the remaining carbon budget among parties in the interest of the right to development.

- Dr. NIck Micinsky – Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Affairs, University of Maine. FOCUS: climate migration and adaptation policy, particularly in the African Group of Nations.

- Dr. Anthony Moffa – Associate Professor of Environmental Law, University of Maine School of Law. FOCUS: non-party stakeholder participation, loss and damage, torte law and climate litigation.

- Charity Zimmerman – Graduate Student, School of Policy & International Affairs/Economics. FOCUS: climate adaptation finance, agriculture and water.

- Ashley Brown – Graduate Student, School of Policy and International Affairs. FOCUS: least developed countries negotiation strategies, climate justice, equity.

- Natalie Nowatzke – JD Candidate, Maine Law. FOCUS: loss and damage, the arctic, global stocktake.

- Bryant Wolff – Law Student, Maine Law. FOCUS: loss and damage, long-term climate finance, global stocktake.

- Geetanjali Talpade – Law Student, Maine Law. FOCUS: woman and gender constituency, the gender platform, mitigation.

Funding Acknowledgement: The UMaine/Maine Law delegation to COP28 extends our sincere gratitude to the University of Maine Climate Change Institute, the Dan and Betty Churchill Exploration Fund, The School of Policy and International Affairs, and Maine Law for their support of this important educational and research opportunity.

We look forward to sharing our experiences and perspectives with you!