A Kinematic Survey of Khumbu Glacier, Nepal

Khumbu Glacier, Nepal

A Kinematic Survey of Khumbu Glacier, Nepal: A contribution to the study of how global warming affects glaciers in the Himalaya and the consequences for massive populations in Asia

Field Members: Adam Barker (University of Washington, PhD Candidate) and Lauren Wheeler (University of Maine, Master’s student)

Funding: This project is funded by an NSF grant awarded to Bernard Hallet of the Department of Earth and Space Sciences at the University of Washington. My travels to and from the field site are generously funded through the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine by the Bingham Trust Fund and the St Elias Erosion and Tectonics Project (NSF Award Number: 0409162).

Tuesday, May 29, 2012

The tempo of erosion in the Himalaya has received considerable attention because of the important role erosion plays in the development of the range, and more generally, because of the broad interest in the rich interactions between tectonics, topography and climate that govern mountain building. Little is known, however, about rates of erosion at the heavily glaciated crest of the range, and there is no consensus on whether glaciers accelerate or impede erosion in the region. Furthermore, the glaciers that dissect the range typically disappear under a thick debris cover at lower elevations. This debris cover is sustained by input of rock fragments to the glacier, which must result from glacial and periglacial erosion of the catchment. The downvalley emergence of debris from the interior of the glacier is controlled by the ablation rate, the debris concentration in the ice and the ice velocity. In turn, supraglacial debris strongly impacts ablation, and hence affects the mass balance, spatial extent, and response to climate change of the glacier.

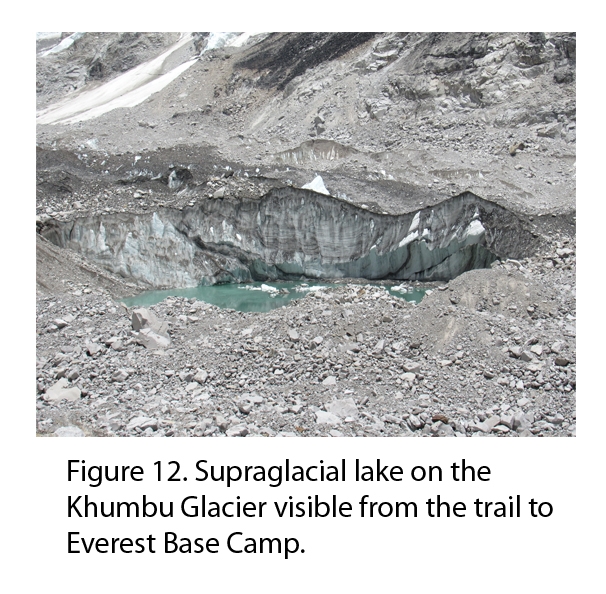

Little is known about the interaction between debris and ablation in spite of records that extend to the 1920’s on Khumbu Glacier, Nepal, at the base of Mount Everest. This is especially true for the lower reaches where the glacier rates of thinning have averaged ~0.5 m/yr between 2002-2007 (Bolch et al., 2011) and where debris cover is thick (>2 m; Nakawo et al., 1986), but difficult to measure. Long-term glacier thinning is linked to both the mass balance and glacier dynamics. Results from Peter et al. (2010) show that Khumbu Glacier flow velocities are decreasing over time even to stagnation and that on most glaciers in the region, areas of inactive ice can be inferred. With this in mind, we propose to obtain GPS velocities on the poorly constrained lower Khumbu to shed light on ice dynamics and to improve our understanding of the state of health of the Khumbu Glacier.

Recent and future work on this project will determine contemporary erosion rates for the Khumbu basin, at the foot of Mt Everest, through a detailed examination of the fluxes of ice and debris in this basin. Recent scientific advances in remote sensing and an unusually rich, available environmental database make it possible to determine these fluxes on three time scales: during the 2-year duration of this project, ~60 years and ~10,000 years.

This study will advance knowledge and understanding of the interactions between snow and debris that sustain massive low latitude glaciers and shape high mountains. It is also likely to yield more general insights into the co-evolution and interdependence of valley glaciers and topography. The primary investigator for this study, Bernard Hallet at the University of Washington, also works in close collaboration with Peter Koons, my advisor, on the St Elias Tectonics and Erosion Project (STEEP), the project that funds my research. Adam Barker, the PhD candidate at the University of Washington working on the Khumbu glacial erosion project works with Bernard Hallet and is also a contributor to STEEP.

This project will be a valuable experience for me and will be applicable to my master’s thesis work, which is focusing on the effects changing glacial loads due to climatic variations on the topography, strain distribution, and evolution of the St Elias Mountains located in southeast Alaska. The field work on Khumbu Glacier will give me an opportunity to observe processes of glacial erosion and uplift that occur in southeast Alaska. I will also gain valuable experience through the use of reanalysis data and modeling of glacier dynamics and glacial extent as functions of climate. One important objective of my master’s thesis is to develop a shallow ice sheet approximation for southeast Alaska using the University of Maine Ice Sheet Model from Pleistocene to present. I will use NCEPII and ERA-Interim reanalyses as the initial climatic input for the model. The model results will be constrained using observations of sea level rise and geomorphic features in Alaska. The shallow ice approximation from Pleistocene to present will then be used in a three-dimensional mechanical model to address 1) How the time dependent mass distribution influences the strain distribution and 2) How the observed constrained spatial variations influence the strain distribution.

The proposed research also promises to contribute to the understanding of how global warming affects glaciers in the Himalaya and the probable consequences for massive populations, including 1) initial increase in runoff due to the accelerated melting followed by diminishing supplies of fresh water from the dwindling glaciers, and 2) increasing threat of Glacial Outburst Floods from ice-dammed lakes formed by rapid glacier retreat. This work will also contribute to the goals of several organizations contributing their data for the Khumbu region (Pyramid Meteorological Network, the Nepal Climate Observatory at Pyramid, and others), which include 1) evaluating the mass and energy balance of glacial environments as well as the related human risks (Glacial Outburst Floods), and 2) understanding debris covered glaciers and the role of debris in ablation processes.

Text Credit: Adam Barker, Bernard Hallet

Friday, June 1 to Saturday, June 2

After about 36 hours of travel Adam and I finally made it to Kathmandu on Friday and met up with our guide, Bhairab, at the airport. Bhairab works with many different scientists from several different institutions who come to Nepal for field work. We were to stay in Kathmandu for the night and then leave for Lukla early the next morning. The drive from the airport to the hotel was quite the experience, there appears to be no order in the streets of Kathmandu. There are no lines dividing the road, no stop signs, no street lights, and the roads are in worse disrepair than the ones back home in Maine. Once we settled into the hotel Adam and I went out for water and a brief tour of Thamel, the tourist district. This will be Adam’s third field season in the Khumbu and he knows Thamel and the trekking route in the Khumbu region pretty well by now.

Saturday morning we left early for the domestic airport, which meant driving through Kathmandu once again. You’re not exactly given a time for your departure on your boarding pass and the wait for your plane can be very long due to weather delays and making up for missed flights. Fortunately we only had to wait about 25 minutes for our departure. The skies were a bit cloudy but the transition from Kathmandu to the small rural villages spread out in the mountains was still visible.

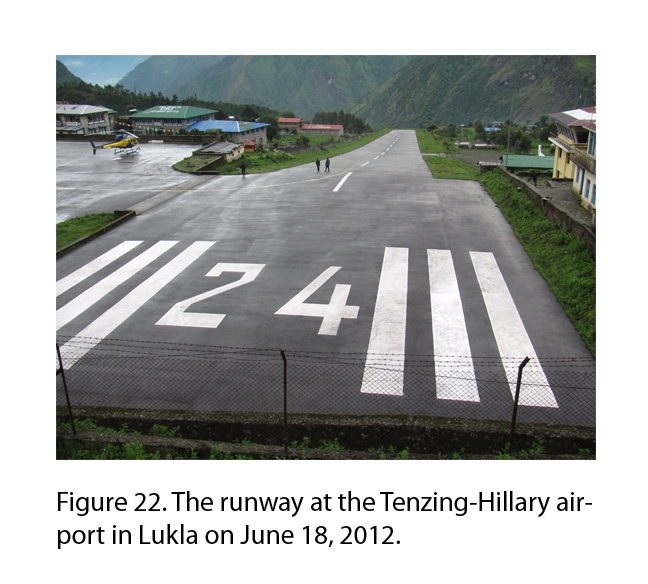

The Tenzing-Hillary airport is known as the most dangerous in the world and upon touchdown it became apparent why, the short runway ends in a cliff on one side and a cement wall on the other and

Adam said that it’s not uncommon to see airplanes with some nose damage. Once in Lukla, Bhairab selected porters to carry our things. Between the two of them they’re probably carrying 75 kilos of gear and equipment. Shortly after the porters left Lukla we followed. We were headed to Phakding, a small town along the Dudh Koshi River and our stop for the night. Lukla is at 2840 m in elevation and Phakding is just below that at 2610 m. The stop at Phakding was for acclimatization and to download data from a turbidity sensor just up the river that Adam had installed during a previous field season.

That night over tea and dinner we discussed the many different hazards that the people in the Khumbu region face. Not only was there potential for Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) but there are landslides, flash floods, earthquakes, severe winds, and forest fires. On our hike to Phakding we saw at least two landslides. One had occurred last year when the area was hit by an earthquake (Figure 3) and blocked the bridge, a path was made around the valley but it took an additional hour to get to the other side. The second had failed without help from an earthquake or heavy monsoon rains and killed several villagers while they were still inside their homes (Figure 4). Another recent event was a flash flood in a valley nearby that killed 20 people, most of whom were enjoying a picnic along the river. Fortunately, the flood was seen by a pilot giving a tour of the area and he was able to communicate with officials and the word spread very quickly through cell phone communication and TV and radio broadcasts. This early warning likely saved many lives.

Sunday, June 3

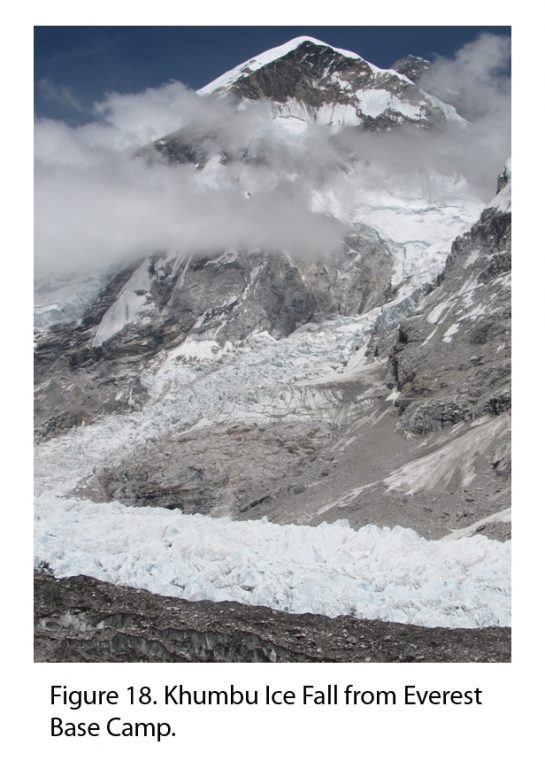

We started out early to Namche Bazar. The weather was beautiful, warm, partly cloudy, and for most of the trek we were accompanied by a light breeze. We entered Sagarmatha National Park and continued up the Dudh Koshi River (Figure 5). At the park entrance they keep track of the number of trekkers that have come through since 1998. In 1998 around 20,000 people went through the park entrance and the number has increased to 34,000 in 2011. 2002 was the lowest year for the park with only 13,000 people passing through. The trek to Namche was quite the climb, Namche sits at 3440 m and the trail is made up of many switchbacks. Along the way I got my first ever glimpse of Mt. Everest! The summit was covered in clouds but some of the mountain was still visible. I’m looking forward to the view from Kala Patthar. Kala Patthar is roughly 3 km to the west of Everest Base Camp and is 5550 m in elevation. Provided the skies are clear we should be able to see all of Mt. Everest, the Khumbu Ice Fall, and Nuptse Peak when we go.

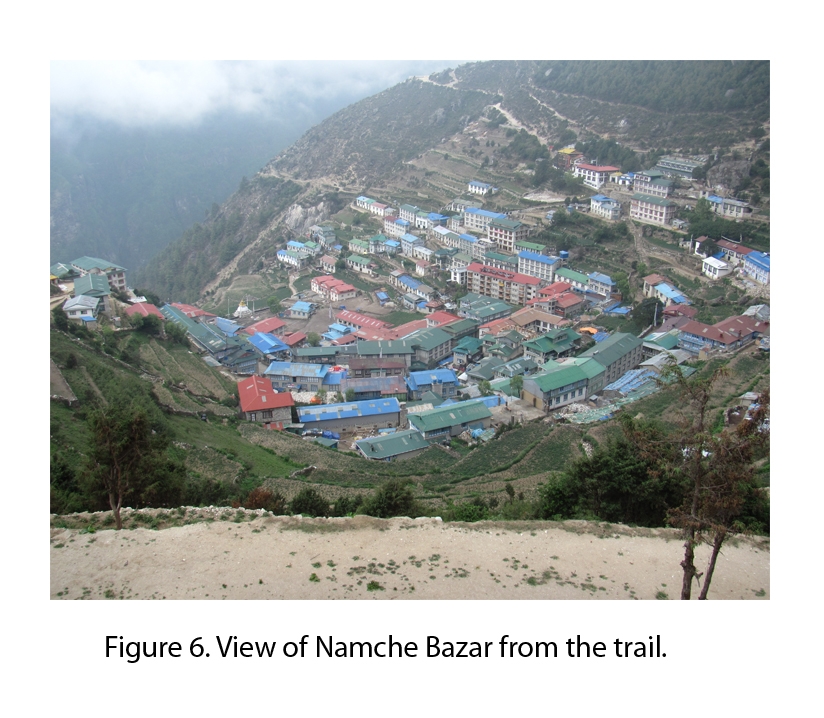

Namche Bazar was rather empty once we arrived and we only met one other trekker. Since Adam has last visited the town has grown a lot, several new buildings have been erected and the center of town has been cleaned up quite a bit (Figure 6). Namche Bazar is one of the bigger towns along the trail to Everest Base Camp and Adam and I went out to purchase a couple of supplies around town. I was very excited to finally get myself a map of the Khumbu. From the map our route out and back from Lukla to Everest Base Camp and Kala Patthar is approximately 62 miles as the crow flies.

Monday, June 4 to Tuesday, June 5

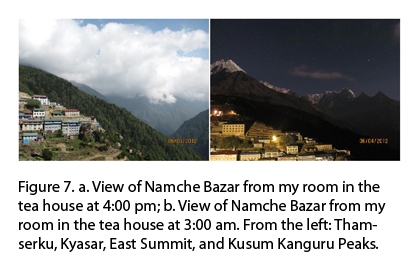

Sleep has been slightly off for all three of us since starting the trek and Monday I woke up at 3:00 am and didn’t go back to sleep. I stayed up and experimented with the camera and Figure 7 is one of the shots that I was able to get.

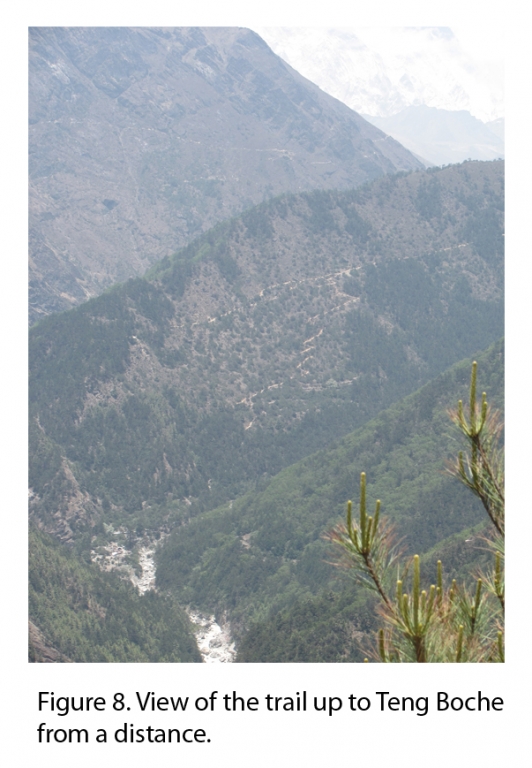

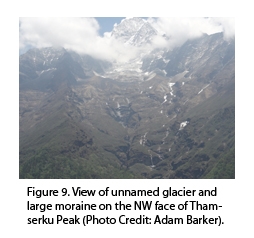

We got a late start on Monday because we stayed in Namche Bazar charging the turbidity station battery. In total it took 17 hours to charge the battery and once complete we left for Teng Boche. Teng Boche is situated on top of a hill, up the valley and across the river from Namche. The hike is long and laden with switchbacks similar to the trail to Namche. Not too long after our departure from Namche we got another glimpse of Mt. Everest. Sadly, it was too cloudy and it’s not visible in any of my pictures but we did have a beautiful view of Thamserku Peak and an unnamed glacier that sat on the NW face of the peak. The moraine is very large and appears to be sharp from a distance (Figure 9). On the glacier-side the moraine is unvegetated and on the distil side the moraine is vegetated. This indicates that the glacier was stable for a long period of time and suddenly and very rapidly retreated from that position.

Once we arrived and were settled in Teng Boche for the night we left to go visit the monastery. Shorts are not appropriate for wearing inside a monastery and by the time that I had returned more appropriately dressed the monastery was closed. Adam, Bhairab, and I continued to walk around the small village, we visited a very scenic open hillside and sat for a while until everyone was cold and hungry enough to return to the tea house.

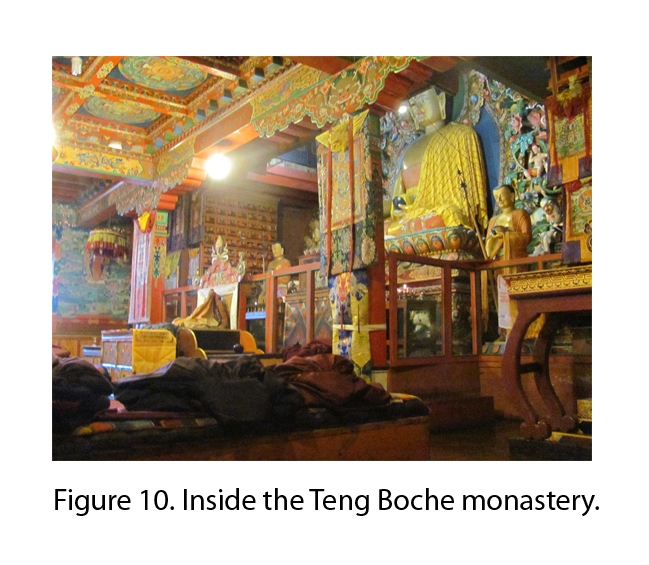

Tuesday morning we were all up bright and early and before breakfast went to visit the Teng Boche Monastery. Inside is very decorated and beautiful. Everything is hand painted with warm vibrant colors (Figure 10). We were served warm masala, a tea similar to chai, while we sat along the wall and listened to the morning readings. After visiting the monastery we left for Ding Boche to collect data from the turbidity station sitting in the Imja Khola and to replace the battery. From the trail you can see the villagers erecting more buildings near the river in spite of the fact that Ding Boche is in a location that’s at a very high risk if there were to be any flooding. Teng Boche to Ding Boche is roughly a 600 m elevation change plus another 100 m to get over the moraine to get to Pheriche (our final destination for the day). This was my first experience with altitude sickness, which was mild but still not pleasant. The arrival at our tea house was welcomed and I ended up sleeping until dinner.

Wednesday, June 6

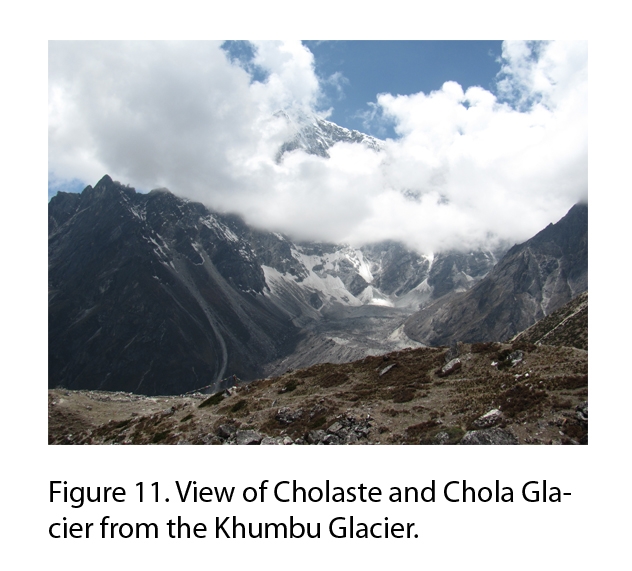

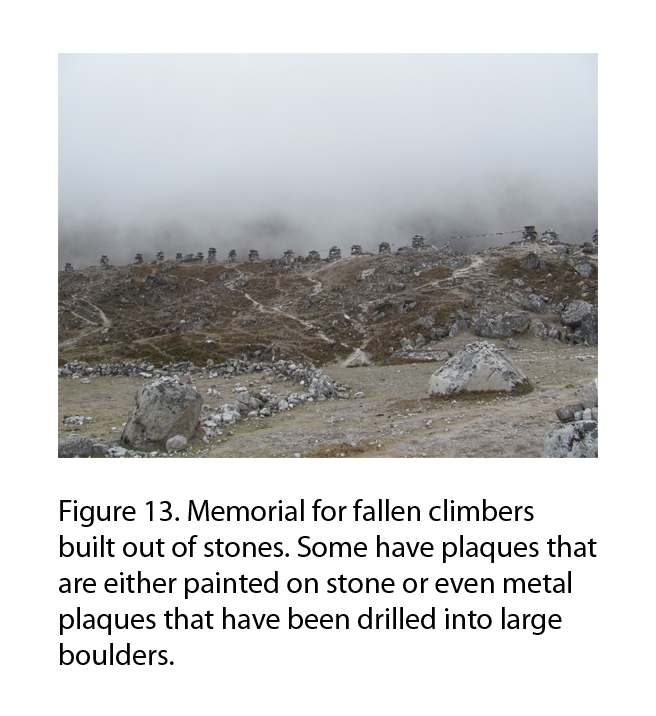

We had a short hike from Pheriche to Thokla which was a nice change after a few of the longer uphill hikes we’ve done. From the trail we had some very nice views, the sky was clear and Cholaste Peak and Chola Glacier were visible. Chola Glacier is a debris covered glacier, like the Khumbu. There are large lateral moraines and it is probably a rock glacier that is stagnant with much debris incorporated into it (Figure 11). The objective for the day was to swap out the battery in the turbidity station and download the data and also download data from the pressure transducer. We were also to collect some temperature loggers that Adam had on a previous trips to the field site installed on the surface of the glacier at 0, 20, and 60 cm depth. This was my first time on the Khumbu glacier which is covered in debris that’s 2-6 m thick in some places based on resistivity measurements that Adam took when he was last in the field. On our trip back to Thokla we passed through a memorial for fallen climbers that is set up along the trail (Figure 13). Many are built from stones off the moraines and are decorated with pictures, plaques, and prayer flags.

Thursday, June 7 to Saturday, June 9

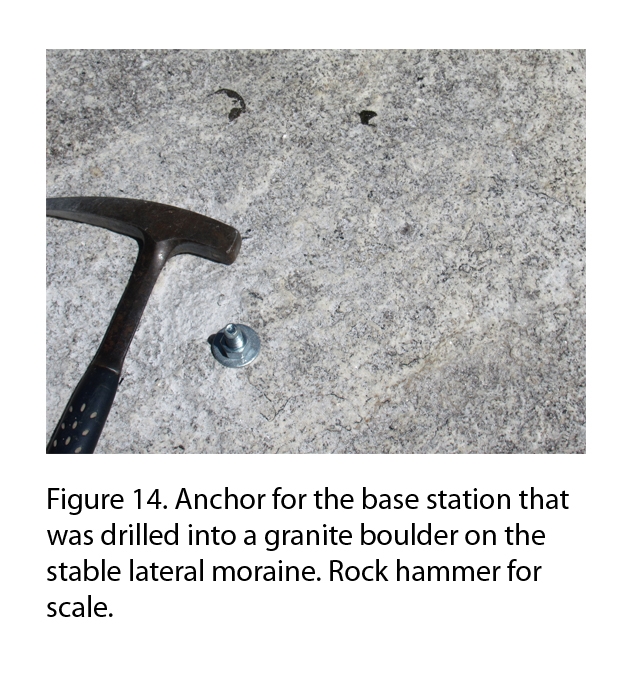

Thursday we hiked from Thokla to Laboche and began the GPS survey of the glacier. Ideally, Adam wanted to put in 15 anchors for the roving GPS stations and 1 for the base station. Once they were all in place we would set up the base station and begin taking measurements at each roving station. Then we would come back three or four days later and resurvey the points to see if between there was any movement. Once we were out in the field we had to scout for a flat rock on the old stable moraine to the east to drill the base station anchor in (Figure 14). Due to the fact that most of the Khumbu Glacier is covered in granite and gneiss boulders it took a considerably long time to drill each anchor and by the time we had gotten to our third roving station both of the batteries for the drill were dead. To charge batteries in the Khumbu you either have to have solar panels or you must pay at one of the tea houses to use their electricity. When our batteries ran out Bhairab kindly offered to hike to Pang Boche and stay overnight to charge the batteries and bring them back Friday afternoon.

Since we were unable to do any drilling on Friday, Adam, one of the porters, and I spent the day walking around the glacier collecting the rest of temperature loggers that Adam had installed during a previous field season. The temperature loggers are buried and collect the temperature every 15 minutes, then when we come to unearth them they are connected optically to the computer to download the data. Some of them we reburied to be collected in the fall but the rest were removed. Bhairab arrived Friday night around dinner with only partially charged batteries which meant that we had to be choosier with the rocks that we drilled into and wouldn’t be able to drill as many roving stations as Adam would have liked us to.

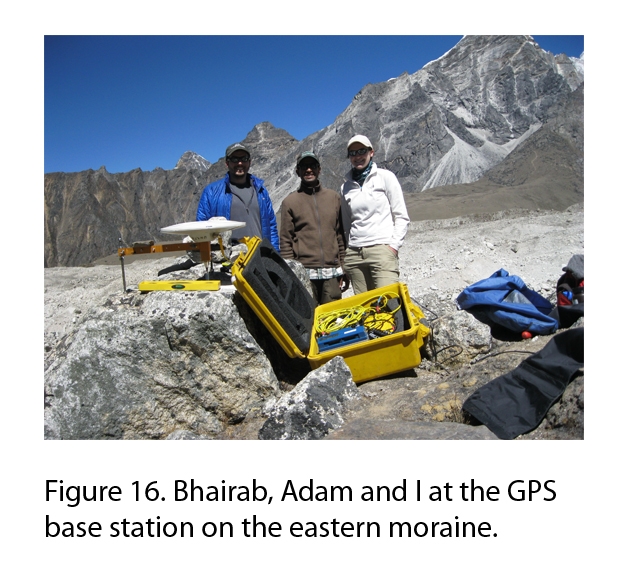

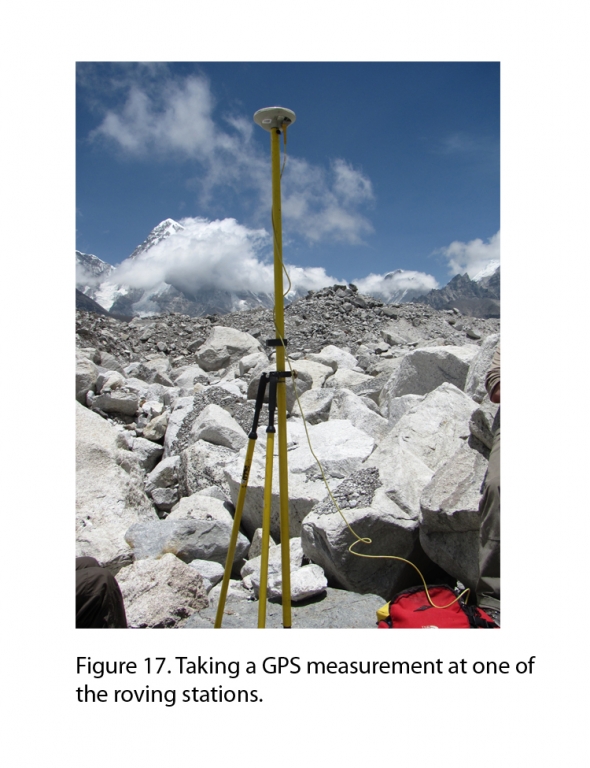

Saturday’s objective was to install as many roving stations as possible and to take measurements at each one. First we had to set up the base station (Figure 16). The anchor was already in place so Adam began programming the equipment while Bhairab and I made sure that the base station was level and appropriately oriented. Once the base station was set up we began our transect of roving stations. The transect was in the center of the glacier and went approximately 1 km to the north of the base station and 1 km to the south. Since we were low on batteries we needed to find a softer rock than granite to drill the anchors into and on the Khumbu this wasn’t the easiest of tasks. Almost all of the rocks are granites or gneiss and the few softer schists that we found were either too small or not in a stable position. We were able to find enough stable schists to install the anchors into and successfully took measurements at 6 anchors installed 1 km south of the base station and 3 anchors installed 1 km north of the base station. Fewer anchors were installed along the northern transect because we had a much more difficult time finding suitable boulders.

Sunday, June 10

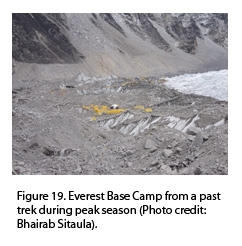

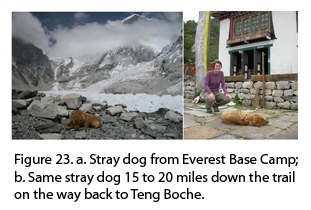

Now that the first set of measurements are complete we have to wait a few days to take a second set of measurements for consistency. While we wait Adam and I get to be tourists for two days and do a little extra trekking. Early that morning we left for Gorak Shep and arrived shortly before lunch. The plan was to leave Gorak Shep for Everest Base Camp (EBC) after lunch. Adam had contracted a cold and decided to stay behind and get some rest so it was just Bhairab and I. The hike from Gorak Shep to EBC isn’t a long one and we made it there in good time. Since the first main tourist season is over EBC was completely empty with the exception of a stray dog.

Along the way back Bhairab pointed out a couple of changes that he has observed over the years. First, that the Khumbu Ice Fall has significantly decreased in size, there is now a large rock face exposed that he says was completely covered in ice 10 years ago. Also, that some parts of the trail we were walking on had moved 10 meters or so away from the glacier. As the Khumbu Glacier melts the trail steepens and erodes away forcing the trekkers to make a new trail further away from the edge.

When Bhairab and I returned to Gorak Shep Adam still wasn’t feeling well and we made plans to go early tomorrow morning and hike Kala Patthar without him.

Shortly after 4:00 am Bhairab and I began our hike up Kala Patthar to catch the sun rise behind Mt. Everest. We arrived at our peak elevation of 5550 m at the perfect time and what a view! Within two minutes we were watching the sunrise behind Mt. Everest. As we were warmed by the morning sun we also enjoyed hot tea and biscuits. We stayed on Kala Patthar for a couple of hours enjoying the view. While we sat on Kala Patthar we witnessed a small avalanche on Pumo Ri, saw a pika, and watched many birds dive straight down the mountain side.

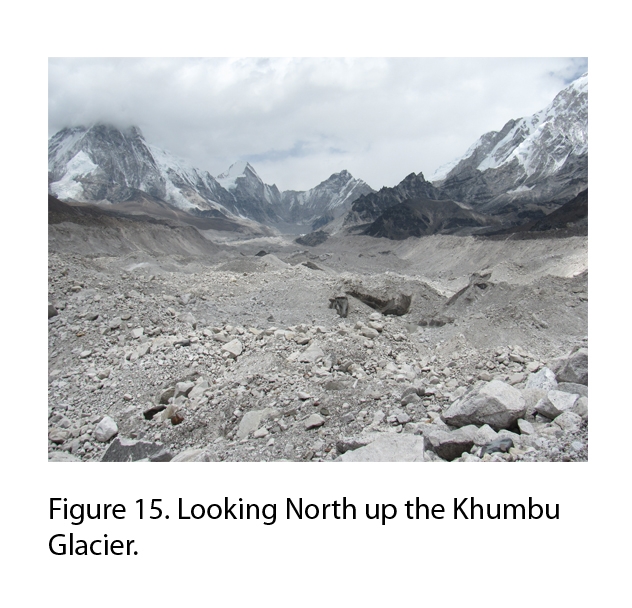

Once we returned from Kala Patthar we collected our things and left for Laboche. On the way back to Laboche we had an excellent view of the Khumbu Glacier where you can clearly see that the glacier is in disequilibrium. The profile of the glacier and the moraines are offset around the middle of the glacier.

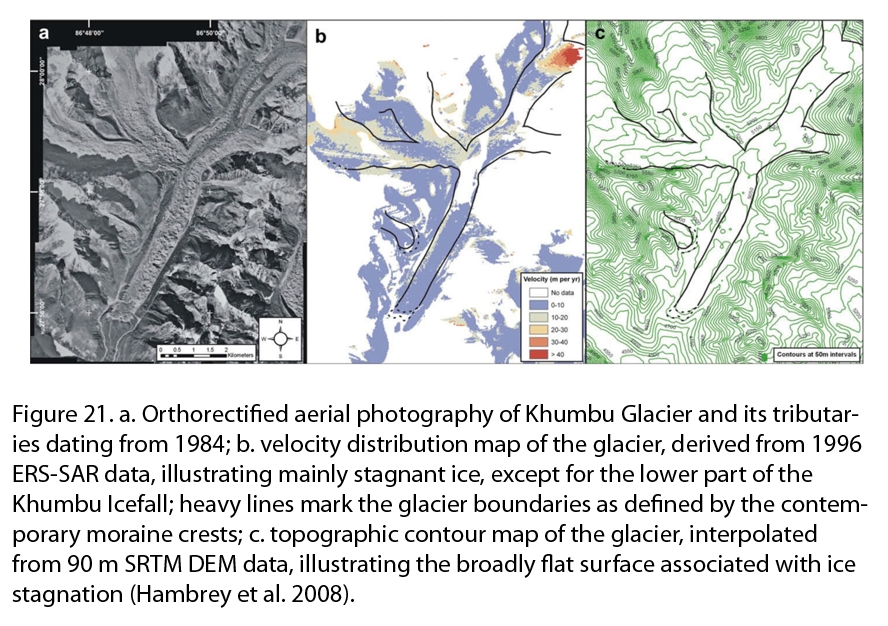

The derived velocity measurements for Khumbu Glacier support previous reports that the lowermost 6 km of the snout are stagnant (Figure 21)(Hambrey et al. 2008). Only immediately below the icefall can any displacement be detected; here velocities reach ca. 40 m/yr where the ogives are developed. Earlier studies have also shown ice-thickening in the upstream areas and thinning on the debris-mantled snout (Kodama and Mae, 1976). Observations from Hambrey et al (2008) suggest that the active zone of Khumbu Glacier has receded even farther in recent decades, to approximately 6 or 7 km from the terminus. Contoured elevation data reveal that the lower most 6 km of the glacier tongue varies in elevation by less than 200 m. Even at the base of the icefall, some 10 km from the glacier terminus and at the transition between debris-covered and clean ice, the average elevation of the glacier surface is only 400 m higher than that of the crest of the terminal moraine.

Tuesday, June 12

Today was our final day of field work on the glacier before we had to make our way back to Lukla. Our objective was to install the base station and resurvey the 9 anchors that we installed three days ago. While spending our last few hours on the glacier I took some time to identify some of the common rocks that we saw and compared my findings with those of Hambrey et al. (2012). From my observations I found that most of the glacier was covered in large boulders to medium to coarse grained sand. The boulders were mostly granite, some gneiss, and occasionally schist. The rocks mostly come from rockfalls, and ice and snow avalanches. The combination of high-relief and rapid tectonic uplift has established debris covered glacier tongues. The Khumbu Glacier receives avalanched debris along its flanks, particularly beneath Nuptse, as opposed to the Imja and the Lhotse Glaciers where the main avalanche fans are derived from the headwalls. Where steep local ice slopes and cliffs are present on the glacier tongue as aresult of differential ablation, continuous debris layers typically half a meter thick are exposed. Debris also becomes entrained in crevasses by falling from the surface (Gulley and Benn, 2007).

The last of the field work went quickly and smoothly and we were on our way to Ding Boche by early afternoon. In Ding Boche Adam installed the charged battery and restarted the turbidity sensor and we left for Thokla where we’d stay for the night. In Thokla we met a Russian trekker travelling alone and headed to Cho La Pass. With him he had brought a Japanese style bamboo flute that he made himself and played very beautifully. We all sat around the stove for about an hour attempting to play the flute, no one could do it, and watching him play. It was a very relaxing evening and our guide said the style of music was very similar sounding to Tibetan flute.

Wednesday, June 13 to Friday, June 15

Wednesday’s objective was to teach one of the employees at the Thokla tea house how to take water samples from the nearby stream and to prepare them for geochemical analysis. Each morning, ideally around the same hour, two 500 mL containers are filled with water from the stream and a photograph is taken of a boulder that marks the water depth of the stream. Then both of the samples are brought back to the tea house where they are labeled and filtered using a hand pump through filter paper. Afterwards the samples are dried and weighed and stored until Adam or Bhairab return to the tea house and collect them.

We’re now on to our last task, charge the last battery and restart the turbidity station in Phakding. We spent Wednesday night in Pang Boche and during one of the mandatory power outages the charger for the battery managed to break. One of the porters was able to contact a friend in Lukla who had a charger that we believed would work for our battery. The plan was to spend Thursday night in Namche Bazar and trek back to Lukla on Friday to charge the battery. After the battery was charged we could then trek back to Phakding to install it and start up the station. Once that was complete we could head back to Lukla and hopefully catch a flight out on Saturday morning.

Saturday, June 16 to Monday, June 18

Saturday was our final day of field work and then we were headed back to Kathmandu for a much needed shower and some pizza (by this time I had been planning my first meal in America for at least a week). As soon as the battery was completely charged we made our way to Phakding and set up the last turbidity station. Afterwards we met up with a couple that lived on a small farm on the river. We were invited in for tea as we waited for their son to arrive so that we could teach him how to properly label and collect 500 mL water samples for more geochemical analysis. Since all that was required was a lesson in labeling we were on our way back to Lukla after having spent less than an hour in Phakding. We made the 14 km round trip in 1 hour and 47 minutes on the way out and 1 hour 32 minutes on the way back. The return trip was quite a challenge since we were trekking so quickly and almost all uphill but we were silently determined to beat our first time. As soon as we entered Lukla we were ready to fill the wait for our flight with replays and highlights from the start of the EUFA 2012 tournament and to do a little relaxing.

Flights out of Lukla to Kathmandu only run in the mornings and the weather had been bad enough that for the past four days there were no flights in or out. We were forced to wait on Sunday as well due to more bad weather which was cutting it close since Adam’s flight back to the US left on Wednesday. Monday morning the weather cleared and we were able to get tickets for one of the smaller airlines. Within a couple of hours of waking up we were on the second flight out of Lukla before the weather could get bad again.

References

Bolch, T., Pieczonka, T., and Benn, D. I. , 2011. Multi-decadal mass loss of glaciers in the Everest area (Nepal Himalaya) derived from stereo imagery, The Cryosphere, 5, 349–358.

Nakawo, M., Iwata, S., Watanabe, O., and Yoshida, M., 1986, Processes which distribute supraglacial debris on the Khumbu Glacier, Nepal Himalaya, Ann. Glac., 8, 129-131.