Ice in Fire: Frozen Climate Records Inside a South American Volcano -Tupungatito Expedition 2012

Ice in Fire: Frozen Climate Records Inside a South American Volcano – Tupungatito Expedition 2012 (TE2012)

The CCI component of the Tupungatito Expedition is supported by a generous gift from the Garrand Family of Portland, Maine.

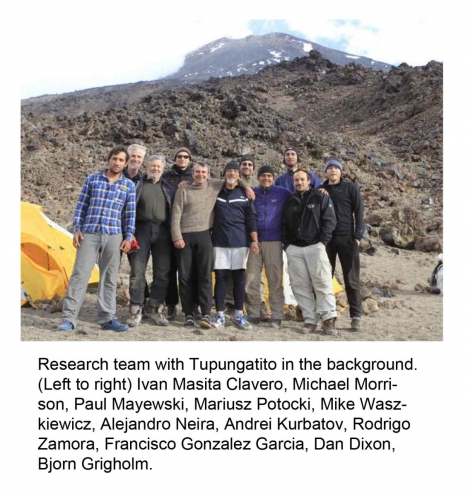

Climate Change Institute (CCI) at the University of Maine (field leader Paul Mayewski, Andrei Kurbatov, Bjorn Grigholm, Mariusz Potocki, Dan Dixon, Michael Morrison and Mike Waskiewicz) and members of the Centro de Estudios Cientifocs (CECS) from Valdivia, Chile (field leaders Gino Casassa and Rodrigo Zamora, Alejandro Neira, Ivan Clauvero and Francisco Gonzalez).

Blog Date: 1/11/2012

South America is in the midst of dramatic changes in water resources and is at particular risk for future abrupt climate change as a consequence of greenhouse gas warming, recovery of the Antarctic ozone hole, and increased industrialization in both hemispheres. Understanding the past and present climatic behavior of high mountain regions in South America is critical for developing appropriate mitigation and adaptation policies for water usage and for predicting future climate change. The reconstruction of past climate conditions provides essential historical context for natural climate variability (a time before human influences) that can be implemented to gauge the relative impact of human activities on the physical and chemical climate system. Ice core records provide the most robust method for reconstructing climate in the absence of instrumental records, which are very rare and of short duration in remote regions such as the Andes.

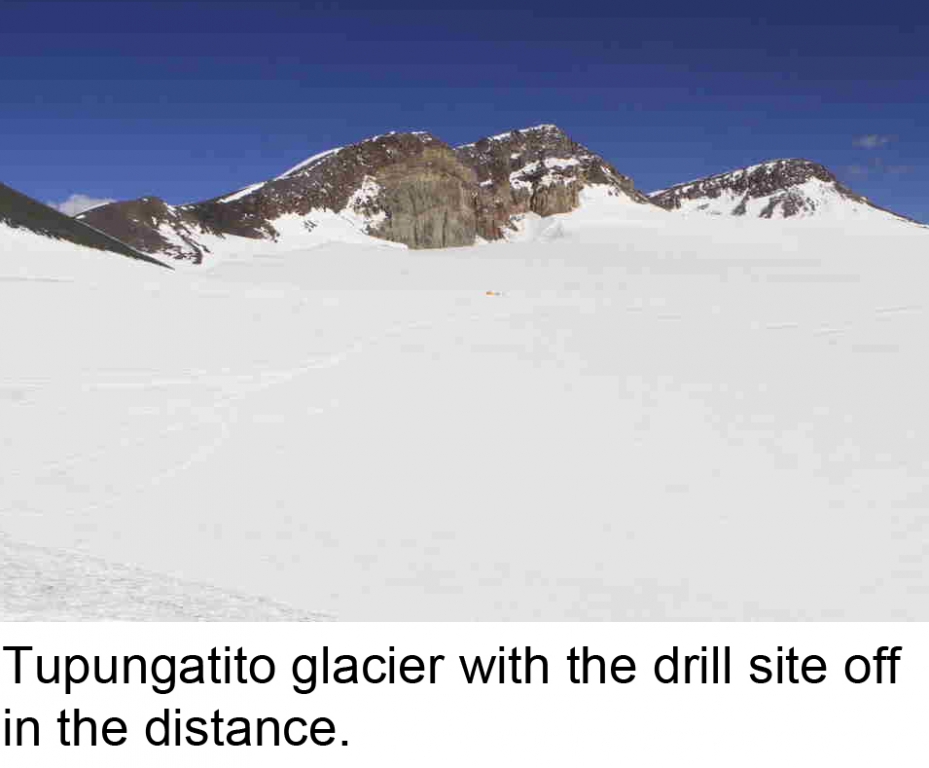

Tupungatito is a high elevation (18,909 ft, 33 degrees 25 minutes South; 69 degrees 48 minutes West) volcanic crater that is particularly well located for monitoring changes in the El Nino – Southern Oscillation, which is a major component of ocean-atmosphere circulation in the tropical Pacific and beyond; major atmospheric circulation patterns such as the easterlies and westerlies; and human- source pollutants from industrial, urban and agricultural activities in South America. A Tupungatito ice core will add to the limited collection of ice cores outside the polar regions. These low-mid latitude climate records are crucial for interpreting global climate change from the equator to the Poles. Tupungatito and surrounding Andean glaciers are also a primary source for water to major population centers, such as Santiago, Chile. Recent research conducted by Gino Casassa reveal that Tupungatito glacier has retreated since the 1970s, coinciding with the vast majority of South American glaciers.

The expedition team, which we call TE2012, is comprised of members from the Climate Change Institute (CCI) at the University of Maine (field leader Paul Mayewski, Andrei Kurbatov, Bjorn Grigholm, Mariusz Potocki, Dan Dixon, Michael Morrison and Mike Waskiewicz) and members of the Centro de Estudios Cientifocs (CECS) from Valdivia, Chile (field leaders Gino Casassa and Rodrigo Zamora, Alejandro Neira, Ivan Clauvero and Francisco Gonzalez). Initial reconnaissance studies by CCI and CECS in February 2010 drill yielded a 40-foot ice core, demonstrating that the site was highly suitable for the recovery of robust environmental records. During the descent from the glacier the expedition team experienced the famous 8.8 Chilean earthquake. Evidence of the event were abundant throughout the mountain valleys.

In February 2011 the team returned to Tupungatito and transported supplies and scientific equipment to the site to drill an ice core to bedrock. CECS radar surveys estimated the thickness of ice at the drill site to be approximately 430 ft. Unfortunately, drilling had be postponed a year due to the extreme weather conditions produced by the 2011 La Nina event. This year’s 2012 Tupungatito expedition arrived in Santiago on January 5th. We will proceed with last year’s deep ice core goal. It will take approximately two weeks to ascend to the glacier to allow for appropriate elevation acclimatization. As the researchers climb to the drill site, they will be supported by mules and horses supplied by local cowboys, known as arrieros. Over the past two years the team has become particularly close with three of the arrieros, Israel Lagos, Marcelino Ortega and Fernando Ortega. In fact, last night we all gathered for a Chilean asado, or barbecue. Currently, the team is located in Maitenes, a small mountain town approximately 28 miles from Tupungatito. All of us are involved in preparing supplies and equipment for the climb. This year we hope to have a snowmobile on site to transport close to 1 ton of supplies across the glacier to the drill site. The next couple of days will be dedicated to taking the snowmobile apart into sections not exceeding 100 pounds each so that the mules can safely carry the load. We expect it will take five mules to carry all of the parts to the glacier and several days to reassemble the snowmobile. Earlier today, the arrieros reported that a bridge on the way to the trail head was blocked by debris due to the heavy rainfall that occurred two days ago. It is expected that bridge will be passable in a few days.

Blog Date: 1/14/2012

Yesterday afternoon we reached our second campsite, Agua Azul or Blue Water. To get there we hiked about six miles along the beautiful Colorado Valley. We camped on an ancient Tupungatito lava flow and had our first glimpse of our route up to the drill site for this season. Agua Azul gets its name from a nearby glacial stream, which provides us with readily and easily obtainable water. At future campsites, snow will have to be melted for drinking water. Yesterday, we gained about 3,000 feet and our current altitude is approximately 10,330 feet. We plan to stay at Aqua Azul for 3-5 days acclimatizing and preparing equipment. Our next campsite will be at roughly 13,780 feet. It is crucial that we take our time ascending the mountain, assessing each member’s health as we climb.

We could not have gotten our supplies and equipment this far up the valley without the help of the Arrieros (Chilean cowboys) and their eight horses and 28 mules. In addition to transporting our gear, the Arrieros help us cross the Azufre River. In the past, we have been given a horse or mule with which to cross. This year, however, the water levels were low enough for us to wade or jump across. Unfortunately, despite the low river level, one of the mules slipped and fell in. The mule was completely unhurt and just got a little wet, as did our supplies. The low level of the river is likely the result of an unusually dry year. With the exception of the heavy rain that blocked one of the mountain roads at the beginning of our expedition it has hardly rained at all this year. Earlier today the Arrieros returned to our first campsite to gather our remaining gear. It’s incredible to think that on average each of the pack animals is carrying about 100 pounds.

A view of Tupungatito this morning revealed the slopes covered in snow. The snow may or may not remain in a day or so, but it is a reminder that we may encounter very deep snow on the glacier. Tomorrow the Arrieros will arrive with the disassembled snowmobile. If there is heavy snow on the glacier, the transportation of the snowmobile will have been well worth the effort. The snowmobile could reduce the expedition time on the glacier by 10-14 days. In the next couple of days the Arrieros will also ride up and assess the snow conditions on Tupungatito´s slopes and in the crater. The Arrieros’ horses and mules are strong enough to blaze a trail through thick snow to last year’s camp and storage site on the edge of the glacier at roughly 18,270 feet. During the past couple of years that we have worked with Arrieros we are continually impressed by their resourcefulness in the mountains.

Blog Date: 1/23/2012

Yesterday we reached the camp at 13,780 feet. It´s a small, flat, sandy area perched on a cliff within the Tupungatito lava flows. The view is spectacular, encompassing the Colorado Valley and many snow-capped mountain peaks. The two peaks that dominate the landscape are Tupungato (about 21,700 feet) and our research site, Tupungatito (about 19,000 feet). During the last few days Tupungatito´s volcanic nature has become more pronounced as its characteristic fumaroles, or smoke emissions, have increased.

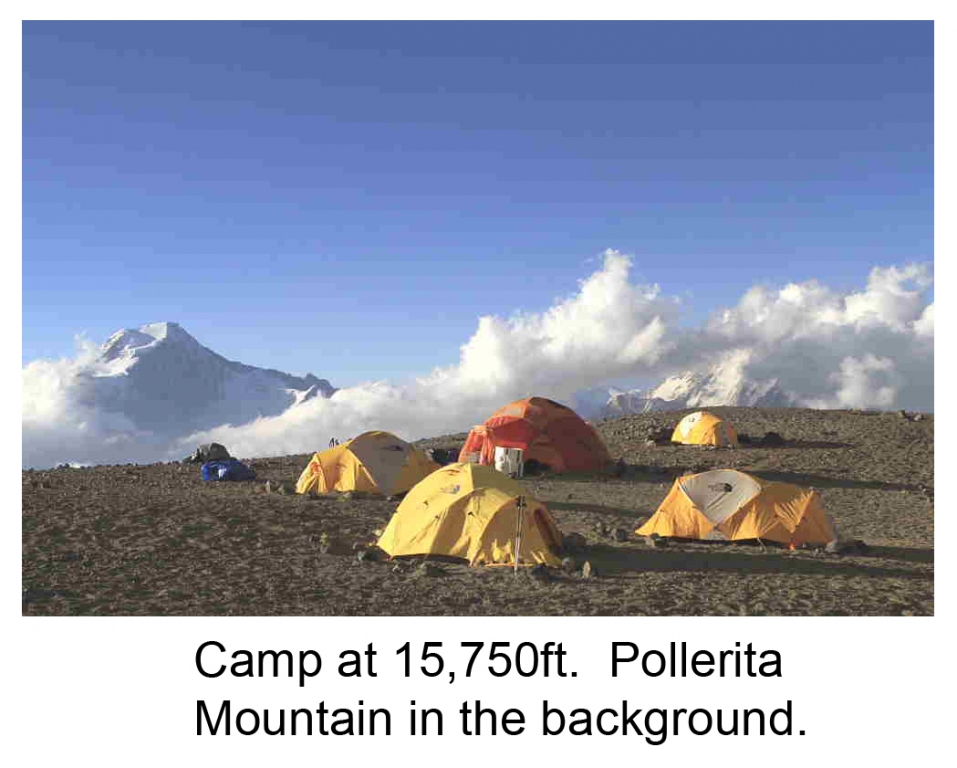

The only downside to our camp location is that it lacks easily available water. We are relying on the Arrieros to bring water from our lower camp every couple of days. The plan is to remain in our current location for the next three days, giving us time to acclimate before we head to the next camp at 15,750 feet. During this time the Arrieros and their pack animals will continue to transport our gear to the higher camp. This morning they left with the majority of the snowmobile parts.

Much of the snow that covered the slopes of Tupungatito has disappeared and the last few days of weather have been beautiful with plenty of sunshine. We continually monitor weather forecasts at the higher altitudes to get a better understanding of the conditions we may experience at the drill site on the glacier. The latest forecast we received reported wind speeds atop the mountain will increase significantly over the next few days, increasing from 25 mph to 45mph. On these windier days the windchill factor could drop to minus 26 degrees. Obviously, we hope for calm weather when we reach our drill site, but we have certainly come prepared for rough conditions.

Blog Date: 1/31/2012

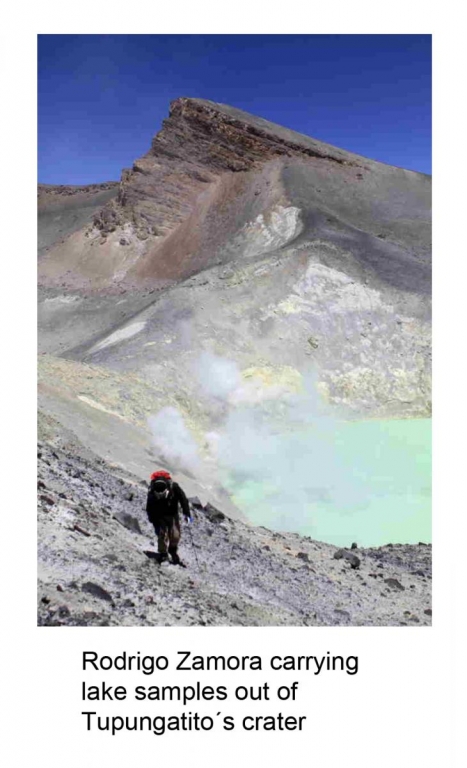

It is now our fifth day at 15,750 feet. We had originally planned for 3-4 days at this camp, however, in the last few days the winds above 16,000 feet have steadily increased, with gusts up to 55 mph. We are waiting for a break in the weather to begin setting up our larger tents next to the glacier. In the meanwhile, our team has begun organizing gear and building the drill at the 18,270 foot camp. The hike to the camp involves climbing up steep slopes to the rim of Tupungatito crater, where you get an amazing view of the Andes and can peer into Argentina. It’s another mile following the crater rim to reach the glacier. In addition to breathtaking views of the mountains, once on the rim you can look down into one of Tupungatito’s craters and see an incredible bubbling volcanic lake. The lime-green color of the water, the yellow, sulfur-stained crater walls, and the constant hissing of escaping toxic gases convey a beautiful but hostile Martian-like environment. Ironically, these are the types of environments in which many biologists are searching for life. The organisms that thrive in extreme environments like Tupungatito’s acidic volcanic lakes are referred to as “Extremophiles.” Yesterday, our team assisted a CECS biologist in the collection of water samples from the lake. We had to wear filtered masks and goggles as exposure to the fumes can be very hazardous. The experience was fantastic even though hauling 50 pound water containers up steep, sandy slopes at 17,000 feet was exhausting and the mask seemed at some points to limit oxygen as much as the toxic gases. The biologist is currently heading back to his lab in Valdiva and we’re all very interested to see what he finds.

Whether we are acclimatizing, preparing our gear, or jumping into craters, our Arriero (cowboy) friends have continued to assist us along the way. They recently carried up roughly two-and-half weeks worth of food. The arrival of new supplies like bacon, cheese, tuna, and (for some) marmite was thoroughly celebrated. It’s always nice when the Arrieros come to camp. They’re always in great spirits, laughing and joking around. Their laid-back nature makes it easy to forget how difficult their profession is. It requires a great amount of skill and stamina, and yet they make it look simple. We’re all very curious about the Arriero way of life and how it has been passed down from generation to generation and how it coincides with the modern world. Sadly, the Arrieros say the next generation will most likely choose other professions as Chile’s economy and urbanization have created job demands elsewhere. During their last visit it was nice to see that they were accompanied by a young Arriero named Luis.

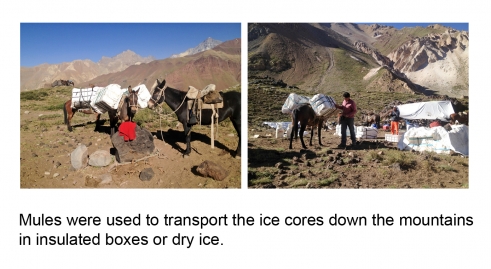

In addition to preparing for the ascent of Tupungatito and the ice core drilling, we are also continually planning the descent from the glacier. The 400 feet of ice cores we plan to collect will be carried on the mules in insulated boxes with dry-ice for two days to the safety of a freezer truck at the Colorado Valley trail head. We just heard today that the bridge that caused us delays a couple weeks ago is again flooded. If it remains flooded the truck will be unable to cross so we will need to begin planning for that possibility. The dry ice can only protect our ice cores from melting for 24-36 hours.

In the past couple of days two team members have had to leave. Rodrigo Zamora left to conduct radar surveys in northern Chile on another CECS expedition. Dan Dixon is returning home to Maine to his wife Erika to await the arrival of their first child. Our best wishes go out to the Dixons.

Blog Date: 2/15/2012

The last two weeks have been extremely busy and productive. In the last blog entry we were about to leave for the 18,270-foot camp. We headed up on Feb. 1 and although we had waited for a break in the winds we were met by some strong gusts. The campsite was situated on a large, steep, sandy bank next to the glacier, which provided us with an excellent vantage point to plan trips onto the ice. There were hardly any rocks available so the tents had to be fastened with sand bags.

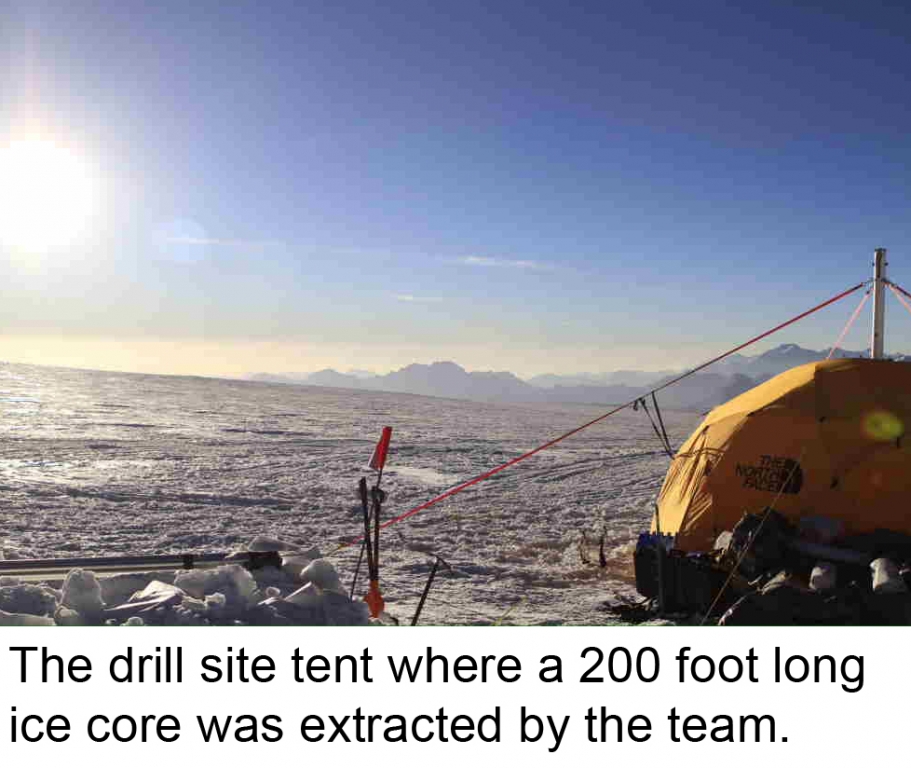

Once we had our shelters built and had set up our stove to begin melting snow for drinking water, our first priority was to get the snowmobile put together. We designated our kitchen tent as the construction site. Francisco and Masetta did a fantastic job, managing to finish in two days while working with limited space and in sub-zero temperatures. During this time the rest of the team was working on finding a safe route to the drill site. We were surprised to find many more crevasses on the way to the site than last year. For recreational travel across a glacier this is not a problem, a team just needs to be roped and will most likely only cross individual crevasses once or twice. In our case, we were planning on carrying heavy equipment with a snowmobile many times across the glacier. Due the multitude of crevasses and the uncertainty of how the snow bridges would hold up, we opted to change our drill to a safer and closer location. The new drill site was of the same quality as the original site; however, the ice core would be a bit shorter – a small price to pay for the safety of our team members.

The snowmobile worked perfectly, making the transportation of our gear much easier. We fastened 3 sleds together and attached them behind the snowmobile. What would have taken us days to prepare and carry to the drill site took only hours. We also used the snowmobile as a fast and fun way to commute to work. Before we could begin drilling we had to set up the drill tent, build the drill itself and dig a trench (with a chain-saw) to store the ice cores in. Although the glacier is cold, direct sunlight at these altitudes can heat surfaces, so it’s best to cover the ice cores during the day.

We began drilling on Feb. 4. Drilling is as much an art as a technical skill and we were very lucky to have Mike as our driller. He has a vast amount of experience, having drilled all around the world. In addition to retrieving cylindrical ice segments from the glacier and storing them, the ice cores also needed to be examined for particular ice properties, such as summer melt layers. We always handled the ice cores carefully and cleanly, wearing clean suits, masks, and gloves. We use clean suits because we do not want to possibly contaminate the chemistry of the ice, although we actually only use the outside of the ice core to measure stable water isotopes, a possible temperature indicator that can reveal warmer vs. colder time periods, which cannot be contaminated by handling the ice. We use the inner part of the core, which never comes into contact with the drill or handlers, for major soluble ions and trace elements, such as sodium, sulfate, and lead. These types of chemical species can be indicators of natural and/or anthropogenic sources. Our job when we get back to Maine is to see how the ice chemistry has changed as we move from the top of the core (the present time) to the bottom (the past). Overall the drilling went very smoothly and we finished on Feb. 7. As expected, the ice core at the new site was shorter, reaching a depth of 200 feet.

Now that we had the ice core, the difficult task of transporting it frozen and intact back to Santiago had begun. Our plan was to have the mules carry the ice in insulated boxes down to Aqua Azul camp where they would be repacked with dry-ice to maintain sub-zero temperatures for the rest of the trip. Paul took a test trip with ordinary ice down first to make sure every thing was in place for transfer. This included the delivery of dry ice, access to a freezer truck at the trailhead, and open roads to the Santiago freezer. Once Paul reported the test had been a success, we packed the ice cores and sent them down the mountain. Michael accompanied the ice cores to Santiago and reported last night that the ice was safely sitting in a freezer. It was extremely relieving to hear that the ice was safe. During the last couple years the team, led by Paul, has worked very hard to recover this ice.

Andrei, Mariusz, Masetta, and I traveled down from the glacier yesterday and are currently staying at the Agua Azul camp. We will remain here a couple more days to wait for our equipment, which the Arrieros will take down from the glacier.

Blog Date: 2/18/2012 – Getting the Ice Cores Home

We thoroughly enjoyed the time we spent in Maitenes waiting for the Arrieros to join us with the remaining equipment. We enjoyed beautiful weather and delicious meals, which always included fresh fruits and vegetables that are very difficult to maintain in the field. We spent our time assessing the equipment we had with us for possible damage. Obviously, our tents are subjected to harsh conditions such as high velocity winds, volcanic soils and dusts, and strong UV radiation, and it is very important that we inspect each item carefully to ensure it is adequate (or not) for another field season. Although we were enjoying nice conditions, the Arrieros were not so fortunate with the weather. Up at the top of the mountain they were encountering some strong winds and snow. Luckily, they were able to get the last of the gear down in one trip and they were as happy as we were to return to Maitenes.

Once all the gear was reunited, we inspected everything and separated the essential gear (drill, tents, sleds, rope, etc.) that we were returning to Maine and insured it was all safe for travel. We gave all the remaining unused food to the Arrieros as an extra thank you for their great job. During this time, we were also communicating with Paul and Michael. They gave us a more detailed account of the ice cores’ safe transport to Santiago and present condition.

Currently, the ice cores are sheltered in a freezer in Santiago waiting to shipped by sea from Valparasio to Boston. It’s incredible to think that this ice core, which began as snowflakes hundreds, or perhaps thousands, of years ago on top of a volcano in the middle of the Andes, will now travel north into the tropics across the equator and come to rest in a laboratory in a small town in Maine. Of course, part of our job will be to determine exactly how long the ice resided in the Andes.

As we were finishing our packing the Arrieros kindly invited us to their home to enjoy a farewell assado (barbeque). The food was excellent and included grilled goat, avocadoes, and freshly baked bread. We toasted to a successful field season and discussed potential future endeavors in the Andes. Michael reported there was no damage to any of the ice cores, which is incredible considering the terrain they were transported over. Again we would like to thank the Arrieros for an amazing job; working at high-altitudes is extremely difficult especially when handling delicate ice in the mountains.

Blog Date: 3/13/2012 – Core Meltdown

With the ice cores safely on their way back to Maine, we are making the necessary preparations for their processing and analysis. The extraction of ice from the glaciers is only part of the story; the next chapter begins in the freezer at UMaine’s Climate Change Institute, where the ice will be divided into multiple sections. Each section is designated for a different type of analysis. At CCI we will literally be counting atoms, focusing on the stable isotopes of water and a suite of trace elements.

Stable water isotopes, which include oxygen isotopes (16O and 18O) and hydrogen isotopes (H and 2H), can give us information about changes in temperature and moisture sources at Tupungatito glacier. The stable isotopes will show us annual temperature changes (e.g. winter/summer) as well as long-term variations in regional temperature. We will collect isotope samples at 3-centimenter increments throughout the approximately 60-meter ice core, giving us roughly 2,000 samples. Trace element analysis involves determining the concentration of numerous elements including aluminum, iron, calcium, sodium, sulfur, copper, zinc and lead, to name a few. These different elements can reveal regional environmental changes such atmospheric dust concentrations, marine air-masses (e.g. sea-salts), volcanic emissions and human pollutants. The trace element samples will be run on an Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) instrument designed to discern concentrations as low as parts per quadrillion. In addition CCI has developed an in situ laser ablation system that does not require the ice to be melted. The laser ablates the ice surface and the subsequent gas is immediately analyzed by the ICP-MS instrument. Remarkably, the laser system allows a one-meter section of ice core to yield around 100,000 continuous samples compared to about 100 samples if melted — a 1,000-fold increase! This increase in sample resolution is particularly valuable in the deeper sections of the ice core where ice is more compressed and annual layers are much thinner. Sections of the ice will also be sent to our scientific collaborators for analysis of black carbon (an indicator of biomass burning and human pollutants) and for biological samples (CECS will be looking at the bacteria that live on glaciers and how they have changed over time).

As analyses are completed, the data collected will help to uncover how local climate features such as temperature, precipitation, storms and atmospheric chemistry have changed over time at the site and surrounding region. We will be able to add and compare it to other regional-global scale climate records CCI has collected over the years. Each new climate record adds another piece of the puzzle to how and why our planet’s climate has varied in the past and can help give us context necessary to know how it may change in the future. All of us feel very privileged to be a part of this endeavor of discovery, whether it be finding answers or raising new questions.

We would again like to thank Garrand for their support in making this expedition possible.