COP 27

Human Rights and COP27

Nicholas Micinski is Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Affairs at the University of Maine.

Most people at COP27 recognize climate change as the most pressing issue of our times. It is an existential threat to our communities, economies, and political institutions. Climate change also threatens our individual lives and security. One framing of this is through human rights and human security.

Fifty of the UN’s official independent experts—including the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights in the context of climate change and the Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment—made a statement calling on states at COP27 to make human rights central to the climate negotiations. The statement highlights the different ways that climate change impacts human rights and human rights impacts the climate. However, they had several specific asks, including to “include human rights considerations in their nationally determined contributions and other planning processes and ensure that market-based mechanisms have effective means for protecting human rights and effective compliance and redress mechanisms, including mandatory environmental and human rights due diligence laws and policies.” The nationally determined contributions (NDCs) are a critical part of the 2015 Paris Agreement’s Global Stocktake, which requires states to make specific pledges toward reducing their emissions. Including human rights in the NDCs is a crucial way to ensure the energy transition is both just and rights-base.

UN Special Rapporteur Tendayi Achiume also highlighted the role of racial justice at COP27. Because climate change hurts certain people and areas more than others, there have emerged “global ‘sacrifice zones’—regions rendered dangerous and even uninhabitable due to environmental degradation… more accurately described as ‘racial sacrifice zones.’ Racial sacrifice zones include the ancestral lands of indigenous peoples, territories of the Small Island Developing States (SIDS), racially segregated neighborhoods in the Global North, and occupied territories facing drought and environmental devastation. The primary beneficiaries of these racial sacrifice zones are transnational corporations that funnel wealth, towards the Global North, and privileged national and local elites globally.” As such, the UN climate negotiations need to address the “racist colonial foundations of the ecological crisis.” In some ways, making Loss and Damage a priority at COP27 was an attempt to address the historical global (economic and racial) inequality in emissions between the Global North and Global South.

There were many other entry points for human rights at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheik. For example, there was the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Pavilion hosted by UN DESA, which hosted events on financing SDG7 on affordable and clean energy; SDG6 on clean water and sanitation; and SDG13 on “urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.”

I attended a side event on “Advancing rights-based protection of climate migrants–what role for local and international actors?” The guest speakers discussed how climate change is pushing people to move and how human rights frameworks should be applied. One key takeaway is that human rights apply in all situations and are not contingent on migration status or the type of climate disaster. Despite the potential, there are few legal routes to justice leaving most support for climate migrants as voluntary and aid based, instead of human rights based.

Despite the somewhat disappointing outcome of COP27—with unresolved questions around Loss and Damage and real commitments to reducing emissions—there are increasing spaces for discussion and inclusion of human rights within the global climate agenda.

Consensus Means Equitable But Slow

Mikala Bolmer, University of Maine School of Law – J.D. Candidate, Class of 2023

COP negotiations go slowly. They feel like they’re going slowly when you’ve been listening to the same delegate talk about the same three talking points for 15 minutes, and they feel like they’re going slowly when there’s nothing even close to a draft text after dozens of

hours of negotiations, and they feel like they’re going slowly when you read the final decision papers each year in light of the monumental climate crisis. Why?

Why can’t we make more “forward progress” faster? Anyone who has tried to get 4 or more people to agree on which board game to play, or what TV show to watch, or, heaven forbid, where to go to dinner understands why. Sometimes no one has an opinion; sometimes everyone has very strong opinions, but those opinions don’t align at all; and sometimes, perhaps worse still, everyone has partial opinions that meticulously rule out every apparent option until there is nothing that everyone is happy with, so you just play Monopoly, (the worst game. Don’t @ me.) or you watch whatever is already on the TV, or you go to the same, tired Olive Garden for dinner that you always go to. Consensus approach.

Folks frequently critique COPs for generating agreements that barely move the needle, despite the rapidly approaching climate apocalypse. After a week in Sharm el-Sheikh, I believe it can be attributed to the use of the consensus approach for decision making. Consensus Approach is a way of reaching agreements that requires every Party to agree. Not just a simple majority (more than half). A super majority (two-thirds) also won’t do, and not even all but one will work. No. It must be every Party who engages in the negotiations. Recall the “four people trying to decide where to have dinner” example, and then scale that up to 198 Parties trying to solve the largest, wicked-est problem of our geologic era.

It’s rough.

But it’s also completely necessary. International interactions must be by voluntary agreement. Parties can declare that “all countries must reduce carbon dioxide emissions,” for example, but what happens when one or several countries reduce some of their emissions but not to the full extent agreed upon? Do we ignore it and effectively nullify the agreements? Should we just blow up their highest-emitting factories, forcing compliance? Do we make the decision as an individual country to sanction that country despite no such allowances in the agreements? Are we even allowed to make those decisions? And what if then, in the eyes of another country, we fail to comply with a different provision of the agreement? Are we now open to sanctions ourselves, and are we ok with that? Are we ok with individual countries making those decisions? International governance and relations are complicated, and the risk of driving others away from the table is real! And not every individual country has the power to make those decisions, so if one of those decisions is made, there are sure to be inequitable outcomes as a result.

I believe that the important attribute of the consensus approach is the inclusivity. I am not aware of another system that is as egalitarian, where the tiniest nation can sit at a table with all the other world powers, and say “No. That is not acceptable to me.” And actually be heard. Indeed, we are in this climate crisis precisely because powerful governments capitalized on their power to the detriment of less powerful governments, without listening to or respecting them. Therefore, including as many Parties as are willing to join in the conversation is essential for an ethical energy/environment/climate future.

And so we talk. And we talk, and we talk, and we talk, and we try to leverage the small amount of power that we have over each other without driving each other away, and we re-acknowledge misstatements of the best available science because correct statements “aren’t acceptable” to the powerful industries of oil-producing countries, and we reaffirm underachieving commitments that will take us well beyond 1.5°C because the US isn’t willing to pony up if China isn’t willing to renounce its designation as a developing country which qualifies it to receive loss & damage funds, and we smile for the pictures at the closing plenary session, hailing a “successful implementation COP” because it’s all better than nothing.

Helpful resource: Dealing with Consensus at UN Climate Talks

Nature is the Solution!?!

Adam Daigneault, EL Gidding Associate Professor of Forest Policy and Economics, University of Maine School of Forest Resources

Day 10 at COP27 was Biodiversity Day, where Ministers, delegates, and observers all championed the role that nature has in helping achieve global climate change adaptation and mitigation goals. Many noted that for many years the climate crisis and the biodiversity crisis have been treated as separate issues, while there really is no viable route to limiting global warming to 1.5°C without urgently protecting and restoring nature.

Day 10 at COP27 was Biodiversity Day, where Ministers, delegates, and observers all championed the role that nature has in helping achieve global climate change adaptation and mitigation goals. Many noted that for many years the climate crisis and the biodiversity crisis have been treated as separate issues, while there really is no viable route to limiting global warming to 1.5°C without urgently protecting and restoring nature.

While the topic of the day is interesting in itself (especially for a natural resources researcher like me) Biodiversity Day was primarily scheduled to help set the scene for next month’s 15th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD COP 15), which will take place much closer to home, in Montreal. Some are calling for CBD COP 15 to be a “Paris moment” for biodiversity, with key aims of the meeting to agree on a new set of goals to guide global actions through 2030 to protect and restore nature, represented in the 30×30 goal.

Here in Sharm el Sheikh, there’s a lot of buzz around using Nature-based “Solutions” (NbS) to help solve the climate crisis. And it’s hard to dispute why they shouldn’t be part of the suite of interventions that should be taken, with all the co-benefits that sustainably managing the world’s natural and working lands can provide beyond helping countries meet their climate mitigation targets. For example, while natural ecosystems play an important role in regulating climate via sequestering and storing carbon, the loss of forests, draining of wetlands, and other environmental degradation has contributed significantly to climate change. As such, most of the events I attended today focused on advancing efforts to reduce deforestation and forest degradation and restore ecosystems across the globe.

Here in Sharm el Sheikh, there’s a lot of buzz around using Nature-based “Solutions” (NbS) to help solve the climate crisis. And it’s hard to dispute why they shouldn’t be part of the suite of interventions that should be taken, with all the co-benefits that sustainably managing the world’s natural and working lands can provide beyond helping countries meet their climate mitigation targets. For example, while natural ecosystems play an important role in regulating climate via sequestering and storing carbon, the loss of forests, draining of wetlands, and other environmental degradation has contributed significantly to climate change. As such, most of the events I attended today focused on advancing efforts to reduce deforestation and forest degradation and restore ecosystems across the globe.

While it is hard to dispute the role that better managing our ecosystems can have multiple benefits on environmental, economic, and social well-being, it is also important to note that NbS are only a part of the overall suite of actions that we must take to reduce the impacts of climate change. Recent analysis that highlights that wide-scale efforts to protect, manage and restore ecosystems and land for the future can reduce peak global temperatures by 0.1 to 0.3 degrees C. Implementing NbS on its own will not enough to achieve the 1.5 degree C target, but it can definitely play an important role in mitigation, especially in the short- to medium-term.

Some studies estimate that up to 30% of total mitigation between now and 2030 could come from NbS. However, achieving this level of mitigation – even if it’s typically more cost-effective than many technology-based options – will not be easy. A recent report on the “Land Gap” estimated that countries’ climate pledges rely on more than 1.1 billion acres of land for carbon removals by 2030, and another 1.4 billion acres by 2050. For context, this is slightly more than the total area of the US.

The emphasis on preserving nature and enhancing biodiversity in the climate context is important to Maine too. Faculty and students at UMaine have created their own Maine Natural Climate Solutions Initiative, with an emphasis on identifying cost-effective opportunities to use our forests and farms to help achieve the state’s goal of being “carbon neutral” by 2045. We estimated that Maine’s forests and wood products currently remove and store more than 75% of the annual GHG emissions, and the Governor’s Forest Carbon Task Force recommended that we set a goal to maintain the current sequestration rate, as doing so should lead to achieving the target well before 2045. Further, several of the Maine Won’t Wait 4-year Climate Action Plan’s strategies call on the protection of the state’s natural and working lands to help meet broad climate objectives.

Biodiversity Day concluded with an enthusiastic speech by Brazil’s president-elect Lula, who arrived at COP via a private jet and was treated like a rock star everywhere he went (the chants of “Lula…Lula…” by adoring fans helped signal where he was on the grounds at any given time). “I’m here today to say that Brazil is ready to come back,” he said, pledging to get the country on track to protecting the Amazon and significantly reducing deforestation. The throngs of people, myself included, who crowded into the standing-room only overflow venue to hear his speech (in Portuguese after the chants of “No Translation” reverberated throughout the room) felt a strong feeling of optimism that nature is and will continue to be a key ‘solution’ to the climate crisis.

Climate migration on the sidelines of COP 27

This year at COP27 I’ve been following discussions about climate migration in Sharm el-Sheik. Climate migration—sometimes called climate-induced migration, climate displacement, environmental migration, or climate refugees—is when someone is forced to move because of an extreme climate event. There have been long legal debates about if climate migrants are covered by the 1951 Refugee Convention (usually not) or if they fit within disaster and humanitarian governance frameworks. The topic has been discussed in the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction and the Platform on Disaster Displacement in order to develop best practices and policy recommendations for addressing climate displacement.

While migration has not yet been central to the UN climate negotiations, climate-induced displacement was mentioned in ad hoc ways in the 2010 Cancun agreement, the 2013 Warsaw Mechanism, and the 2015 Paris Agreement. The biggest innovation came when the Paris Agreement established the Taskforce on Displacement as an institutionalized space to collect data, best practices, and recommendations.

More progress was made within the global migration regime with the 2018 Global Compact on Migration, which was the first international agreement on migration to include climate migration. The Global Compact recognizes climate change as both a slow-onset (drought, sea level rise, desertification) and sudden-onset (hurricanes, floods, environmental degradation). The agreement pushes to address climate migration through adaptation and development aid in countries of origin, rather than rights-approaches or humanitarian aid in host countries.

Despite growing acknowledgement that climate change has impacted human mobility, there was little movement on climate migration within the UN system or global governance more generally. I spent much of my time at COP27 at the Climate Mobility Pavilion, which is hosted by the Global Center for Climate Mobility and the Africa Climate Mobility Initiative. Every day the pavilion has hosted events and panels related to climate mobility covering topics like youth, women, cities, technology, and climate justice.

On 9th November 2022, the Uganda delegation hosted an event to relaunch the Kampala Ministerial Declaration on Migration, Environment and Climate Change at COP 27. Originally, signed in July 2022 in Kampala, Uganda, the Declaration agrees to “enhanced cooperation and action” on climate change impacts on desertification, livestock, unplanned movements to cities, collection of statistics, and the lack of funding and partnerships on climate migration. The agreement was signed by Uganda, Burundi, Djibouti, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, Senegal, Egypt, Algeria, Zambia.

The relaunch of the Kampala Declaration on the sidelines of COP27 is an innovative strategy of norm entrepreneurship. Uganda and the other signatories are attempting to upload the regional declaration to the global climate agenda and show how countries can cooperate on the climate-migration nexus. Their hope is that there will be both more space and time on the formal agenda for climate migration at future COPs. They also hope that the Kampala Declaration will become a model for other countries and regions seeking to address climate migration.

African countries have long been leaders in protecting climate migrants. For example, the 2006 Great Lakes Protocol on the Protection and Assistance to Internally Displaced Persons and the 2009 AU Convention for the Protection and Assistance of Internally Displaced Persons in Africa both include a broad definition of drivers of displacement that includes climate or weather-related events. Importantly, both the 2006 Protocol and the 2009 Convention are legally binding. At the UN level, states have struggled to reach agreement—let alone binding legal tools—on protecting climate migrants.

While the Kampala Declaration is short on details, it is an attempt at sparking more robust action by states in Africa and at COP that could lead to better protection for those displaced by climate change.

Making peace with COP27 in ‘the City of Peace’

Julia Hiltonsmith, PhD Student in Anthropology and Environmental Policy

Sharm El-Sheikh is often referred to as ‘the City of Peace,’ and as a woman who has heard frequent remarks regarding safety concerns in Egypt, I believe Sharm’s nickname is well-deserved. The city and its locals have been nothing but welcoming. In fact, the only conflict I felt during this trip has been an internal one.

My last blog post highlighted the discrepancies that arise from high-level climate negotiations. Snafus that arise (such as referring to the wrong text and wasting precious negotiating time) are not to be overlooked. When the stakes are so high, these hiccups can be disheartening. I often found myself wondering how the necessary substantive changes will ever take place when negotiations come to a screeching stop over single clauses or even single words.

This is not to say that the interventions made by negotiators aren’t justified. As the G77 negotiator rightly argued, it is only fair that Developed Countries scale up their financial support for the National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) prepared by Developing and Least Developed Countries. After all, it is a condition of the Paris Agreement that they should do so. Despite this, getting Developed Country negotiators to agree to language that corroborates this obligation has proven to be tricky. In fact, this point of contention caused a stalemate during the last NAPs consultation that I attended during Week 1 of COP27.

Apart from the negotiations impasses, there were other causes for concern at the COP. One might consider all the emissions that resulted from over 30,000 people flying in to attend the conference. The University of Maine delegation prioritized offsetting these carbon emissions, but the same may not be said for the rest of the attendees. One may also consider Egypt’s laws against protests, which have traditionally been an integral part of COPs in years past. It’s difficult to blame protestors for their civil disobedience, especially when more than 600 fossil fuel lobbyists were in attendance this year. Most importantly, one cannot overlook Egypt’s human rights abuses, as well as its silencing and imprisonment of environmental rights activists.

Clearly, there are many qualms to be had with these high-level negotiations. Being an anthropology student requires me to view these processes through a critical lens. Without such a perspective, one might argue that important action items such as Loss and Damage or Adaptation Finance may never have made it on the agenda. However, this critical lens has not indicated that high-level negotiations and their outcomes deserve dismissal. We cannot throw the proverbial baby out with the bath water.

When I consider where climate concerns started and how quickly actions have developed, I feel a sense of hope that the urgency of the matter is taken seriously by society at large:

While negotiations come to a halt because of language and verbiage, negotiators from hundreds of different countries demonstrate a level of appreciation and trust towards their colleagues in their responses to interventions.

While nations work together to formulate appropriate adaptation responses, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and civil society network and band together to formulate plans for effective change on the ground.

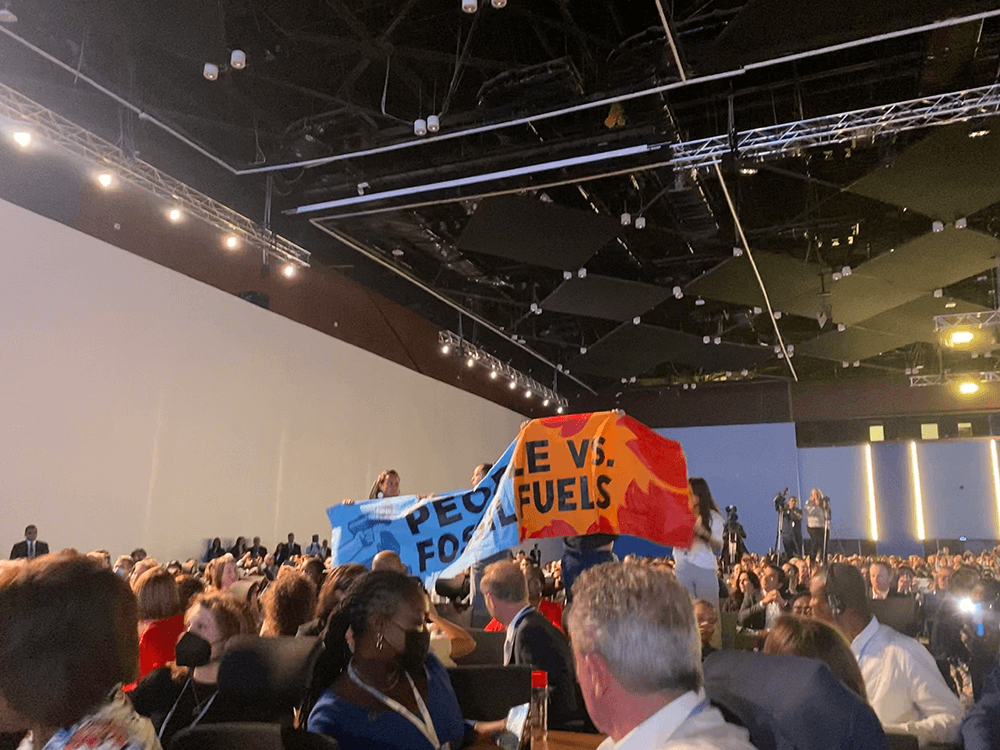

While the fossil fuel industry is working overtime to maintain their stronghold, many COP attendees made it clear that they will fight their way out of those grips. What’s more, during President Biden’s address, young Indigenous activists startled the crowd awake with a war cry and held a banner proclaiming “People vs Fossil Fuels.”

While Egypt is actively holding activists prisoner, our US representatives are having difficult conversations with the host country’s government about the human rights abuses and imprisonment of environmental activists.

While COPs may seem to be promoting greenwashing and backsliding from uncommitted countries, the conference offers a platform for civil society and stakeholders to express their grievances over some nations’ lack of ambitions.

Ultimately, while COPs may offer one solution to collaboratively fighting the climate crisis, they cannot do so independently. Rather, these negotiations rely on the participation of local and grassroots organizations. That is, the participatory processes that shape the COP cannot take place without the influence of individuals. During the opening plenaries, Prime Minister Motley of Barbados advocated that we “hold [leaders] accountable and ask [them] to act in [our] name[s] and ask [them] to save this earth and the peoples of this earth.” It is apparent that our presence and participation in these high-level negotiations is integral to advancing mitigation and ensuring equity is achieved in the process.

There is no universal solution to the climate crisis. Instead, we must recognize how multi-level cooperation works in unison to achieve our unifying goal: to prevent global warming to 1.5°C and to ensure equitable participation and outcomes for all.

Lost and Damaged

Dr. Anthony Moffa, Associate Professor Maine Law

As a law professor who teaches both torts and environmental law, the building momentum on loss and damage negotiations from week one of COP27 had captured much of my attention by the time of wheels down in Sharm El-Sheikh. As both Cindy and Tori noted in their posts bookending the first week, developing nations — especially those in Africa, small island states (AOSIS), and the G77 (the largest intergovernmental organization of developing countries in the United Nations) – have been advocating for a dedicated source of compensation for the losses they are already experiencing from climate change.

Loss and damage is like an international-scale climate tort. Domestically, tort law allows you to seek a civil remedy ($$$) in court from someone who has wronged you. Perhaps the most familiar subspecies of tort is personal injury. Torts does much more than protect your right to be free from bodily harm, though. In the climate context, you may have read about the cities and states suing fossil fuel companies in United States courts in attempt to hold them responsible for the real costs of climate change. Those are primarily torts claims. Compensation for Loss and Damage has its roots in the same “polluter pays” principle. Communities, even at the nation state scale, currently feel the pain of climate change in human health and dollars and cents. Many of the most harmed nations have also historically contributed the least greenhouse gases to our atmosphere.

Being a law professor, I took a different approach to our week one delegation, focusing my attention acutely on the negotiation sessions and the technical text debated by the parties from the first day. I am hoping my perspective over the course of the week can add to the stories you read about during week one of COP27. Perhaps the most crucial question will be whether the parties can agree to launch a financial mechanism right away or will instead agree to just continue the process with an eye towards 2024 (COP29) for a firm commitment.

Week two negotiations began with a late afternoon document drop from the facilitators. They circulated an “elements paper” to the parties just a couple of hours before a negotiating session on the financing mechanism. The paper purported to capture the discussions of the prior week and reflect options for potential agreement. When the parties met, almost every country used the first of their five minutes of floor time to complain about the lateness of the draft they were meant to be discussing. Despite these claims of inability to fully digest the document, a substantive rift emerged. Some parties clearly wanted to leave Sharm El-Sheikh with a functioning finance mechanism in place. Others (notably including the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom) clearly preferred to agree only on the “process” and essentially punt the details to 2024. The draft document made no party happy on this particular point. The facilitators listed element 5 as “[a]greement of the ‘process’ to be launched at COP 27,” raising the hackles of the small island states, developing countries, and some African nations. Later in the document one option included “a new operating entity of the Financial Mechanism . . . responding to loss and damage,” which the United States seemed to dislike. All agreed that they needed more time to review the document. The facilitators offered to hold another session later that night. The G77, however, wanted to submit their own draft document to the facilitators to incorporate before negotiations resumed. Through a series of maneuvers their negotiator skillfully blocked any further official negotiations on day one. As the night dragged on, back at our accommodations, we received notification of parties submitting their own points on the matter, all seeming to anticipate heated negotiations over the rest of the week. I, for one, will be watching and reporting back to you here.

Dialogues between Indigenous Peoples, Local Communities and Parties

Gabrielle Hillyer, PhD Candidate – Ecology and Environmental Sciences

Over the last few days at COP27, several facilitated working groups, committees, and delegations have met to discuss their opinions and critiques of the ongoing negotiations. As stated previously, I have been following the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform (LCIPP), including their facilitated working group. This included attending and observing two dialogues, namely, the LCIPP Multistakeholder dialogue and the LCIPP Annual Gathering of Knowledge Holders Part II, Dialogue with Parties.

The LCIPP Multi-stakeholder dialogue creates space for conversations between Indigenous peoples, local communities, and other NGOs about climate action. It follows a structured agenda starting with a brief opening invocation, usually including an Elder sharing a story or song in their native language. I was able to listen to Chief Vyacheslav Shadrin, a Chair of the Council of Yukaghir Elders from the area known as Russia. He shared a story from his community, geared towards identifying everyone in the audience as brothers, sisters, or members of the same family under the Sun Mother and Creator. Afterwards, members of the facilitated working group, a subset of elected leaders who represent the LCIPP in other negotiations, gave short presentations on the topic, “the importance of participation of Indigenous peoples and local communities in the design and implementation of climate policy.” These presentations reiterated many themes, including the importance of collaboration, the value of Indigenous youth in knowledge seeking, sharing, and climate action, and that Indigenous peoples’ voices are often nature’s voices because of their cultural values.

The LCIPP Multi-stakeholder dialogue creates space for conversations between Indigenous peoples, local communities, and other NGOs about climate action. It follows a structured agenda starting with a brief opening invocation, usually including an Elder sharing a story or song in their native language. I was able to listen to Chief Vyacheslav Shadrin, a Chair of the Council of Yukaghir Elders from the area known as Russia. He shared a story from his community, geared towards identifying everyone in the audience as brothers, sisters, or members of the same family under the Sun Mother and Creator. Afterwards, members of the facilitated working group, a subset of elected leaders who represent the LCIPP in other negotiations, gave short presentations on the topic, “the importance of participation of Indigenous peoples and local communities in the design and implementation of climate policy.” These presentations reiterated many themes, including the importance of collaboration, the value of Indigenous youth in knowledge seeking, sharing, and climate action, and that Indigenous peoples’ voices are often nature’s voices because of their cultural values.

Two panels followed, the first focused on strengthening participation of Indigenous peoples and local communities in the design of climate policies, and the second focused on equitable treatment of Indigenous and local knowledge in a climate action space. Both panels highlighted that science can often limit the actions, expressions, visions, and crises that are faced by indigenous people. What causes these limitations? Elders and other community members stated it was a lack of inclusivity during the development, implementation, and writing during research projects. One of the Indigenous audience members highlighted that scientists should not “write about us, without us.” Similarly, other audience members reiterated that science doesn’t take accountability for the structures that limit Indigenous people’s ability to practice, where non-Indigenous scientists and policy makers “have looked down,” or cultivated years of “opposition” to Indigenous practices, which impacts the ability for Indigenous Elders, youth, scientists, and others to collaborate with non-Indigenous people from a place of solidarity. This place of solidarity was identified often as the only space from which truly equitable and effective climate policy could develop.

Additionally, I was able to attend the LCIPP Annual Gathering of Knowledge Holders Part II. The LCIPP Annual Gathering of Knowledge Holders is a series of meetings where knowledge holders, Indigenous youth, community members, and others share their technologies, efforts, and actions related to responding to climate change. The goal of these meetings is creating a space for learning, sharing, and participation across the seven UN socio-cultural regions, and inform climate policy. The second part of the meeting is more tailored to sharing recommendations from Indigenous communities and local communities with party members and asking parties questions about how they are integrating these findings in their negotiations. During this dialogue I was able to hear how different parties addressed the question, “How can Parties and constituted bodies integrate the outcomes from the roundtables in their deliberations, UNFCCC processes and framing the national climate policy?”. Party representatives from Canada, Bolivia, Finland, Norway, Columbia, and others each spoke, highlighting their process of incorporating Indigenous perspectives into their negotiation. This included collaborations with local Indigenous organizations such as the Sami Climate Council or having First Nation representatives in a country’s delegation.

Additionally, I was able to attend the LCIPP Annual Gathering of Knowledge Holders Part II. The LCIPP Annual Gathering of Knowledge Holders is a series of meetings where knowledge holders, Indigenous youth, community members, and others share their technologies, efforts, and actions related to responding to climate change. The goal of these meetings is creating a space for learning, sharing, and participation across the seven UN socio-cultural regions, and inform climate policy. The second part of the meeting is more tailored to sharing recommendations from Indigenous communities and local communities with party members and asking parties questions about how they are integrating these findings in their negotiations. During this dialogue I was able to hear how different parties addressed the question, “How can Parties and constituted bodies integrate the outcomes from the roundtables in their deliberations, UNFCCC processes and framing the national climate policy?”. Party representatives from Canada, Bolivia, Finland, Norway, Columbia, and others each spoke, highlighting their process of incorporating Indigenous perspectives into their negotiation. This included collaborations with local Indigenous organizations such as the Sami Climate Council or having First Nation representatives in a country’s delegation.

Both dialogues highlighted the importance of Indigenous voices and knowledge systems within the negotiations around international climate policy. One panel member raised the point that “unless you address colonization, you are just putting a bandaid on the wound,” referring to climate change. These dialogues serve as one of the many spaces cultivated to address issues stemming from colonization which caused climate change in the first place, shifting conversations out of closed meetings into large plenary halls with plenty of seats.

Energized by US Dignitaries (and Coffee)

Mikala Bolmer, University of Maine School of Law – J.D. Candidate, Class of 2023

The UMaine COP27 Delegation for Week 2 started our second day bright and early. We were out of the AirBnB before 7:45, and on the bus north to the COP venue. We found ourselves on a bit of a prolonged hunt around the pavilions for our personal energy sources – coffee (and tea for me, which is distressingly poorly represented here!) Finally found some coffee, but by then we had veered so far off course, we lapsed into our now-tired refrains of “I think the pavilion we want is this way…” “Oh no wait! It’s this way!”

Thanks to Nick’s solid map-interpretation skills, we finally found the pavilion we were hunting – the We Mean Business Hub pavilion – to listen to the U.S. Department of Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm respond to a few questions from Amit Bando, Ceres’ Chief Economist and Senior Advisor for Just and Inclusive Economics about the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Nick had learned about this opportunity the day before through one of the dozens, if not hundreds, of email updates you can sign up for for COP-related events.

Mr. Bando began by asking about opportunities the IRA provides specifically for private sector actors, and Secretary Granholm had a laundry list of opportunities designed to benefit renewable energy transition projects in the US while centering historically overburdened and vulnerable communities. It was an energized, thirty-minute discussion wherein Secretary Granholm enumerated dozens of ways the IRA is investing in and incentivizing a just, clean energy transition. She spoke at length about centering fenceline or frontline communities with the investment money, pointing to President Biden’s Justice40 Initiative in particular.

Secretary Granholm then took a few moments to turn the conversation back on Mr. Bando, asking him for a more global perspective on centering impacted, climate-vulnerable communities in global climate investment initiatives. He acknowledged the complexity of this problem, which depends greatly on size, scale, sector, and geography of the investment communities, the investors, and the actual investment projects. Crucially, Mr. Bando highlighted that the biggest complicating factor for investment is policy because for most global climate investment projects, the finance and the technology exists, but the implementation mechanisms do not. Investors do not have reassurances that the financial infrastructure exists in the areas they want to invest to ensure that the money will go where it is intended, and project developers do not have reassurances that their projects will be faithfully implemented as designed. These barriers can and do fully derail investment, and unfortunately the places that need the most investment are the most vulnerable to this policy gap as well, (as discussed in several previous blog posts.)

Secretary Granholm reflected these concerns while discussing US global “reinvestments” and the roadblocks standing in the way. She said the US wants to make sure the vital, renewable energy technologies, such as offshore wind, solar arrays, and next generation nuclear advancements are “ubiquitous, and democratized,” and accessible around the world, to ensure the developed nations aren’t the only ones moving towards a clean energy future. It was a jam-packed thirty minutes, and then we started back towards other areas of the venue to continue our day.

Fun fact: Professor Moffa has a keen “important person” radar, so passing through the pavilions on the way to the RINGO morning meeting, Professor Moffa recognized U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry by his voice – he was giving a speech about the Adaptation Fund at the Egypt pavilion. Then Professor Moffa saw an agenda item on the US pavilion’s schedule that caught his eye, and sure enough it was Mr. Kerry again, this time to introduce the High-Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (approx. 01:50:00 – 02:43:00). Mr. Kerry gave a speech about the importance of decarbonizing the shipping industry, and then he segued into the high-level panel of energy diplomats from around the world discussing commitments and advancements to decarbonize the shipping industry.

By then it was 11am, and we had some negotiations to get to, but later Professor Moffa yet again correctly identified an event at the US pavilion about Energy EarthShots Initiatives moderated by Secretary Granholm (approx. 08:18:00 – end).

After a long day book-ended by delightful discussions with Secretary Granholm, we headed back home feeling energized.

Loss and Damage in Africa

Victoria Markiewicz, Graduate Student School of Policy and International Affairs

COP27 has been an incredible and hectic experience so far. After months of preparation for the travel and the negotiation topics, it is just sinking in that I am actually at the conference. The past few days have been a blur as I walk past thousands of people all speaking different languages and wearing traditional clothing from all over the world. We squeeze by one another to get into meeting rooms and to get in line to buy pre-made sandwiches for lunch. We sweat together in the desert sun while walking across the outdoor courtyards and we get to introduce ourselves and exchange cards as we sit beside each other at events.

While there are literally hundreds of topics being discussed at COP, I have been following the priorities of African countries – namely finance and adaptation. I am conducting interviews with African delegates I meet at the conference to advance my research on negotiation strategies and power dynamics in the UNFCCC. I am interested to explore how countries in the Global South leverage their vulnerability to meet (or not) their climate priorities. Africa is in a unique position as the entire continent only produces 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions but suffers from some of the worst effects of climate change.

I have been spending a considerable amount of time at the “Africa Pavilion” here at COP which represents the whole continent and is sponsored by the African Union. Although many individual African countries have their own pavilions, it seems the most action is at the regional pavilions. The African pavilion has a central location and is frequently packed with African presidents, negotiators, observers, and press. I was able to get a seat by showing up 30 minutes early to the risk prevention session led by the president of Mozambique.

I caught a presentation by representatives from the International Federation of Red Cross (IFRC), the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), the UN Development Program (UNDP), the president of the World Bank – David Malpass, the president of the African Union Commission – Moussa Faki, and the president of Mozambique – Filipe Nyusi. Together they presented about disaster risk prevention in Africa. They have been working on implementing the Africa Multi-hazard Early Warning and Early Action System (AMHEWAS) which is a mechanism to alert citizens about extreme weather events so that they can prepare or evacuate. Many extreme weather events are predictable but there are not currently systems to disperse the crucial information in a timely measure which costs many African lives every year. At a systemic level, disaster risk prevention also saves crucial funds for African governments by preventing emergency rescues and destruction of property during extreme weather events. These funds could be spent on adapting to climate change instead.

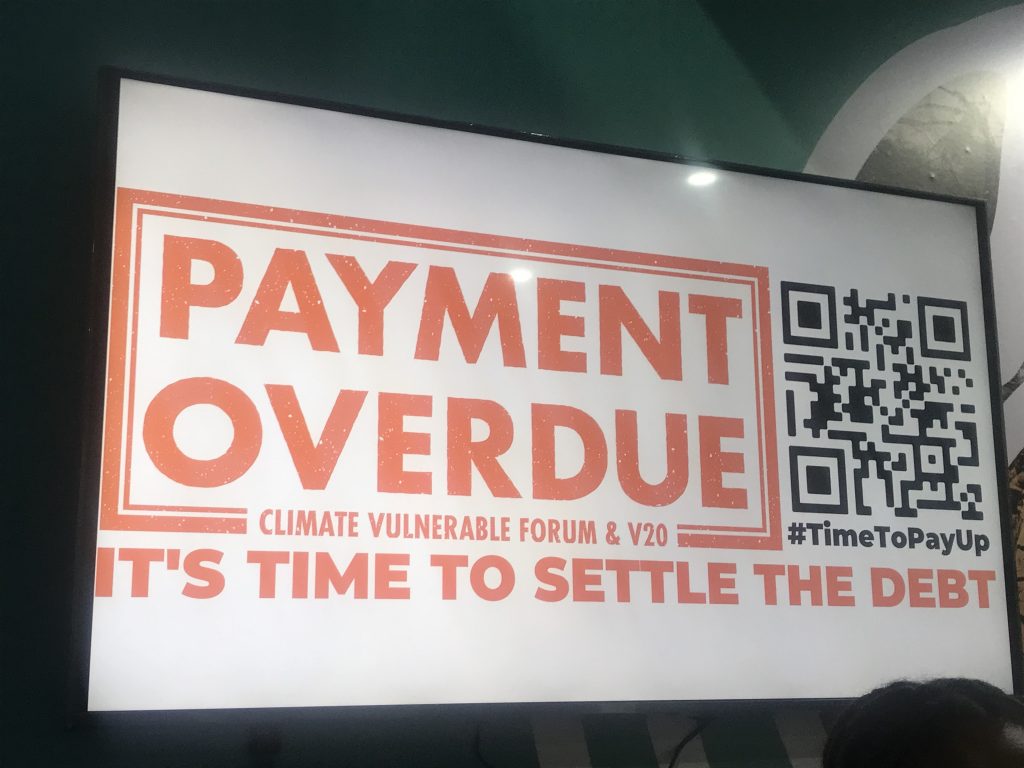

However, even if disaster risk prevention saves every African life, events such as drought, floods, cyclones, desertification, and sea level rise will still cause destruction of property and a loss of resources. The cost of repairing these damages is staggering, and climate justice advocates say the African people shouldn’t have to pay for it since they are barely contributing to climate change in the first place. That’s where “loss and damage” (described in another post) comes in. One of several mechanisms for climate finance, loss and damage is top of mind for most negotiators. It refers to climate aid from the Global North to the Global South to compensate parties for losses that cannot be adapted to or replaced.

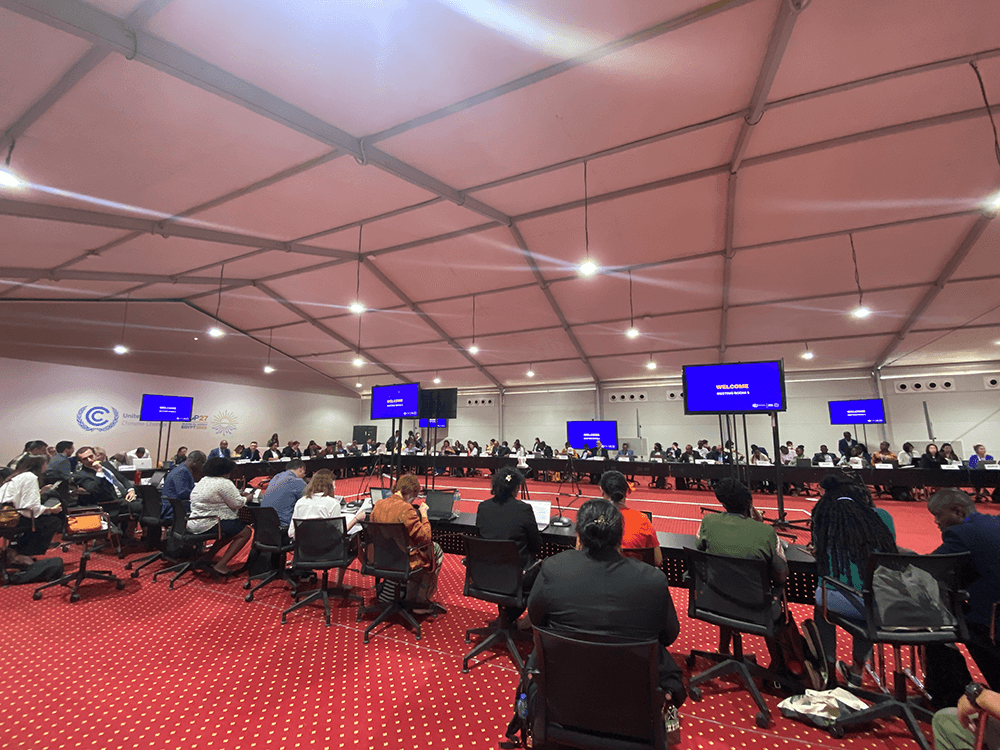

To learn more about this topic, I pushed my way into a full and stuffy meeting room past a security guard to hear an official negotiation about loss and damage finance. Negotiators from at least 100 countries sat at long desks in a giant circle with paper cards in front of them to note the country they represented. Apart from negotiators from individual countries, there was also a representatives for the negotiating blocs, such as the G77 and AOSIS. The meeting was difficult to follow because of the loud noises from the A/C and the planes flying overhead, the low quality of the microphones that made everyone’s voices sound garbled, and the lack of chairs for observers like myself. All the observers sat on the floor, trying to take notes without being able to see or hear who was speaking. It was a challenge. Mostly the discussion focused on what type of governing body would rule over the loss and damage applications, funding, and coordination. Each negotiator spoke for 1-5 minutes about their country’s feelings on a loss and damage governing body before the UNFCCC speaker moved on to the next negotiator. The discussion was very technical. I left after an hour to attend a press conference, which tends to be much more straight forward and interesting.

I attended several more meetings and sessions throughout the day but I noticed a definite theme running throughout the conference: people in the Global South (and those most vulnerable to climate change) are impatient with the eternal discussions and negotiations. They want action from the Global North (US, Australia, Canada, China) on reducing greenhouse emissions and they want financing to help their communities deal with the climate change disasters that they are already experiencing. These actions were promised by developed countries in 2015 through the Paris Climate Accords but those promises have not yet been met.

Negotiations on National Adaptation Plans Halted by Bureaucratic Snafus

Julia Hiltonsmith, PhD Student Anthropology and Environmental Policy

November 9th marked the third day of COP27. After two days to settle in, Party delegates are deep into the heart of one of their main objectives: negotiating. While there are a number of noteworthy agenda items one could follow, my own research interests in bilateral water governance and international cooperation have compelled me to monitor matters related to adaptation.

November 9th marked the third day of COP27. After two days to settle in, Party delegates are deep into the heart of one of their main objectives: negotiating. While there are a number of noteworthy agenda items one could follow, my own research interests in bilateral water governance and international cooperation have compelled me to monitor matters related to adaptation.

One such matter on adaptation relates to National Adaptation Plans (NAPs). NAPs are the main international vehicle for implementing adaptation nationally, integrating subnational and local actions, and linking to regional and global processes. The process of developing NAPs was established to enable nations belonging to the Least Developed Country (LDC) groups and other developing country Parties to identify medium- and long-term adaptation needs and to develop and implement strategies and programs to address such needs.

The primary objectives of the National Adaptation Plans are to reduce vulnerability to the impacts of climate change by building adaptive capacity and resilience and to facilitate the integration of climate change adaptation into relevant new and existing policies and actions. The United Nations supports these efforts by providing five categories of technical assistance to countries: answers to simple technical inquiries; delivery of specific data / knowledge products (i.e. datasets, analytical tools, guidance material); long-term capacity building; review of draft NAPs; and facilitation of integration of adaptation priorities into country support strategies.

As of November 9th, only 39 countries have submitted their NAPs. The UN has offered their congratulations to those countries who have already submitted their NAPs, but they are calling for many more to follow suit.

Based on the limited number of countries who have finalized their National Adaptation Plans, it is no small feat to complete this task. In several of the negotiations related to this matter, Ghana (representing the G77 countries and China) raised multiple concerns that developing countries have not received sufficient multilateral support to face the dangers of climate change. In particular, Ghana raised concerns about the lack of promised climate financing for developing countries during their first negotiation session. Many countries echoed this concern.

Certainly, climate financing for these initiatives is of great importance, especially at a COP that boasts goals for implementation — but also of great importance is the sense of clarity in communications that is required for successful negotiation efforts. Simply put, the power of clear and succinct communication cannot be understated. Every Party delegate participating in negotiations must be on the same page. But in this case, they quite literally were not.

At the end of the first meeting related to the Report of the Adaptation Committee, it came to light that participating Parties were referring to different versions of the relevant document. The meeting adjourned with agreement amongst the Parties that the Secretariat would send out the correct version to avoid future confusion. As promised, the document was sent out to Parties and observers and also posted online.

But these efforts to avoid confusion were thwarted when Parties realized that the document sent out by the Secretariat was not the one from which negotiators intended to build. After obvious tensions and a quick, informal side huddle by Parties, it was agreed that Party members would work from a particular version of the document.

After what seemed like countless minutes of this 1-hour meeting were used to send out the Parties’ requested version of the document, it became apparent that, yet again, this was not the agreed upon version. The meeting adjourned with no advancements other than an agreement on the document that would be referenced going forward.

This incident highlights the complexities of large-scale bureaucratic processes. The scale at which environmental efforts take place has a clear correlation with the time required to make tangible, impactful change. In other words, the higher the governance structure, the more time required to make progress. Although the large-scale interventions that occur at the COP are integral to the widespread change necessary to keep us at 1.5°C or below, we must not forget the grassroots efforts that are taking place both at COP and in our local communities. And as we anxiously await US election results from November 8th, let us be grateful that we are able to engage with the bureaucratic processes that enable such change.

Indigenous People & Climate Change

Gabrielle Hillyer – November 9, 2022

My research follows intersections between colonization, fisheries governance, and current management practices in the wild clam and mussel fishery in the Dawnland home of the Wabanaki people, an area now known as Maine. Recognizing the layered issues related to Indigenous sovereignty, resilience, coastal access, Indigenous and non-Indigenous livelihoods, and food sovereignty, I came to COP27 to follow the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform (LCIPP), a relatively new platform started in Paris in 2015 to “strengthen knowledge, technologies, practices and efforts of local communities and Indigenous peoples related to addressing and responding to climate change”. This platform represents Indigenous peoples and local community organizations, gathering Elders, youth, and others to exchange knowledges, advocate for enhancing the recognition of Indigenous rights, leveraging and showcasing community action, and discussing and critiquing the ongoing proceedings.

Today at COP27, after grabbing a much-needed cup of coffee, I sat in on a series of side events hosted at the Indigenous Peoples Platform Pavilion, beginning with the opening ceremony. This, in contrast to many other pavilions, included singing, dancing, instruments, ceremonial blessings, and a vast array of languages, as representatives from Indigenous communities all over the world stood up to welcome everyone in their own way. The power was breathtaking. People rushing to their meetings and negotiations nearby, often representing countries that continue to perpetuate harm towards these communities, stopped to listen. For some it was very quick, taking a photo (often bumping a few others aside to get the best view), before moving away, and others it seemed were drawn in and stood, transfixed, as leaders, Elders, and others shared in their language and their practices well-wishes for COP27. Similar moments existed throughout the day and other events, where Indigenous leaders made their voices heard, sharing out their experiences and knowledge with the audience. This audience generally comprised of other Indigenous leaders and community members, news media, other non-indigenous party members and delegates, and a few NGO (non-governmental organization) observers like myself.

Several key takeaways emerged throughout the day (often bolded and underlined in my less than legible handwriting). First, Indigenous peoples are leading the way in developing new techniques to conduct relevant and accurate scientific research within Indigenous communities. For example, the Network of Indigenous Peoples of Thailand (NIPT), has developed land use maps that show rotating agriculture spaces, considered communal spaces by Indigenous peoples, that serve as a unique tool to engage with local governments in shared decision making, as described by Mr. Sakda Saenmi. Another key takeaway is related to the $1.7 billion promised to Indigenous peoples at COP26 to respond to climate change. It is not enough. One event I was able to attend was a dialogue between UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Climate Change Ian Hayes, and the Indigenous Platform, specifically indigenous leaders who raised concerns about this issue. They highlighted that the estimated value of the ecosystem services (as put on the New York Stock Exchange) is $126 trillion, yet COP26 has stated $1.7 billion for indigenous communities, which protect over 80% of the worlds biodiversity. The mismatch is obvious and highlights the power dynamics at play between Indigenous communities and other private and public sectors. Even within the $1.7 billion it was mentioned at earlier events that only 7% is going directly to Indigenous communities. This has been mentioned by a news outlets as well. Finally, the LCIPP is extremely focused on the conversation around Loss and Damages, one that will shape how funding and other mechanisms will impact communities across the globe, particularly in the global south and Arctic. Indigenous leaders – often representing the most vulnerable communities and serving as the most outspoken environmental protectors, emphasized that Loss and Damages is critical for climate justice. They argued that COP27 should culminate in a full recognition of indigenous sovereignty while providing assistance to communities on the frontlines of climate change.

Several key takeaways emerged throughout the day (often bolded and underlined in my less than legible handwriting). First, Indigenous peoples are leading the way in developing new techniques to conduct relevant and accurate scientific research within Indigenous communities. For example, the Network of Indigenous Peoples of Thailand (NIPT), has developed land use maps that show rotating agriculture spaces, considered communal spaces by Indigenous peoples, that serve as a unique tool to engage with local governments in shared decision making, as described by Mr. Sakda Saenmi. Another key takeaway is related to the $1.7 billion promised to Indigenous peoples at COP26 to respond to climate change. It is not enough. One event I was able to attend was a dialogue between UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and Climate Change Ian Hayes, and the Indigenous Platform, specifically indigenous leaders who raised concerns about this issue. They highlighted that the estimated value of the ecosystem services (as put on the New York Stock Exchange) is $126 trillion, yet COP26 has stated $1.7 billion for indigenous communities, which protect over 80% of the worlds biodiversity. The mismatch is obvious and highlights the power dynamics at play between Indigenous communities and other private and public sectors. Even within the $1.7 billion it was mentioned at earlier events that only 7% is going directly to Indigenous communities. This has been mentioned by a news outlets as well. Finally, the LCIPP is extremely focused on the conversation around Loss and Damages, one that will shape how funding and other mechanisms will impact communities across the globe, particularly in the global south and Arctic. Indigenous leaders – often representing the most vulnerable communities and serving as the most outspoken environmental protectors, emphasized that Loss and Damages is critical for climate justice. They argued that COP27 should culminate in a full recognition of indigenous sovereignty while providing assistance to communities on the frontlines of climate change.

The Prime Ministerof Barbados, Mia Mottley stated at the Opening Ceremonies of COP27, “I ask the people of the world to hold us accountable…to save this Earth.” I believe that Indigenous peoples are holding world leaders and many others accountable, hosting critical conversations that often breakdown and illuminate consequences of major decisions. COP27 serves as a unique space where Indigenous peoples voices, songs, languages, and practices are being seen and felt by policy makers, delegates, negotiators, and other non-Indigenous peoples. Time will tell whether this will push COP27 towards further equitable action.

I will be continuing to follow these events over the next week. For more frequent updates, please follow me on twitter at @GHillyer_ for a non-indigenous perspective on these proceedings. Thank you!

Climate Adaptation and the African COP

November 8, 2022 – Cindy Isenhour

Welcome! Please join us here each day for insight into the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)’s 27th Conference of Parties (COP27) in Sharm El Sheik, Egypt (November 7 – 18, 2022). Members of the UMaine delegation to the negotiations will be taking turns posting stories, reflections, briefings, and news as world leaders and civil society gather to address the urgent challenge of global climate change.

This year’s COP has been billed as the “Adaptation COP”. For many years mitigation concerns took center stage at the negotiations. However, as climate impacts have become more apparent around the world and as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports make it increasingly clear that historical and contemporary emissions have already locked us in to additional climate change — our collective lens has increasingly turned toward the need to ensure communities around the world are able to survive and adapt to a changing climate. This certainly does not reduce the need for or the important work being done on climate mitigation, but it does direct much-needed attention to the needs and priorities of communities already suffering from climate impacts like drought, flooding, more intense tropical storms, wildfires, rising sea levels and salinization.

The location of this year’s meetings in Africa underlines the importance of adaptation efforts for developing countries and lends extra symbolic weight to the need for adequate adaptation finance. The Paris Agreement brought the world together to act on climate change but hinged on the promise that developed nations would provide finance and support for developing nations who agreed to act (despite their small or non-existent contributions to climate change). Unfortunately, as a whole, developed nations have not delivered on that promise. This year’s focus on adaptation has the potential to make real gains not only toward increased adaptation finance, but also on several other mechanisms designed to improve adaptation.

Two significant negotiation streams are drawing a lot of attention this year: Loss and Damage and the Global Goal on Adaptation. The concept of Loss and Damage is based on the reality that some nations are suffering climate impacts to which they cannot adapt—the damages are such that they result in significant losses (land, culture, place) for affected people. The world’s most vulnerable nations, many of which bear very little responsibility for climate change have long argued that financing mechanisms to address loss and damage are essential for global climate justice. For the first time finance for Loss and Damage has been placed on the agenda for these negotiations.

The second negotiation stream gaining significant attention is the Global Goal on Adaptation. While the Paris Agreement is based on a global mitigation goal, to limit climate change to 2 degrees and ideally closer to 1.5 degrees of change – there is no parallel goal for adaptation. Since the negotiations in Glasgow last year, climate diplomats have been reviewing various adaptation indicators and metrics and are expected to put forward proposals for a global goal on adaptation at these meetings.

Members of UMaine’s delegation will also be following other negotiation streams including carbon trading, efforts to take stock of global progress on mitigation and adaptation, the local and indigenous people’s platform, and streams related to water and marine resource governance. Stay tuned!

Introducing the UMaine & Maine Law COP27 Delegation

November 8, 2022 – Cindy Isenhour

Welcome! Please join us here each day for insight into what is happening at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)’s 27th Conference of Parties (COP27) in Sharm El Sheik, Egypt (November 7 – 18, 2022). Members of the UMaine and Maine Law delegation will be taking turns posting stories, reflections, briefings, and news as the global community gathers to address the urgent challenge of global climate change.

The UNFCCC Conference of Parties brings together diplomats, scientists, civil society groups, industry representatives and activists from around the world. At current count, more than 110 heads of state have joined this complex mix, signaling a commitment to make progress toward preventing and adapting to climate change.

At any given time during the conference, there are negotiation sessions, side events, demonstrations, and protests. The meetings have been described as part negotiations, part conference and part circus. Our delegates are pleased to have the opportunity to participate – to learn more about global governance, to advance our research on various aspects of climate change and, when possible, to contribute to the generation of solutions. We are also pleased to share what we learn with you – our colleagues back in Maine.

Access to the negotiations is controlled by the allocation of badges by the UNFCCC Secretariate. This year the University of Maine was allocated five badges which can be “shared” across the two weeks of the meetings. This year we have five delegates attending each week… keep an eye out for their posts!

Week One Delegation (pictured above)

Cindy Isenhour, Associate Professor of Anthropology and Climate Change – Head of Delegation Week 1

- Expertise and interests related to climate accounting, the global stocktake, market-based mechanisms, the climate impact of consumption, circular economy, and climate justice.

Nicholas Micinski, Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Affairs

- Expertise and interests related to UN Process, climate migration, humanitarian aid, loss and damage, and global governance.

Gabrielle Hillyer, PhD Candidate, Ecology and Environmental Sciences

- Expertise and interests related to indigenous sovereignty, knowledge co-production, intersections between Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement, Local and Indigenous People’s Platform (LIPP).

Julia Hiltonsmith, PhD Student, Anthropology and Environmental Policy

- Expertise and interests related to Water governance, international cooperation, climate adaptation, participatory policy formation and implementation, bureaucratic process.

Victoria Markiewicz, MA Student, School of Policy and International Affairs

- Expertise and interests related to climate adaptation, human rights, food security, and institutional norms.

Week Two Delegation:

Nicholas Micinski, Assistant Professor of Political Science and International Affairs – Head of Delegation Week 2

- Expertise and interests related to UN Process, climate migration, humanitarian aid, loss and damage, and global governance.

Mikala Bolmer, J.D. Candidate, Maine Law

- Expertise and interests related to climate obstructionism, international climate governance, policy and law for climate justice, policy equity.

Adam Daignault, E.L. Giddings Associate Professor of Forest Policy & Economics

- Expertise and interests related to economic analysis of climate policy, carbon sequestration, land-based mitigation policy.

Daniel Hayes, Associate Professor of Remote Sensing & Geospatial Analysis

- Expertise and interests related to the science-policy interface, GHG accounting, ecosystem models, transparency and carbon monitoring.

Anthony Moffa, Associate Professor of Law

- Expertise and interests related to international environmental law, non-party participation and market-based mechanisms, the Arctic.

UMaine-led delegation of students, faculty attending UN climate summit

A University of Maine-led delegation of students and faculty will witness world leaders, diplomats and experts negotiate global policies to address climate change at a United Nations summit from Nov. 7–18 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt.

By attending the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) 27th Conference of the Parties (COP27), graduate students and faculty from UMaine and the University of Maine School of Law will learn first-hand how delegates, scientists and other stakeholders devise initiatives to reduce greenhouse gas emissions worldwide and help countries mitigate the effects of global warming.

Delegation members also will have the opportunity to help write statements to present to country negotiators and network with high-level diplomats, fellow scientists and lawyers, and other stakeholders during the summit. Additionally, they will watch as research from UMaine and other institutions informs policy decisions on the world stage. For some faculty, observing negotiations will support their own climate change and global policy studies.

The delegation is co-headed by Cindy Isenhour, an associate professor of anthropology and climate change, and Nicholas Micinski, an assistant professor of political science and international affairs. Other members from UMaine include Adam Daignault, E.L. Giddings Associate Professor of Forest Policy & Economics; Daniel Hayes, an associate professor of remote sensing and geospatial analysis; Gabrielle Hillyer, a Ph.D. student in ecology and environmental scientists; Julia Hiltonsmith, a Ph.D. student of anthropology and environmental policy; and Victoria Markiewicz, a master’s student with the School of Policy and International Affairs. The members from Maine Law are Anthony Moffa, an associate professor of law, and Mikala Bolmer, a J.D. candidate.

“This is an absolutely incredible opportunity for the University of Maine and for graduate students in particular,” Isenhour says. “I think it’s a real opportunity for higher education to take a leadership role in climate mitigation. Opportunities like this are also just priceless for students to learn about climate governance.”

During COP27, Isenhour will provide scientific expertise to negotiators participating in the technical workshops of the Global Stocktake. The Paris Agreement includes a provision to “take stock” of progress on global goals for emissions and adaptation every five years. Isenhour, who has studied the politics of carbon accounting for five years, says she plans to “share information during the technical dialogs about alternative carbon accounting systems that can help to raise ambition and contribute to climate justice for developing economies.”

The summit also will feature discussions surrounding other aspects of carbon monitoring, public and private financing of climate change mitigation efforts, research, water governance, land use, renewable energy and other technologies, migration and refugees, equity and justice, and resilience and sustainability, all of which UMaine and Maine Law delegation members can attend.

Government and nongovernment delegations will host their own workshops and booths about different climate change-related issues and policies to address them, and their work to help tackle the problem.

“The importance of COP27 to the future of our planet and to the education of the next generation of climate policy leaders from UMaine and Maine Law cannot be understated,” Moffa says. “Our environmental and oceans law program will join a select group from the U.S. legal academy whose research will directly contribute to, and benefit from, international climate negotiations.”

The UNFCCC awarded UMaine observer status last year during COP26. As a research and nongovernmental organization, UMaine will join the meetings as a member of the Research and Independent Non-Governmental Organizations (RINGO) constituency. Isenhour serves as the RINGO representative to the technical workshops on a key aspect of this year’s negotiations, the Global Stocktake. This allows her to provide research-based guidance for global carbon accounting.

Members of the group are not present to negotiate or advocate specific political positions, but to provide scientific information or to study the negotiation process. UMaine joins a list of RINGO organizations that include top-ranked universities and nonprofits from across the U.S. and the world.

UMaine’s application for observer status came after several UMaine faculty and students were given the opportunity to attend the UN Climate Negotiations in 2017 and 2018, made possible with assistance from Dan and Betty Churchill. Among the members of the UMaine-led delegation to COP27, however, Isenhour is the only one who previously attended a UN climate summit.

“We appreciate the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change has granted us observer status and recognized UMaine’s leadership in climate change and global policy research and education,” says President Joan Ferrini-Mundy. “By attending COP27, graduate students from UMaine and Maine Law will gain knowledge and connections that will better equip them to help study and understand the effects of climate change and increase global sustainability as future scientists, policymakers and perhaps even world leaders.”

Funding Acknowledgement: The UMaine/Maine Law delegation to COP27 extends our sincere gratitude to the University of Maine Climate Change Institute, the Dan and Betty Churchill Exploration Fund, The School of Policy and International Affairs, and Maine Law for their support of this important educational and research opportunity.