East Greenland Glaciology

East Greenland Glaciology

Gordon Hamilton and Leigh Stearns

June 22 – July 26, 2005

Recent studies of the Greenland Ice Sheet show that the largest changes are taking place near the ice sheet margins. These changes include an increase in the spatial extent, seasonal duration, and intensity of surface melting, as well as rapid ice sheet thinning in the catchments of several large outlet glaciers. Outlet glacier thinning might be related to an increase in flow speeds due to enhanced lubrication caused by a greater amount of surface meltwater reaching the bed. If this hypothesis is correct, climate change might lead to relatively rapid changes in ice dynamics and ice sheet volume.

We are visiting East Greenland this summer to conduct a program of measurements that will help us understand the processes driving ice sheet change. The field program is related to our NASA-funded study of Arctic glaciers and ice caps using modern satellite imagery. In that study, we use repeat ASTER imagery to map flow velocities of large outlet glaciers, and compare the results with field measurements of velocity made by our Danish collaborators in the 1960s and 1970s to detect changes in flow speed over time.

One of the objectives of this summer’s field program is to revisit many of the original Danish measurement locations and obtain new measurements of velocity using GPS techniques. The results will enable a direct comparison with the archival field measurements and will also be used to validate the results of our remote sensing analysis. We will also visit local ice caps to excavate shallow snow pits to study the frequency of melt events, and to measure snow properties for improving our understanding of features observed in satellite imagery.

Our logistics platform will be the Arctic Sunrise . The trip begins in Isafjordur in northwest Iceland. From there, we will cross the Denmark Strait to the east coast of Greenland. The ship will take us deep into the Scoresbysund fjord system (the largest fjord system on Earth). We plan to access Daugaard Jensen Gletscher, Graah Gletscher and the Renland Ice Cap using the ship’s helicopter. After leaving Scoresbysund, the vessel will sail south along the east coast of Greenland. Ice and weather conditions permitting, we will also conduct measurements on Kangerlussuaq Gletscher and Hellheim Gletscher. We will disembark Arctic Sunrise in the small village of Kulusuk and, from there, fly to Iceland and onward to the United States.

Thursday, June 23, 2005

Reykjavik/Isafjordur, Iceland

Arrived early in the morning at Keflavik, Iceland’s international airport. After collecting all 10 pieces of checked baggage, we boarded a bus for Reykjavik. The 50 km drive took us along the barren volcanic landscape of the Reykjanes peninsula. Our destination was the domestic airport in Reykjavik, but first we were supposed to change to a smaller bus at the central terminal. When we got there, the driver remembered that we had an enormous amount of baggage, so he decided he had better drive us all the way to the airport himself.

We spent the day exploring downtown Reykjavik, before checking in for our late afternoon flight to Isafjordur in northwest Iceland. A bumpy descent through the fjord brought us to the small fishing town, with its single airport taxi. It took a couple of trips, but eventually we transported everything the short distance to the harbor where our home for the next few weeks, Arctic Sunrise, was at berth. We arrived just in time for dinner.

Friday, June 24, 2005

Safjordur, Iceland/At sea, Denmark Strait

After breakfast, we went for a walk through the sleepy downtown of Isafjordur. Not much seemed to be happening, except for a troop of high school kids in reflective vests doing landscaping work by the side of the main road out of town. Actually, most of them were lying down eating chocolate, but it looked like they might be about to start work again. Arctic Sunrise cast off at 12:00 noon and glided slowly out of the protected harbor and into the fjord. Stormy conditions were forecast, but luckily the waves were on our stern so the ship did not pitch and roll too much. We crossed the Arctic Circle about 4:00PM.

Saturday, June 25, 2005

At sea, Denmark Strait

During the night, the ship had to alter course because the edge of the sea ice was enountered in foggy conditions. Rather than attempt to push through the pack in poor visibility, the watch officer chose to sail east along the southern edge until conditions improved. Turning the ship into the swells made for a noticeably rougher ride, but by morning we had resumed our northerly track and the sea had subsided. We continued to sail north east in clouds and wind for the rest of the day.

Sunday, June 26, 2005

At sea, Denmark Strait

We reached the edge of the pack ice just after lunch. We were about 150 miles east of Greenland and about 60 miles north of the entrance to Scoresby Sund, our destination. By entering the pack at this position and sailing west, the ship can take advantage of the south flowing ocean current that opens leads through the ice. Several seals were spotted on ice floes or swimming in front of the ship. There are also thousands of gulliemot chicks out here, presumably having just arrived at their summer feeding grounds. The leads have started to become narrower in the last couple of hours, but forward progress is still good. We expect there will be a lot of bumping and grinding during the night as the ship breaks an occasional channel between leads, but by morning we should have Scoresby Sund in sight.

Monday, June 27, 2005

Leigh writes:

40 miles west of Scoresby Sund, Eastern Greenland

We woke up to our first sunny day! The helicopter had already taken our captain on a scouting trip to find open leads in the water, and we are cruising at 4 knots to Scoresby Sund. Last night we were 40 miles from the entrance of the sound / fjord and today we are still 40 miles from the fjord. The pack ice has been pretty thick, so we had to back-track a bit and approach the fjord from the south instead of the north. The Arctic Sunrise is a relatively small ship and can only break through some ice. As a result, the captain is constantly trying to find leads (pathways with no ice) to navigate through. The ship bounces and jolts quite a bit when it tries to break through ice, and we’ve all had some near falls while walking around the cabins.

After the morning ritual of breakfast and cleaning the ship (everyone, regardless of rank, is assigned a task for the day), I spent most of the day picking coordinates off our Landsat imagery for potential landing spots on the glacier. Either tomorrow or the next day, Gordon and I will fly to Daugaard-Jensen Glacier and start our GPS measurements. We want to measure the ice velocity as close to the glacier front as we can safely get to. We’ll place 3′ conduit pipes at 5 spots across the front of the glacier and measure (with GPS) how fast they move in ~24 hours. Over the past few days, we’ve been preparing our gear, programming the GPS receivers and making sure that the gel-cell batteries are fully charged. We also did basic crevasse rescue exercises in ‘the hold’ (lower deck) of the ship today. It’s possible that some of the crew members and photographers will join us on the ice, so we went over how to get out of crevasses (by hanging from the beams of the ship and prussicking to the rafters. Prussicking is a process in which one climbs up a rope using slings for your body and feet, the slings being attached by slip-knot to the rope). It has really been a beautiful day today. We are within 40 miles of Scoresby Sund, which is the longest fjord in the world. There is sea ice for miles and miles, buttressed by enormous and dramatic mountains. I’ve never been on a ship before, and am really appreciating the slow approach to land. When I’ve been to Antarctica, I step off the plane and am blown away by the spectcular scenery. But on a boat, you are given the details in tiny increments, and you can cherish each one. We’ve seen a number of birds and ringed seals and this morning I saw some HUGE polar bear tracks..but no bear yet.

There are ~20 of us on board right now. There are ~15 crew members (including engineers, cooks, the ‘garbologist, and some volunteers), 2 ‘campaigners’ who work on the Greenpeace logistics and PR, a film-maker, a photographer, a helicopter pilot, a translator (for when we’re in Greenland villages), a website designer (check out www.projectthinice.org), a radio comms guy and us. For now, Gordon and I are the only scientists but others will join in southern and western Greenland. I’m eager to get to the ice, so hopefully tomorrow or the next day, we’ll get to do some science!!

Tuesday, June 28

Scoresby Sund, East Greenland

Excellent ice navigation skills by the ship’s captain brought us through the pack ice choking the mouth of Scoresby Sund early this morning. We followed a lead on the south side of the fjord before the ice clearedcompletely about 25 km from the mouth. We made good progress, skirting past enormous icebergs, and by dinner time we were within 40 km of our first field site, Daugaard Jensen Gletscher. Hugh, the helicopter pilot, and Gordon flew out on a reconnaisance mission during the evening and established a GPS static reference station and an equipment cache on a grassy promontory above the fjord, about 2 km from the glacier’s calving terminus. We saw several muskox families (adults and their young) close to the landing site. We also flew onto the glacier and scouted out potential landing sites. The glacier is extremely crevassed close to the calving terminus, but there are places where it is possible to set down the helicopter and conduct our work safely. Our plan is to fly up to the glacier in the morning and establish the survey lines.

Scoresby Sund is the world’s largest fjord system. Our study glaciers are at the head of the innermost branch, Nordvestfjord, more than 200 km from the coast. Scoresby Sund is also one of the deepest fjords in the world, with depths in excess of 1500 m. Polished rock walls plunge vertically into the water on both sides of the fjord, and numerous waterfalls cascade down the steep cliffs. The icebergs are huge. Several kilometers long in some cases. Each one is unique and a constant source of photographic material for those watching from the ship’s deck. At night, it is difficult to pull ourselves away from the ever changing views and get some sleep.

Wednesday, June 29, 2005

Leigh writes:

Daugaard-Jensen Gletscher

I was speechless and dumbfounded when we entered the northern part of Scoresby Sund. The fog lifted slowly, giving us spectacular views in incremental detail. I can hardly describe our surroundings except to say that it’s the type of adrenaline-inducing landscape that simultaneously makes you want to laugh and do pushups and become a better person. Or maybe that’s just me.

Studying geology shifts your sense of scale. We work in time scales of millions or billions of years; we calculate the forces needed to fold rocks and move tectonic plates; we detect cm-scale thickness changes in ice sheets that are up to 3 km thick. In a similar way, Scoresby Sund altered my sense of scale. Geology features that I’m used to observing in hand samples took up entire fjord walls. Chevron folds, hinge folds, unconformities, fault scarps, boudins, and anticlines of such grandeur I had only seen in textbooks. Moraines deposited from the Last Glacial Maximum ~20,000 years ago; enormous U-shaped valleys and steep-sided fjords; glacial striations, glacial polish, chattermarks, erratics, p-forms – all evidence of the ice that used to blanket the Greenland coast. We were sailing through textbooks of geological processes – geomorphology, glacial geology, structural geology, sedimentology and oceanography – and I could hardly contain my excitement.

Once anchored, Gordon and I made our first trip out to Daugaard-Jensen Gletscher. Having worked with satellite imagery of the glacier for months, I thought that the terrain would feel familiar to me. It was not at all. Unlike the slow-moving interior of West Antarctica, or the smaller glaciers that I’ve worked on in Sweden, Norway, Alaska and Washington, the glacier surface was like a sawtooth blade. Daugaard-Jensen Gletscher is one of the largest and fastest glaciers in Greenland. It drains approximately 4% of the ice sheet and moves ~9 m/day (~3.5 km/yr). When the ice moves faster than it can deform, crevasses form. In this case, the glacier surface was so jagged that it was hard to find places to land our small helicopter.

Setting up our first set of GPS units is a blur to me. We were so filled with adrenaline and purposefulness – so focused on safety and efficiency – that we were exhausted by the end of it. We were constantly double-checking things: for our own safety, for the safety of our (expensive) equipment, and for the value of our data. The less time we spent on the glacier surface, the safer we were. Getting out of the helicopter those first few times, I was focused on three things: crevasses, helicopter blades and the data. Crevasses and GPS data I’m accustomed to worrying about…helicopter blades were another thing. To the constant amusement of Huey (our helicopter pilot), I would crouch and run from those blades even when I was nowhere near them.

The hardest part was locating our stakes to resurvey them. In order to calculate the ice velocity, we need to determine the exact position of the stakes at least 20 hours apart. Even though we knew the GPS coordinate of the pole, they were hard to see on the glacier surface. We attached fluorescent green banners and neon orange flags to them, and still had trouble.

Having surveyed 3 glaciers now, Gordon and I are getting more efficient at setting up and taking down our GPS equipment, and I’m getting more used to the helicopter. We’ve had a number of spectacular days setting up GPS units near perfectly blue meltwater ponds and on seracs overlooking jaw-dropping fjords. Those are the days I’ve archived in my memory for when I’m back in my office in Maine, typing at 4 am.

Wednesday, June 29 – Friday, July 1, 2005

Gordon writes

Nordvestfjord, Scoresby Sund, East Greenland

We are now very close to the head of Nordvestfjord, the innermost branch of the Scoresby Sund fjord system. Daugaard Jensen Gletscher and Graah Gletscher, two of our study sites, are about 10 km away. The ship can’t travel any farther because of a melange of enormous icebergs and sea ice, so we are currently anchored in a protected ice-free bay.

Leigh, Gordon and Hugh began the glacier work after dinner. Fog shrouded most of the inner fjord during the day, but cleared into a spectacular Arctic summer evening. The purpose of the work is to measure velocities very close to the calving fronts of several glaciers using GPS surveys. It involves landing on a crevasse-free platform of ice, drilling in an aluminum stake to serve as a GPS antenna mount, and leave a GPS receiver collecting data. We then fly onto another site and repeat the work. By the time we have installed five sites, we go back to the start and collect the GPS receivers which have recorded for 1-2 hours. We were back on the helideck of the ship by 2:00AM and downloaded our first data from Daugaard Jensen Gletscher.

The trick is finding suitable places for the helicopter to land, and safe enough to work on, among the numerous large crevasses and ice pinnacles. Hughie usually sits nearby with the helicopter running while we work fast to install each site. It takes about 5-10 minutes to drill in each stake and get the GPS receiver running, and only a minute or two to collect the GPS receiver.

On Thursday afternoon, we flew across the glassy calm waters of the fjord to repeat the process on Graah Gletscher. It was more of a challenge finding suitable landing sites here, but we were able to get five markers installed close to the front of the glacier. In the evening, we returned to Daugaard Jensen Gletscher and did a second survey of the markers we had installed the night before. Data from the two GPS surveys conducted a day or so apart allow us to calculate glacier velocities.

Friday’s task was to conduct the second surveys of the markers on Graah Gletscher. We have been very fortunate with the weather, meaning we have been able to fly each day. By lunchtime we were done and the Arctic Sunrise left its anchorage.

Saturday, July 2 – Sunday, July 3, 2005

Gordon writes

Vestfjord, Scoresby Sund, East Greenland

We sailed through the night and woke this morning in another branch of Scoresby Sund, this time Vestfjord. We are here to conduct GPS surveys on Vestfjord Glacier. Hughie and Gordon left on a reconnaissance flight after breakfast. They found the last few kilometers of the fjord full of icebergs and sea ice, but spotted two good anchorages just outside the ice limit. They also flew up to the margin of the glacier and cached some survival equipment and GPS receivers. By the time they returned, the ship was pulling into one of the suggested anchorages.

The installation of markers on Vestfjord Glacier was pretty straightforward. Despite the heavy crevassing, we were able to find good safe landing sites. The markers were drilled in and the GPS receivers surveying in time for us to fly back to the ship for lunch. In the afternoon we flew back to the glacier and collected the receivers.

Sunday morning dawned cloudy and rainy. After breakfast we loaded the GPS receivers back into the helicopter for what turned out to be a very short flight. Hughie gained enough altitude to give us a good view all the way up the fjord which told us that the glacier was fogged in. Thirty seconds after taking off, and a very steep banking turn later, we were back on the helideck. Just in time for brunch! The clouds and fog burned off in the afternoon, so we were able to fly up to the glacier and deploy the GPS receivers for the second surveys. The receivers need to record for at least an hour so that we can calculate accurate differential positions between the glacier markers and our static reference station on the margin. The sun was shining and the pools filled by crystal clear mountain streams were too tempting to resist a quick swim. Yeah, it was cold, but not that cold!

The flight back to the ship was fantastic. Well, at least according to Gordon and Hugh who were sitting in the front seats. Leigh was tightly wedged into the back seat along with all our GPS receivers and survival equipment, and pretty much missed the views of muskoxen, lush south-facing mountain slopes, tumbling waterfalls nourished by the previous night’s rain, glittering icebergs and deep blue fjord water. What goes around, comes around, though — next time Gordon is sitting in the back seat!

The Arctic Sunrise was already sailing by the time we landed in the late afternoon. In warm sunny weather (12 C), we cleaned and re-arranged our equipment on the aft deck of the ship. DInner was eaten on the deck for the first time this cruise. The surrounding mountains and glassy calm fjord provided the perfect setting in which to celebrate the end of another successful glacier survey.

Tuesday, July 5, 2005

Leigh writes

Ittoqqortoormiit

Last night we arrived at Ittoqqortoormiit, a small hunting village at the mouth of Scoresby Sund. From our anchored spot, we could see the dark reds, greens and blues of their houses, and hear the sled dogs barking and whining. In the afternoon we took our life rafts to shore and walked around the village. As soon as we approached land we were bombarded with happy, screaming children all trying to get in our small lifeboat.

Gordon and I spent a few hours walking around the village. Most houses had sled dogs chained out front and meat drying on a rack. It’s a bleak village, even in the dead of summer. Historically they are subsistence hunters, surviving on seal, whale, polar bear, musk ox and fish products. The recent changes in sea ice extent and thickness are directly impacting their hunting patterns and survival. The mayor said that their hunting has decreased by ~50% in the past 5 years and that last year they had to import meat to feed their dogs because there was not enough seal meat.

The majority of the village (pop. 500) came aboard the Arctic Sunrise for a tour later in the day. It was a big event for the town, and many villagers took the lifeboat back and forth a few times. The ship became a huge jungle gym – children were running up and down the deck, climbing ladders and jumping down platforms. A few people spoke English, but for the most part we just smiled at each other. Journalists on board recorded testimonials from people about the impact of global warming on their lifestyles. It was incredibly interesting.

Wednesday, July 6, 2005

Transit

We are now on our way to Zackenberg Research Station, ~250 miles north of Scoresby Sund. The ice is pretty thick, so we are traveling slowly (~ 3 knots). At this rate, we won’t be there for 3 more days. We’ll spend 3 days there, and then we head back south to Kangerlussuaq Gletscher.

It’s difficult to come off four incredible, and incredibly long, days of field work to slow days on the ship. Gordon and I have processed all our GPS data, backed up all of our data and notes, cleaned our equipment and organized it for our next site. Unfortunately we won’t be at our next site for another week or two, so we have created a mini-seminar series for ourselves, where we will read and discuss all the articles in the PARCA (NASA’s Program for Arctic Regional Climate Assessment) ‘Mass Balance of the Greenland Ice Sheet’ journal. So far the seminar has succeeded in keeping us busy and productive. When we’re not doing that, there are always tasks (cleaning, painting, building, repairing) jobs on the ship to do.

Thursday, July 7 – Sunday, July 10, 2005

Gordon writes

Off the coast of NE Greenland

No science at the moment — we are in transit between Ittoqqortoormiit and the Danish Polar Center’s research station at Zackenberg in NE Greenland. In our last update, the ship was making slow progress through the pack ice guarding the entrance to Scoresby Sund. Breaking through ice is noisy (especially when you are trying to sleep), but at least the ice cover dampens the ocean swell. Almost as soon as we cleared the outer limit of the ice early on Thursday morning, we could feel the ship start to roll. For the next 36 hours we experienced the roughest waters of the trip so far. For a couple of land-based glaciologists, I think we came through it pretty well!

The same characteristics of the Arctic Sunrise that make it an excellent ice-class vessel unfortunately also mean that it is very unstable in the open ocean. Icebreakers have rounded hulls that allow them to ride up onto the ice and break it, and the hull is rounded because it has no keel. Now, as anyone who has played with a toy boat in a bathtub will tell you, the purpose of a keel is to provide a ship with some lateral stability. To make up for the rounded hull and lack of keel, icebreakers often carry ballast below the water line to give some stability. Our ballast is fuel and water, but because we have been at sea for a few weeks now, these reserves are providing less and less stability as we go on. Pete, the chief mate, likes to say that the Arctic Sunrise has all the hull stability of an egg!

So, what is it like plowing through 20 foot waves in an egg? Everybody staggers around a lot. Things tend to fly off shelves and tables. Some people lose their appetite (I wonder why?). Eating is an interesting experience — you get a fork full of food just before your plate slides down the table, but hopefully by the time you’ve chewed that mouthful you have your plate back. Or someone’s plate, at least. Just about every normal activity becomes difficult to impossible. Thankfully neither of us have had seasickness. We even managed some fresh air late on Thursday evening — standing at the bow of the ship, watching the waves approach, we had a competition to see who could last the longest balancing on one foot. Leigh won — 24 seconds on one foot as a ship rolls 15 degrees to port and the same amount back again to starboard is pretty impressive. I was just glad not to be flipped overboard!

The rough seas continued through much of Friday until we entered the pack ice again. At that point, we exchanged the rocking and rolling through waves for the loud banging and scraping noises of icebreaking. We have been passing the time processing and analyzing our data from the glaciers we visited last week, and preparing the survey grids for our next set of field sites.

Saturday was notable for one thing: we saw our first polar bear! It was foggy so viewing conditions were not perfect. Still, the site of a large male bear 20 meters away off the starboard side of the ship was very impressive. It looked at us for a while, then seemed to get bored, jumped across a lead between two ice floes and wandered off into the fog. Just as it disappeared, Leigh returned from the bathroom and wondered why everyone was leaning over the side of the ship!

We are still making slow progress through nine tenths ice as I write this on Sunday afternoon. Nine tenths ice means that only 10% of the ocean surface is open water, and a lot of the open patches are disconnected from one another by large floes. Arne, the captain, is piloting the ship from the crows nest, looking for the most efficient path through the close pack. We are averaging 1 knot, or 1.1 statute miles per hour (but a whopping 1.76 km per hour if I think in metric!). Reports indicate that ice concentrations are much less closer to the coast (three tenths ice or better), so hopefully we will pick up speed soon. Meanwhile, Leigh is on the bridge, binoculars scanning the horizon for a polar bear…

Tuesday, July 12, 2005

Leigh writes

Zackenberg Research Station

We’ve spent the past two days in Young Sund, ~200 miles north of Scoresby Sund. We came to visit Zackenberg Research Station, a small Danish station that focuses on the biology and ecology of Northern Greenland. In particular they look at changes in musk ox, plant life, arctic hares, walruses, permafrost, etc. due to a changing climate. The fjord is also home to the Sirius patrol, an elite branch of the Danish military that patrols Greenland (by dog sled) against invaders (mostly Norway, apparently). Twelve guys live at this small station at 74°N for two years at a time. In the winter they spend four months patrolling the northern edge of Greenland, by dog sled. For a remote fjord in Greenland, there was quite a crowd!

Having spent a full week on the ship, traveling 1-3 knots the whole time, Gordon and I were getting restless. The adrenaline rush that we had gotten from doing fieldwork last week seemed like a distant memory. As soon as we had the opportunity to get to land, we planned a long hike around the fjord. Well, we didn’t do so much planning since the only maps we have on board are nautical charts, which don’t have contour lines above sea level. We left at 8:30 pm last night and arranged for a pickup at 11:00 am the next morning.

At around midnight, we reached the top of our first peak, at 1342 m, and instantly missed not having a map! The slope that we hiked up was admittedly steep, but the backside of the mountain was a sheer cliff, all the way down to sea level. From the ship we had no idea that the terrain was so dramatic. We altered our intended route and continued down to the next saddle and up a different ridge.

The landscape was composed of blocks of granite and gneiss, broken apart from repeated freeze and thaw cycles. After hours of jumping and balancing from rock to rock, our ankles and calves were feeling the burn. We headed towards a large snow patch that led to the top of the ridge (snow is a lot easier to walk on than boulders). Apparently, we weren’t the only mammals to take this route. To our surprise, we saw musk ox and polar bear tracks! Once the sea ice breaks out of the fjord (which it already had), bears are rare in the area – especially 1000 m above sea level. But there we were, hovered over day-old polar bear prints, wide-eyed and jittery. We were searching for an adrenaline-inducing adventure, and we got it. For the rest of the trip, every large white rock looked like a polar bear. The sun produced shadows that made the rocks look like they were moving, and it took careful scrutiny to believe otherwise.

We took one 2-hour break at the top of our second peak. We had a spectacular view of the ocean, littered with sea ice in the distance; glaciers with ribbon-like medial moraines draining into a fjord; and steep cliffs in front of us. At 3 am, the sun was still bright and the landscape was lit perfectly. We were both feeling tired, and very fortunate.

The rest of the journey was fun and beautiful, but exhausting. During our epic journey, we traveled 17 miles, and gained ~2500 m in elevation. After 12 hours of hiking, we made it back to the Sirius camp (our pick-up spot) and waited for our ride back to the ship. While we waited, we both took a quick swim in the ice-ridden fjord – a refreshing end to a great day/night.

Wednesday, July 13, 2005

Leigh Writes

In Transit

Another sunny day in Northern Greenland!! We’re on our way to Kangerdlugsuaq to survey our next glacier. It’ll probably take us about a week to get there, since we have to navigate through a fair amount of sea ice first. The exciting news is that today I saw my first polar bear!! There was a mother polar bear with her cub, walking, drinking and playing on the sea ice. They were ~1 mile from the ship, and could really only be seen through binoculars. The captain, who was navigating from the crow’s nest, saw the mother hunting for a seal. Very exciting!!

Later in the day we saw a northern right whale. From a distance it just looked like two black humps, but as it got closer we could see the double blow holes and the characteristic arch behind it’s head. These whales are extremely rare and were almost hunted to extinction.

‘ve been reading about walruses lately; there were supposed to be lots of walruses near Zackenberg Station, but we didn’t see any. There’s something very endearing about their social patterns and big, clumsy appearance. The skin on their necks is over an inch thick, so they can’t turn their heads very well. As a result their red eyes bulge out when they look at something, making them look terrified and awe-struck. They are incredibly social animals, nearly always occurring in groups. The Greenland guidebook says that they are “not afraid of body contact” and will snuggle close to each other to keep warm. In addition they snore very loudly when they sleep. Imagine a whole pile of loudly snoring walruses basking in the sun! Walruses usually eat items from the sea bottom – mostly clams, squid and sea urchin. On occasion they’ll eat seals (by literally hugging them to death!) and rarely, polar bears. Unfortunately, we left walrus-country yesterday so my chances of seeing a heap of snoring walruses on this trip is not likely.

Tuesday, July 19, 2005

Gordon Writes

Denmark Strait

We cleared the edge of the pack ice just after lunch on Thursday, benefitting enormously from the good weather. Hughie was able to fly ahead in the helicopter (affectionately called Tweetie) and pick out a course through the narrow but interconnected leads through the sea ice. After clearing the ice, we turned south to begin the two day transit to the mouth of Kangerdlugssuaq fjord. Iceblink was visible to our west for much of Southward journey (iceblink is the brightening of the horizon — a telltale sign of reflections from sea ice, not open water).

Friday and Saturday were spent out on the open ocean, cruising full speed ahead for the southeast coast. The swells became progressively larger as the day went on and by Saturday morning we were in a Force 8 storm. Most of the swells were on our stern, which means the ship tends to do a lot more yawing than pitching and rolling. The rolling was still to come, though — on Sunday mid-morning, just as Leigh was baking her cinnamon rolls for brunch, Arne, our captain, altered course to begin our westerly track towards the mouth of the fjord. That puts the swells on our starboard beam. For the next eight hours, the ship rolled in exactly the same way you would expect an egg to roll in a bathtub (i.e., a lot, and very frequently)! Because neither of us felt seasick, it was actually quite fun to watch the ship plough through the stormy ocean from the comfort of the bridge. (The cinnamon rolls were a big success, by the way. Much more successful than the quiches which, evidently, do not set if baked on a ship that is moving from side to side!)

We have sighted a few whales. Three dolphins accompanied us for a few minutes on Saturday evening. Arne and I saw a sei whale breach in front of the ship on Sunday morning (did the whale know there is a bumper sticker on the bridge that says “I brake for whales”?). Then a big humpback whale breached very close to the port bow several times later in the afternoon.

We approached the mouth of the fjord on Sunday evening. After being up at 74N for the last week or so, it was quite a change to be “back down south” at 68N. We definitely noticed the difference — there was something approaching a sunset at 12:30AM (the sun really only went behind some mountains, but it made for wonderful views). It was the kind of constantly changing light that kept us out on the bow taking photographs way past our bedtimes!

It is now Monday morning. We are just inside the mouth of fjord, about 65 km from Kangerdlugssuaq Glacier. Hughie and I took off just before 7:00AM and flew up the fjord to navigate a route for the ship through the ice, and to pre-position some equipment up at the glacier. The flight was spectacular. Katabatic wind draining from the ice sheet made for a bumpy ride in Tweetie, but thankfully I had not eaten much breakfast. The biggest surprise of all was that when we got to the glacier, we found that the location of our planned survey grids was no longer on the glacier but in the fjord — the glacier had retreated a few kilometers since our last satellite images were taken in 2002. It seems to have been quite a dramatic retreat. We are now back on the ship, planning new survey grid locations and will fly out to begin the measurements later this afternoon.

Friday, July 22, 2005

Leigh writes

Denmark Strait

It’s been an unbelievable 5 days for Gordon and me. We arrived at the mouth of Kangerdlugssuaq fjord early Monday morning, at which time Gordon and Hughie did a quick fly-over of the glacier. To our surprise, the glacier has changed dramatically since the 2001 satellite image we have been relying on. First of all, it has retreated ~5 km since 2001. Coordinates that we had chosen for our GPS stakes are now well into the water. In addition, there was stranded ice on the ridge walls, ~200’ above the current surface. Kangerdlugssuaq has thinned and retreated much farther than we anticipated.

To document these changes, we ended up doing a much more extensive grid of GPS stakes than we had at any of the other glaciers. We put out 12 poles, and surveyed most of them 4 times (at the other glaciers our grids consisted of 5 poles, surveyed twice). Tuesday night, after a full day of fieldwork, I did some quick calculations of the glacier speed and, to my astonishment, found it was moving 14 km/yr. This is almost triple the speed it was moving in 1996 (6 km/yr). Gordon and I just about fell off our chairs.

We couldn’t believe our results at first. The terminus of Kangerdlugssuaq has been stable since 1962, so we expected the velocity to be relatively consistent as well. Apparently, large changes have taken place since 2001, causing extreme thinning, retreat, and acceleration. Now Kangerdlugssuaq rivals Jakobshaven as the fastest glacier in the world. 14 km/yr. That’s roughly 40 m/day!! In fact, our videographer on board filmed the glacier from his tripod for 2 full hours, and you can actually watch it move!! It’s truly unbelievable.

After Gordon and I checked and rechecked our results, we alerted the crew to our findings and everyone kicked into gear. People were writing press releases, taking pictures, emailing reporters and giving TV and radio interviews. The whole event was totally foreign to us. As scientists, we don’t go about advertising our results this way, but it was very effective – being broadcast in Sweden, Denmark, Germany and Greenland that night.

As for Gordon and me, we plan on heading home tomorrow morning. We have had a terrific trip – in terms of science, scenery, adventure and friendship. Although sad to leave the ship, we are eager to finalize our results and do more research in the lab. The crew was a tremendous help to us and we could not have done it without any of them. A special thanks to Hughie, our helicopter pilot, for his safe landings on spires and straddling crevasses in the middle of one of the fastest glaciers in the world.

Tuesday, July 26, 2005

Gordon writes

Reykjavik, Iceland

The log written by Leigh was supposed to be our last entry from the field. On Saturday morning, when we were expecting to be on a plane heading to Iceland and home, we were back at work on another glacier! Opportunities to carry out fieldwork in this part of the world do not come around very frequently, and because we were so close to Helheim Glacier, another major outlet glacier of the Greenland Ice Sheet, we decided to stay just long enough to check it out and see if anything was happening. Arne, our captain, managed to make very good time on the transit south from Kangerdlugssuaq Glacier and by the early hours of Saturday morning we were entering the mouth of Sermilik fjord. Helheim Glacier lies at the head of the fjord.

Leigh and I stayed up all night, alternating between games of cribbage and watching movies, waiting for the fog to lift so that we could fly with Hughie up to the glacier and take a look. The fog finally lifted at 5:00AM and after three strong cappuccinos we were ready to go. Tweety lifted off into the still morning air and we flew away from the ship, above the glassy fjord waters and massive icebergs, before turning inland and skirting the edge of the ice sheet on our way to the glacier. Leigh had prepared satellite image maps of the glacier as it appeared in the summer of 2001. Imagine our surprise when we flew over the mountains and saw that the glacier, just like Kangerdlugssuaq, had begun a rapid retreat! Right there in the helicopter we decided to stay a few extra days and carry out a measurement program on the glacier. After a quick fuel stop on the ship (for humans and Tweety), we were back in the air at 7:00AM, heading for the glacier to begin our surveys.

Helheim Glacier turned out to be the most challenging of our glaciers to work on. The crevasses were enormous and more chaotic than anything we have seen onthe trip so far. Hughie was incredibly patient in finding safe landing sites — several times we set down on the glacier, before deciding that things were too dicey to risk getting out. Eventually, we were able to find 5 good landing sites at the locations we wanted. One site was our particular favorite – we set up our GPS receiver on a crevasse ridge above the most indescribably beautiful melt pool. Another site was more adrenaline-inducing — because the ice sloped off steeply on either side of a narrow crevasse ridge, Leigh and I had to strap on our crampons before venturing away from the helicopter. Just like the other glaciers we have worked on, the weather was perfect once again, so that definitely helped.

We repeated the surveys on Sunday morning. Leigh and I processed the data as soon as we got back to the ship — to our amazement, Helheim Glacier has also accelerated in recent years. Leigh clocked the glacier’s speed at a respectable 8 km/yr in 2001, using sequential satellite images. But now, the glacier is trucking along at nearly 11.5 km/yr, an almost 40% increase in speed. Clearly, the changes we observed on Kangerdlugssuaq Glacier are not restricted to one glacier in Greenland. The results will give us plenty to work on when we get to Maine.

Tweety needed some maintenance, so most of the remainder of Sunday was taken up with Hughie and a visiting Icelandic mechanic doing repairs to the rotor blades. Leigh and I spent the downtime hiking the mountain ridge above the ship’s anchorage. The views from the top were fantastic — ice chocked fjords, sparkling skies, steep mountains everywhere. Glaciologists certainly have to put up with their fair share of bitter cold and discomforts, but days like this make me realize that I have the best job in the world. No question. And speaking of ice choked fjords — Leigh and I swam in one after we descended from the mountain 🙂

After a few hours sleep, we were up again and flying to the glacier at 4:00AM on Monday morning. We had just enough time to do another survey of our markers, measure the depths of some melt pools (using an ingenious device consisting of a calibrated rope weighted with a shackle that we dangled out the door of Tweety while Hughie hovered us close to the surface of the pools – our Lake-o-meter). We returned to the ship with all our equipment and spent a somewhat frantic hour packing everything and saying goodbyes before Hughie flew us to Kulusuk airport and our flight to Iceland. It was very sad leaving the Arctic Sunrise — Leigh and I truly had the time of our lives. Every crew member contributed to the success of our project and we are tremendously grateful to them all — I know that many lasting friendships have been formed.

So, a few hours after being on a fast moving glacier in East Greenland, Leigh and I found ourselves in the relatively sumptuous surroundings of a Reykjavik hotel. First order of business was a hot shower. A long hot shower to make up for all the 2 minute ship showers we have taken the past month. And after that, a nice green salad! Tomorrow evening we will be back in Maine, back where the adventure began.

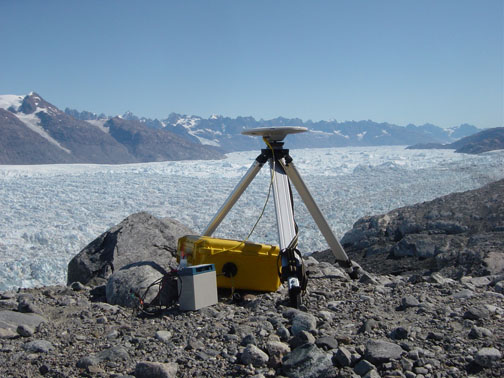

- 19th July 2005 – Kangerdlussuaq Glacier, EAST GREENLAND Gordon Hamilton, glaciologist from the University of Maine ( USA) sets up monitoring equipment on the remote Kangerdlussuaq Glacier in Greenland to measure the rate at which the glacier is moving. Initial results would suggest a rate of flow much larger than expected and could make the glacier one of the fastest moving in the world © Greenpeace/Steve Morgan GREENPEACE HANDOUT – NO ARCHIVE – NO RESALE – OK FOR ONLINE REPRO